EcoTipping Points

- How do they work?

- Leveraging vicious

cycles to virtuous - Ingredients for success

- Create your own

EcoTipping Points!

Stories by Region

- USA-Canada

- Latin America

- Europe

- Middle East

- South Asia

- Southeast Asia

- East Asia

- Africa

- Oceania-Australia

Stories by Topic

- Agriculture

- Business

- Education

- Energy

- Fisheries

- Forests

- Public Health

- Urban Ecosystems

- Water and Watersheds

Short Videos

- Saving a Coral Reef and Fishery (Apo Island, Philippines)

- Community Gardens Reverse Urban Decay (NYC, USA)

- Community Forests Reverse Tropical Deforestation (Thailand)

- Escaping the Pesticide Trap (India)

- Rainwater Harvesting and Groundwater Replenishment (Rajasthan, India)

How Success Works:

- Saving a Coral Reef and Fishery (Apo Island, Philippines)

- Community Gardens Reverse Urban Decay (NYC, USA)

- Community Forests Reverse Tropical Deforestation (Thailand)

- Escaping the Pesticide Trap (India)

- Rainwater Harvesting and Groundwater Replenishment (Rajasthan, India)

Human Ecology:

Principles underlying

EcoTipping Points

Mexico - Quintana Roo - Sustainable Agro-forestry in the Zona Maya

- Author: David Nuñez

- Posted: May 2009

- Site visit assistance and editorial contributions: Gerry Marten

After decades of being denied lumber-rights, communities deep in the jungles of the Mexican State of Quintana Roo have rediscovered what it means to be stewards of the land. In reclaiming their rights, they have also learned to take responsibility for preserving the forest and diversifying their economy. By establishing permanent forest zones, organizing local forest management authorities, and promoting community forest enterprises, deforestation trends have been reversed and the region has become a model of sustainable forest management.

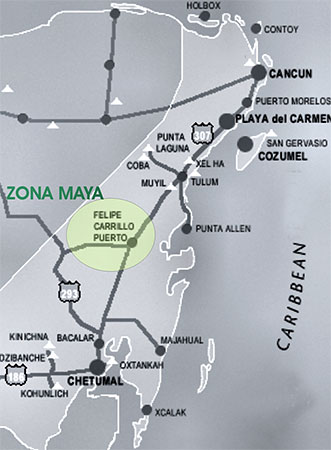

Several hours south and inland from the Mexican Caribbean beach resort destinations of Cancun and Playa del Carmen in the Mexican State of Quintana Roo, we enter the Mayan Zone. Far from the white sand beaches and crowds of tourists, this remote jungle region is where the native Maya retreated to from the onslaught of invaders- first from the Spaniards during colonization, and later from the Mexican army, which didn’t gain control of the region until 1901. The last skirmishes were fought near the city of Chan Santa Cruz, which was quickly renamed as Felipe Carrillo Puerto in an attempt to erase its cultural and historical significance to the native Maya.

Entrenched for centuries, Maya culture has resisted such efforts and Felipe Carrillo Puerto is still the unofficial religious and cultural capital of the Quintana Roo Maya, as is evident to even the most casual visitor in the language, food and costumes. It is also the proud home of a school of traditional Maya medicine. But perhaps the most striking difference one notices upon spending time here, is a true sense of community- so absent from the resort towns, and reflected in numerous non-profit groups- traditional dance and music ensembles, arts & crafts cooperatives, women’s groups and other such organizations- that celebrate and preserve their proud heritage.

When one ventures out of the city and into surrounding villages, one is struck not just by the savage beauty of the jungle, but by the simple stick huts- one room shacks- that so many families still live in, the dense forest only a few feet away, merging seamlessly with the family’s garden where dozens- or even hundreds- of weeds, shrubs and trees offer up their seeds, leaves, roots & fruits as food & medicine. “I may not have much money,” says Don Emiliano with a wide grin as he proudly shows us around his house, pointing out the uses of this and that plant, “but I don’t go hungry”.

We are in the X-pichil ejido, about half an hour east of the city. Ejidos are communal lands which have been redistributed (along with regulations for their management) by the federal government, mostly to indigenous communities, as a result of the land reforms which followed the Mexican revolution of the early 20th century. Though ejidos are communally owned lands, for most of the 20th Century the Federal Government claimed ownership of forest resources and offered concession rights to state-owned forestry enterprises, also run by the federal government. In the state of Quintana Roo, the timber company Maderas Industriales de Quintana Roo (or MIQROO) held exclusive harvesting rights to all ejido and federal lands, and benefited from both subsidies and price controls for nearly three decades, ending in the early 1980s. Under this system, deforestation was encouraged as government controls kept lumber prices artificially low and local people were prevented from participating in the marketing of the forest products they harvested. In the absence of any incentives for proper forest management, most ejidos (which by the way own over half of all forest lands in Mexico) opted for clearing the land for agriculture, while selling the surplus lumber. Reforms in the 1980s and 90s did away with most state-owned enterprises (except for those in the Energy Sector), and encouraged the formation of independent producer sub-groups within the communal ejido structure.

Don Emiliano is such a producer, and he showed us how he and his fellow ejidatarios are transitioning from unsustainable shifting agriculture of annual crops, to a more sustainable model of agroforestry with fruit trees, timber plantations, chicle gum extraction, and honey production from the melipona native stingless bee. The X-pichil ejido was initially reluctant to adopt this model, and only did so several years after neighboring ejidos were successful in doing so. “We were stupid,” Don Emiliano says wistfully. “If we had paid more attention to the ingenieros earlier, when they first began to talk to us, we would be much further along by now.”

The Eco Tipping Point in this story came when local ejidatarios throughout the Zona Maya decided to stop dealing with the old lumber company which continued to pay a fixed price for lumber regardless of quality or quantity, and instead seek out a fair market price for their products. In doing so, they had to learn about the lumber market, but also about proper forest management.

To help them do so, the National Forestry Commision launched a three-year Forestry Pilot Program with six ejido communities in 1983. In accordance with the Forestry Pilot Program strategy, the general assembly of each ejido was:

- Required to establish Permanent Forest Areas, which restricted the lands available to agriculture and lay the foundation for long-term management plans.

- Trained to implement its own Forest Management Authority, so that the community assumed all responsibility for management, harvest and sale of all forest products (timber and non-timber).

- Encouraged to develop Community Forest Enterprises, empowering the locals to market their various products.

But perhaps the key to the Program’s enduring success decades after it officially ended, lay in the fact that it also helped launch independent umbrella organizations to increase the collective bargaining power of ejidos, offer technical assistance, and continue all these efforts once the Pilot Program´s three-year run was over.

Our graceful guide on this journey, Rosa Ledesma, is an agronomist with one such organization, the Organizacion de Ejidos Productores Forestales de la Zona Maya, which was founded in 1986 – the last year of the Forestry Pilot Program - and represents 22 ejidos. Four such organizations now represent at least 42 different ejidos, while another 14 ejidos have independently developed similar projects their own.

The new timber marketing strategies proved so successful that locals soon began to market other products, such as the leaves of the guano palm and various grasses for the construction of thatch roofs. And these empowered communities soon started organizing in other ways, such as Women’s Artisan Cooperatives and, more recently, ecotourism ventures.

Several of these Community Forest Enterprises have now been certified by the Forestry Stewardship Council, (www.fsc.org) though locals argue that they have yet to see any benefits of certification, as the Mexican lumber market has yet to respond to certification incentives. In a sense these communities which were once considered “backward” enough to require federal intervention, are now leading the way and waiting for the rest of the country to catch up.

Under a poor policy scheme where trees were not properly valued, they were considered little more than waste to be cleared to make way for subsistence agriculture of annual crops, which because of the poor soils of the region was constantly shifted to newly deforested lands. As soon as fair prices began to be offered- or rather, demanded- for timber, Permanent Forest Zones were immediately established to limit agricultural areas. People began experimenting with deep tilling as a means of “fixing” their cornfields, and diversified their crops by adding fruit trees- such as citrus, mango and guava- that do not need to be replanted yearly. Timber plantations followed, and now producers can count on a great variety of crops, some for immediate use (corn, beans, squash & peppers), some which take a few years to begin to pay-off (fruit trees, polewoods), and others which are more of a long-term investment (cedar & mahogany).

Chicozapote tree with scars from the chicle gum harvest

This diversification of the economy has allowed more of the younger generation to go to school. Though patio gardens and orchards may have kept families from starving, they didn’t offer many opportunities beyond that. With disposable income, come new horizons- as well as new hazards. Don Emiliano admits to us that he foolishly drank away the profits from his first sale of timber years ago, but quickly points out that his children are not that dumb. They finished high-school. They’ll do better.

Though outside stimulation was necessary in the form of a federal government pilot program, which in turn was sponsored by the German government, the strong democratic traditions of ejido management allowed the spirit of self-reliance, so fundamental to long-term success, to flourish once it was given a chance. In fact the main reason for the program was to reverse the damage done by decades of bad policy that had also been imposed from the outside.

Everything changed once these communities were allowed to market their own timber. As soon as their long-denied rights to the natural resources on their land were restored, the ejidatarios’ collective ancestral memory of natural resource management kicked in, as is evident in the number and variety of projects that sprung in parallel to timber management: guano palm & grasses were marketed for thatch roof construction at the tourist resorts; chicle gum- which was the original crop and the reason many of these ejidos were formed in the first place- was rediscovered; production of honey from the stingless melipona bee became popular again. In brief, nature’s bounty once again flowed through communities that had been, at least partially, cut off from it.

What started out as a pilot effort with 6 communities now includes over forty ejidos organized in four different producer’s cooperatives throughout the Zona Maya and in other parts of Quintana Roo. In the Zona Maya deforestation has slowed to nearly imperceptible rates since the 1990s, and forest cover has in fact increased by at least 10 percent. By returning resource control to communities, these were able to change their environmental future and become models of sustainability.

References

- The Institutional Drivers of Sustainable Landscapes: a Case Study of the ‘Mayan Zone’ in Quintana Roo, Mexico, Bray, et al., Land Use Policy, 21 (2004) 333-346

- The Mexican Model of Community Forest Management: the role of Agrarian Policy, Forest Policy, and Entrepreneurial Organization, Bray, et al., Forest Policy and Economics, 8 (2006) 470-484

- Mexico’s Community Managed Forests as a Global Model for Sustainable Landscapes, Bray, et al., Conservation Biology, Vol. 17 No. 3, June 2003, 672-677

- Community Forest Enterprises as Entrepreneurial Firms: Economic and Institutional Perspectives from Mexico, Antinori & Bray, World Development, Vol. 33 No. 9, (2005), 1529-1543

- Estrategias de Recuperación de Selva en dos Ejidos de Quintana Roo, México, Rebollar, et al., Maderas y Bosques, 8 (1), 2002, 19-38

- Tropica Rural Latinoamericana website (Mayan forest managed by the people, for the people) [www.tropicarural.org]