EcoTipping Points

- How do they work?

- Leveraging vicious

cycles to virtuous - Ingredients for success

- Create your own

EcoTipping Points!

Stories by Region

- USA-Canada

- Latin America

- Europe

- Middle East

- South Asia

- Southeast Asia

- East Asia

- Africa

- Oceania-Australia

Stories by Topic

- Agriculture

- Business

- Education

- Energy

- Fisheries

- Forests

- Public Health

- Urban Ecosystems

- Water and Watersheds

Short Videos

- Saving a Coral Reef and Fishery (Apo Island, Philippines)

- Community Gardens Reverse Urban Decay (NYC, USA)

- Community Forests Reverse Tropical Deforestation (Thailand)

- Escaping the Pesticide Trap (India)

- Rainwater Harvesting and Groundwater Replenishment (Rajasthan, India)

How Success Works:

- Saving a Coral Reef and Fishery (Apo Island, Philippines)

- Community Gardens Reverse Urban Decay (NYC, USA)

- Community Forests Reverse Tropical Deforestation (Thailand)

- Escaping the Pesticide Trap (India)

- Rainwater Harvesting and Groundwater Replenishment (Rajasthan, India)

Human Ecology:

Principles underlying

EcoTipping Points

USA - Hawaii - Restoring the Life of the Land: Taro Patches in Hawai'i

- Author: Regina Gregory

- Special thanks: Sharon Spencer, Penny Levin, Eric Enos, Lolana Fenstemacher

- Posted: August 2014

Cultivation of taro, the staple crop from which poi is made, declined precipitously in Hawai'i over the last century. The art of doing so was almost lost. Renewed interest began with the "Hawaiian Renaissance" of the 1970s, but progress was slow until the 1990s, when a statewide network dedicated to taro patch restoration was created. Besides being a local food source, taro patches are oases of Hawaiian culture and connection to the land.

For thousands of years taro has been a staple crop throughout the Pacific Islands. It is like rice in Asia or corn in the Americas. The stories of taro's origin probably vary across the region, but in Hawai'i the consensus is this: The first taro (kalo) sprang from the grave of a stillborn child—named Haloanakalaukapalili—of the god Wākea and his daughter Ho'ohokukalani. Their second child, Haloa, was the first man. So taro is the elder brother of man, and this kinship is never forgotten.

With the basic philosophy of working with nature to create abundance, Hawaiians developed "the highest level of technology and intensity of cultivation of the crop on earth" (Onwueme 1999). The "technology" involves no machinery, but a carefully calibrated gravity-fed irrigation system.

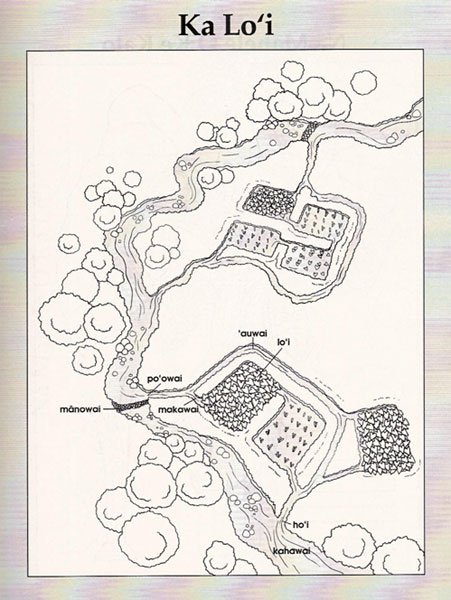

Typical taro patch system

Source: Welina Manoa (http://welinamanoa.org/ka-papa-loi-o-kanewai-1/na-mahele-o-ka-lo%ca%bbi/)

As one can see in the diagram, the river (kahawai) is slowed by a loose wall of rocks (manowai). Not a dam that creates a lake, but just slow enough so some of the water flows into the headwater (po'owai) and down the rock-lined canal ('auwai). The water flows into each lo'i (taro patch) at its upper corner and out into the next patch from its lower corner. Eventually the water is returned (ho'i) to the stream. The flowing water keeps the taro roots at a suitably cool temperature, which is essential in preventing rot. As an added benefit, the lo'i also act as sedimentation ponds; water going out is often cleaner than when it went in.

Over the centuries, lo'i filled every valley in Hawai'i. Where soil and water were not suitable, dryland taro was grown. All accounts of the white men who first travelled to Hawai'i in the late 1700s marvel at the abundance of the land (which included not only intensive agriculture but also aquaculture in coastal fishponds as well).

Those white men proved fatal to the whole Hawaiian way of life. Their diseases caused a precipitous decline in population. Their sugar cane plantations stole the water. The changing economy drew people away from farming. Taro cultivation fell from 20,000-30,000 acres in the 1880s to only 400-500 acres today. The irrigation systems and taro patches were abandoned and became overgrown by forest. But they remain, waiting to be found.

The 1970s (not coincidentally the time of race riots and the American Indian Movement as well as the environmental movement in America) saw the "Hawaiian Renaissance," a time of renewed pride in Hawaiian identity and interest in Hawaiian culture, language and subsistence. This included taro patch restoration. Luckily, the energized youth connected with the elders whose knowledge of the old ways was in danger of being lost. The benefits are many:

Food. Once self-sufficient, Hawai'i now imports nearly 90% of its food. Growing more taro improves food security and the local economy. As a staple crop, taro is actually superior to rice or corn because the broad green leaves as well as the roots are delicious and nutritious, high in vitamins and minerals. Imagine a large fortified potato with kale growing on top.

Culture. Taro patches are known as "cultural kipuka." A kipuka is a little hill that escapes the scorching lava flow around it. It serves as a source of seeds for when the land cools down and can regenerate. Taro patches are kipuka for Hawaiian culture. Here the youth can connect to the land, and learn and practice the ways of their elders. Hawaiian values come to life: aloha 'āina (love the land), malama 'āina (take care of the land), laulima (work together), kōkua (help without being asked), and, of course, the responsibility of taking care of the elder brother Haloa. Nothing connects a person to the earth quite so effectively as standing knee-deep in the squishy mud of a taro patch. And few things are so satisfying as looking back at the results of a communal effort.

Biodiversity. Taro patches are also kipuka for taro varieties that have become rare over the years (the number of cultivars has fallen from an estimated 200-300 to just 80-90). In some areas, taro patches are also home to endangered waterfowl.

Education and rehabilitation. For pre-school all the way up to college, taro patches offer educational opportunity. Some Hawaiian charter schools have weekly visits to a taro patch as part of the curriculum. Besides history and culture, students learn about agriculture and natural sciences. Moreover, working in the taro patches has proven to be effective as rehabilitation for "troubled" youth, drug addicts, and ex-convicts.

Wild Youth and Wise Uncles

Ka'ala

Known as the "bad" side of the island in terms of social problems, the district of Wai'anae on O'ahu was targeted in the 1970s by the U.S. War on Poverty's "Model Cities" program. One of the projects was the Wai'anae Rap Center for alienated youth. A local non-profit leased 97 acres of former ranch land in Wai'anae Valley from the state for "youth development" and sent the youth camping there. In 1976 they noticed a widespread series of rock terraces in the valley. After a little research, the youth recognized it as an ancient taro system, 300-600 years old. They decided to set about restoring it. According to participant Eric Enos, "we were just angry and trying to figure out what we were going to do … but trying to take that anger and turn it into something positive." The youth enlisted the help of local kupuna (elders), as well as Uncle Eddie Ka'anana from the Big Island, who were raised in the old Hawaiian ways. Besides being technical experts, "the uncles were grounding elements," says Enos (Pang 2006). Reconnecting with the land, and the goal of creating a "parallel economic and cultural system," gave their lives new meaning (Cultural Learning Center at Ka'ala n.d.).

With a good deal of laulima (communal work), a portion of Wai'anae Valley's taro patches was restored—perhaps 3 acres of the 250 that once existed, according to Enos. Original plans called for taking water from an old plantation ditch, but instead the lo'i are fed by a 1-mile, 2-inch water pipe from Honua Stream. In the non-irrigated area, there are dryland taro gardens and other traditional plants such as wauke (mulberry). A traditional hale (house) was also built.

Lo'i at Cultural Learning Center at Ka'ala

Source: kaala.org

The project blossomed into the Cultural Learning Center at Ka'ala (a.k.a. Ka'ala Farm), named after the nearby Mount Ka'ala, the highest point on the island of O'ahu. The local elders and Uncle Eddie were the teachers. According to taro farmer Penny Levin, Uncle Eddie "brought back the art of making poi pounders and boards and taught them all to pound poi, at a time when no one on O'ahu was still practicing it. He and Walter [Paulo] also taught the Ka'ala gang not only how to build a traditional fishing canoe but also how to use it. Uncle Eddie also taught Ka'ala and Kanewai the art of building hale pili (grass-thatched house)." His teachings inspired many young people, among them Daniel Anthony and Daniel Bishop, who went on to restore lo'i on the windward side of O'ahu. Uncle Eddie also helped restore the taro patches at Ānuenue Elementary School in Palolo Valley.

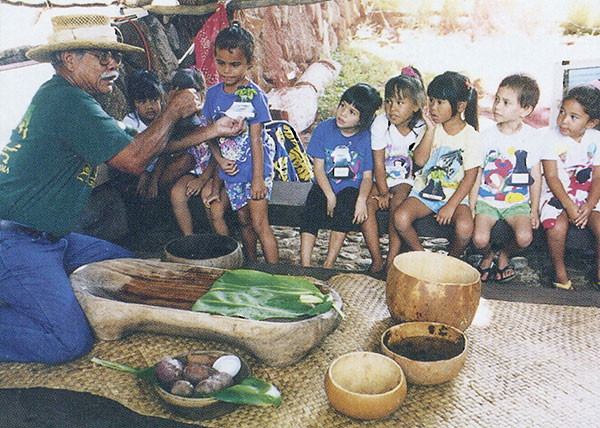

Uncle Eddie and the keiki (children)

Source: Cultural Learning Center at Ka'ala. n.d.

Today, Ka'ala Farm hosts about 3,000 elementary and intermediate school students per year. The highest concentration is 4th graders, because in the Hawai'i Department of Education, that is the year to learn about "place." The students learn about the place and the old ahupua'a (watershed) land-and-water management system. They plant, weed, harvest, and eat the taro. They learn other useful skills as well, like making poi, kapa (barkcloth), and woven mats. Ka'ala also offers the setting for an interdisciplinary high school curriculum in conjunction with the Hawaiian Studies Center at Wai'anae High School. Students learn about archeology, natural resource management, geology, biology, hydrology, agriculture, etc. all in this outdoor classroom. The hands-on learning is far more effective than reading books, especially for the native Hawaiian students. But the main point, according to co-founder and now Executive Director Eric Enos, is teaching values. The Center's motto is this: "If you plan for a year, plant kalo. If you plan for ten years, plant koa (Acacia tree). If you plan for one hundred years, teach the children—Aloha 'Āina (love of the land)."

Besides high-quality, hands-on, place-based education and free labor, this is a great way to disseminate taro. According to Ka'ala Farm's booklet on kalo basics (Enos & Johnson 1996),

To encourage the children to plant and eat kalo we often give them huli kalo (cuttings from taro shoots) to plant at home; the instructions we give them show them how to plant it in the ground or in pots for those children who live in apartments or have very limited backyard space. (preface; emphasis original)

Students working in the lo'i at Ka'ala Farm

Source: kaala.org

Ka'ala Farm also serves as a work therapy site for people in local substance abuse treatment programs, and a community service site for those who need community service hours, or who just want to volunteer.

Kānewai

The little area of Honolulu called Kānewai gets its name from a spring created there by the god Kāne when he first came to O'ahu. The water is said to have healing powers.

In 1980, some members of the Hawaiian language and culture club "Hui Aloha 'Āina Tuahine" at the University of Hawai'i were walking along Mānoa Stream when they discovered a rock-lined canal running parallel to the stream. Further investigation revealed a complete lo'i system right across the street from the university campus. Their research showed this taro patch is over 500 years old. The entire valley was once in kalo, and the area was famous for its taro. The site had been under cultivation by taro farmers as recently as 1968, when the university evicted them to make way for new dormitories. Those dormitories were never built.

The students established a project called Ho'okahe Wai Ho'oulu 'Āina, which means make the water flow, make the land productive. They formed a non-profit corporation and received a grant of about $50,000 from the state Legislature. They enlisted the help of Uncle Harry Mitchell from Maui to restore the lo'i and named their garden Ka Papa Lo'i o Kānewai (the taro patch of Kānewai). Through the generosity of old-time taro farmers, the assembled the most complete Hawaiian taro collection in the state, according to co-founder Lolana Fenstemacher. They also planted fruit trees and native plants and built a hale. The lush green oasis in the heart of urban Honolulu became a favorite gathering place for young people interested in reviving Hawaiian culture. They dug an imu (underground oven) which is still used for cooking communal meals.

Uncle Harry and the UH students

Source: Welina Manoa

Mānoa Stream and the headwater of Kānewai's canal

Photo: Malia Gregory

In the mid-1980s oversight of the garden came under the UH School of Hawaiian, Asian, and Pacific Studies. It received little funding, but flourished with the help of volunteer labor. Community workdays have been on the first Saturday of every month ever since 1980. In the late 1980s a conflict arose because, somewhat ironically, construction of the new Center for Hawaiian Studies destroyed some of the lo'i as well as the spring. Most egregious, according to Fenstemacher, was the destruction of some rare cultivars.

The Center for Hawaiian Studies has since become part of Hawai'inuiākea School of Hawaiian Knowledge, and so has Ka Papa Lo'i o Kānewai (the other departments are Hawaiian Language and Native Hawaiian Student Services). Ka Papa Lo'i o Kānewai is now the perfect location for Hawaiian Studies classes on growing taro (e.g. HWST 351 and 352). Its 17 lo'i are currently home to about 63 different taro varieties. They are grown organically, with leaves for fertilizer and—until recently—two fat white ducks as pest control (ducks eat snails).

Ka Papa Lo'i o Kānewai

Photo: Diane Groves

Like Ka'ala Farm, Ka Papa Lo'i o Kānewai hosts hordes of schoolchildren. Altogether an estimated 15,000 people of all ages visit every year. With the help of a federal grant, a Cultural Resource Center has just been completed where the old shed used to be.

In 2003, in cooperation with Kamehameha Schools, a "sister site" was established in Punalu'u, on the opposite side of the island of O'ahu. Community workdays there are on the third Saturday of each month. Volunteers and students currently total about 3,000 per year at Punalu'u.

'Onipa'a Nā Hui Kalo

Literally "steadfast the taro groups," 'Onipa'a Nā Hui Kalo (ONHK) has its roots in the early 1990s with a small group of taro farmers who exchanged huli (taro shoots), information, ideas and experiences and thought about how to bring kalo back to the land. They assisted when the Windward O'ahu office of Queen Lili'uokalani Children's Center (QLCC, a trust created by the queen to help orphaned and destitute children) decided to try lo'i restoration as a community organizing project. They called a workday at the farm of a Mr. Chaney in Waialua, on the north shore of O'ahu. The workday really struck a chord with the community and was very successful. Hui Kalo o Waialua (taro group of Waialua) was formed to continue with the work of restoring lo'i in Waialua.

Not long after the Waialua workday, a people's water conference occurred in Waiahole Valley (O'ahu) at what would later be known as the Mauka Lo'i. Nearly 200 people restored taro patches there. That was another big catalyzing event in the formation of ONHK and its purpose. In summer 1997 the group restored taro patches in Halawa Valley on the island of Moloka'i.

In November 1997, an important meeting took place at the Windward Unit of QLCC. According to Gwen Kim (1999), "Kalo farmers from the ahupua'a (watersheds) of Halawa and Kahana, to the flatlands of Waialua to Ke'anae came to kūkākūkā (discuss)," along with people from the College of Tropical Agriculture, local residents, and QLCC staff. 'Onipa'a Nā Hui Kalo officially got its name ('onipa'a was one of Queen Lili'uokalani's mottos), and taro became the key community-building initiative of the Windward Unit. It is thought that "By participating in cultural learning experiences via lo'i kalo and 'auwai restoration, orphan and destitute Hawaiian children and their families will develop positive identity and self esteem" (Spencer 6/23/14).

ONHK has grown to a statewide network of more than 300 taro farmers and their allies who, together with community members, gather for lo'i restoration work around the state. With a new set of youth (including QLCC beneficiaries and Hawaiian charter school students) and a new set of uncles (including the brothers Reppun and Daniel Bishop), plus many communities interested in taro patch restoration, over the last 18 years ONHK has restored taro patches on all the major islands, including:

Moloka'i

- Halawa Valley

Hawai'i Island

- Kohala

- Iole

- Waipi'o

O'ahu

- Waialua

- Waipao

- Waiahole

- Maunawili

- Kalauao

- Aihualama (See Video [link: http://vimeo.com/14514275 ])

- Kahana

- Punalu'u

Maui

- Wailua Nui

- Waihe'e

- Waikapu

- Olowalu

- Kauaula

- Iao

Kaua'i

- Ke'e

- Anahola

- Huleia

- Ha'ena

Newly restored mile-long 'auwai on Kaua'i

Photo: Sharon Spencer

Lo'i restoration work in Iao Valley, Maui

Photo: Sharon Spencer

Newly planted lo'i at Waipao, O'ahu

Photo: Sharon Spencer

It is amazing what a workforce of 200-300 can accomplish. It is the perfect example of laulima (working together). As described by one youngster at Waipao in 2007, "Aunty, first they had a forest, and they cut it down … and we planted kalo … all in one day. It was awesome" (Spencer 2008).

But such an awesome day of transformation requires a good deal of planning and preparation. QLCC's Sharon Spencer explains the process:

Requestors come in the January meeting and 4 or 5 requests to restore a site are made at that meeting. I organize a reconnaissance group to visit the 4 or 5 sites. Uncle Paul, Uncle Charlie, Uncle Danny, Alapaki Luke, Matuu (Queen Lili'uokalani Children's Center co-lead) and a few invited ONHK members from that island. We are now trying to get the younger generation interested in learning the process so I consult with the Uncles who they think will be suitable. When we have the members I notify them of the date that the reconnaissance will be. I pay for tickets and we fly up or travel to the sites. We look at the site. The Uncles take pictures, etc. The questions that we ask are pertinent to whether we are going to do a workday or not. At that time we also look for a place to camp should we OK the workday.

Questions:

Who owns the land/ lo'i?

Where is the source of water?

What is the name of this lo'i, 'auwai, etc.?

What is the history of this lo'i /land?

Who will participate from the community?

Who is going to maintain the lo'i?

Do you know of anyone who might oppose ONHK coming to restore this lo'i?The Uncles then make a laundry list of things that need to be done before I can schedule a workday. This might include:

Rebuild banks

Update maps

Purchase pipes- 8" or 6 "

Find out the water source

Talk to family about it and get a letter from each member saying they do not oppose

Get someone who knows the history of the land, lo'i, etc.

Get permission letter from landownerWhatever the issue is, we ask that they address it before any planning. The road needs to be smooth.

If the road is clear—meaning there do not seem to be any roadblocks to restoring the lo'i—I will then work with the landowner or leasee on the following:

Date?

Who will cook?

Where will ONHK camp?

Is there a shower/ toilets?

Financial support?

My role and the lessee's role?

Flyer?At the next ONHK meeting, I will detail the various requests for a workday and then ONHK gets to vote on the workday for that year. We have done 1 and sometimes we have done 4 in 1 year. If it is on O'ahu we usually have the ability to do more.

Once ONHK votes on the workday, I request a flyer to be completed and I post it to ONHK mailing list (300). I usually get about 30 to 40 interested individuals.

Dr. Kalama Niheu comes as the ONHK kauka (doctor)

Reppun brothers- Charlie, Paul and David are the engineers for bringing in water

Alapaki Luke and his gang are experts in lo'i work and safety issues

Uncle Danny is head safety officerWe encourage 'ōpio (youth) and keiki (children) to be brought to projects and workdays. Aunty Leialoha always brings 'ōpio – these youth are lo'i experts and young mahi'ai (farmers). Aunty Lehua brings her families and kupuna.

I arrange the following with requestors and ONHK members:

Food preparation, menu

Camping- showers, toilets, tents, ez corners, amenities

Porta potties

Flights or travel arrangements

Early team arrangements

Huli (taro shoots) (who is bringing)

Concerns—order supplies, pack supplies, barge tools if needed, arrange for pick-up of barged items.

Correct forms are completed—Queen Lili'uokalani Children's Center Lo'i forms and water forms, Queen Lili'uokalani Children's Center insurance form.At the workday when we arrive- the site is already set up as I sent up an early crew.

The workday "is where all the magic happens," says Spencer. "It's the connection to the 'aina (land) and ancestors."

Educational Resources

School curriculum – A year of activity and discussion for grades 6 through 12. Available online at http://kupunakalo.com/index.php/site/curriculum

A Handbook of Kalo Basics for its planting, care, preparation & eating by Eric Enos and Kersten Johnson. 1996. Available from Cultural Learning Center at Ka'ala, P.O. Box 630, Wai'anae, HI 96792. Phone (808) 696-4054.

Guidelines for Grassroots Lo'i Kalo Rehabilitation: Pono, Practical Procedures for Lo'i Kalo Restoration. 'Onipa'a Nā Hui Kalo 2004. Available from your nearest QLCC office (see qlcc.org for contact information).

References

Cultural Learning Center at Ka'ala. n.d. Brochure.

Enos, Eric and Kersten Johnson. 1996. A Handbook of Kalo Basics for its planting, care, preparation & eating. Wai'anae: Cultural Learning Center at Ka'ala.

Enos, Eric. Pers. comm. 7/21/14.

Fenstemacher, Lolana. Pers. comm. 10/26/06 and 7/30/14.

Hawai'inuiākea School of Hawaiian Knowledge. n.d. Ka Papa Lo'i o Kānewai. Website http://manoa.hawaii.edu/hshk/ka-papa-loi-o-kanewai/

Ka Papa Lo'i o Kānewai. n.d. Brochure.

Kim, Gwen. 1999. History of the 'Onipa'a Nā Hui Kalo. 'Onipa'a Nā Leo Vol. 1 No. 1, March.

Koani Foundation. 2012. Cultural Kipuka – A Visit With Eric Enos. Video posted Mar. 11. Website http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tl7DJRYd26U

Levin, Penny. Pers. comm. 7/11/14

Mahi, Kina. Pers. comm. 12/6/06.

Nā Maka o ka 'Āina. 1999. Charles Kupa & Marion Kelly, Ka Papa Lo'i 'o Kānewai, May 14, 1990. Video.

Onwueme, Inno. 1999. Taro culture in Asia and the Pacific. FAO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific (Bangkok) Report 1999/16.

Pang, Gordon Y.K. 2006. Revered kupuna 'Anakala Ka'anana. The Honolulu Advertiser, July 27.

Spencer, Sharon. 2008. From a weed-choked forest to a lo'i. QLCC Windward Newsletter, Vol. 2, No. 1.

Spencer, Sharon. Pers. comm. 6/20/14 and 6/23/14.

Tani, Carlyn. 1994. Lo'i hukihuki 'ia – The taro patch tug-of-war. Video.

Tummons, Patricia. 2001. The Heart of Halawa. Land & People, Spring. Website http://www.tpl.org/magazine/heart-halawa%C2%97landpeople