EcoTipping Points

- How do they work?

- Leveraging vicious

cycles to virtuous - Ingredients for success

- Create your own

EcoTipping Points!

Stories by Region

- USA-Canada

- Latin America

- Europe

- Middle East

- South Asia

- Southeast Asia

- East Asia

- Africa

- Oceania-Australia

Stories by Topic

- Agriculture

- Business

- Education

- Energy

- Fisheries

- Forests

- Public Health

- Urban Ecosystems

- Water and Watersheds

Short Videos

- Saving a Coral Reef and Fishery (Apo Island, Philippines)

- Community Gardens Reverse Urban Decay (NYC, USA)

- Community Forests Reverse Tropical Deforestation (Thailand)

- Escaping the Pesticide Trap (India)

- Rainwater Harvesting and Groundwater Replenishment (Rajasthan, India)

How Success Works:

- Saving a Coral Reef and Fishery (Apo Island, Philippines)

- Community Gardens Reverse Urban Decay (NYC, USA)

- Community Forests Reverse Tropical Deforestation (Thailand)

- Escaping the Pesticide Trap (India)

- Rainwater Harvesting and Groundwater Replenishment (Rajasthan, India)

Human Ecology:

Principles underlying

EcoTipping Points

Stories of Public Health

In-depth (based on site visits with extensive interviews)

- Honduras - The Monte Verde Story: Community Eradication of Aedes aegypti (the mosquito responsible for Zika, dengue, and chikungunya) - A humble community uses biological control to free itself from the mosquito and the diseases.

- Vietnam - Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever, Copepods, and Biological Control of Mosquitoes - Community participation enlists a tiny predator of mosquito larvae to eradicate the dengue-fever mosquito, liberating a million people from the disease.

Capsule (shorter pieces which appear below)

- Mozambique - Ecological Sanitation - Using music to promote low cost, environmentally sustainable “ecological sanitation,” a process to transform human waste into nutrient-rich agricultural fertilizer.

- Uganda - AIDS control - A holistic approach makes Ugandan AIDS control efforts exemplary.

- USA - Hawaii (Oahu) - Kokua Kalihi Valley: A Holistic Approach to Health - Kokua Kalihi Valley community health center integrates the health of the people and the health of the land.

Mozambique - Ecological Sanitation

- Author: Adapted from the Goldman website (with permission)

- Posted: July 2008

Using music to spread the message of ecological sanitation to the most remote corners of Mozambique, Feliciano dos Santos is empowering villagers to participate in sustainable development and rise up from poverty. In Niassa province, many villages lack even basic sanitation infrastructure. Without reliable access to clean water and waste management systems, the population is highly susceptible to disease. Santos, who grew up in the region, today heads an innovative program that is bringing new hope to Niassa. With his internationally-recognized band, Massukos, Santos uses music to promote the importance of water and sanitation in Mozambique. His program is now serving as a model for other sustainable development programs around the world.

Sanitation and Poverty

Throughout much of Africa, the lack of proper sanitation poses significant challenges to development. When drinking water is compromised, disease often follows. The World Health Organization estimates that 80 percent of all sickness in the world is attributable to unsafe water and sanitation. More children under five die from water-borne illnesses than AIDS. Recognizing both the environmental and societal risks associated with poor sanitation, the United Nations has declared 2008 the "Year of Sanitation" in order to bring further attention to the issue worldwide.

In Mozambique, more than half the population lives in extreme poverty without access to basic sanitation. The northernmost province of Niassa is one of the poorest and most isolated regions of the country. Most of its nearly one million inhabitants live in small villages dispersed throughout the province, which is as large as New England, yet has only 170 kilometers of paved road.

Waste Fuels Sustainable Development

Sanitation continues to be a taboo subject throughout the world, though it remains one of the most pressing problems in poverty-stricken regions. Santos has successfully found ways to discuss human waste management techniques with villagers through both grassroots outreach and music. He grew up in Niassa with no clean water or proper sanitation and is disabled from polio. As an adult, he has focused on improving living conditions in the region. Santos understands that environmental and health problems are interrelated in regions dealing with poverty issues like Niassa. As the director of Estamos, he works directly with villagers to provide community sanitation, promote sustainable agriculture, lead reforestation projects and support innovative HIV/AIDS initiatives. Santos believes that sanitation and water supply issues must be solved in order for other development projects to take root.

Santos and Estamos promote low cost, environmentally sustainable "ecological sanitation," a process that uses composting toilets, called EcoSans, to transform human waste into nutrient-rich agricultural fertilizer. Typically, a family will use an EcoSan for a number of months, adding soil and ash after each use. The pit is then buried and left for eight months, and the family moves on to another pit. During the eight months all the harmful pathogens die off, leaving a rich fertilizer that can be dug up and used in the fields. The compost not only provides natural fertilizer, but also enhances the soil's water-retention capacity. Families using ecological sanitation report markedly fewer diseases, a 100 percent improvement in crop production, and improved soil retention. Before ecological sanitation, many villages used costly artificial fertilizers on their crops, and often were barely able to feed their families. By using the compost instead of artificial fertilizer, many are able to produce more food than they need and can generate a small income by selling some of their harvest.

Santos and Estamos believe that no sanitation system or behavior change should be imposed on villagers by an external NGO. As an insider, Santos and his team lead participatory workshops in which villagers come to understand their sanitation options, and, if they like, choose the option they prefer and build it themselves.

Since Santos and Estamos began their work in Niassa in 2000, they have helped thousands of people in hundreds of villages gain access to clean water and ecological sanitation. This is a considerable achievement considering the lack of infrastructure in Niassa's remote villages. Estamos continues to grow and is now working in three districts in northern Mozambique. In one remote area, a local chief working with Estamos is leading a group of 70 villages to achieve 100 percent sanitation coverage. This achievement would be the first of this magnitude in Mozambique.

Empowerment through Music

Santos's band, Massukos, incorporates the sanitation message into music, performing in villages across Niassa and at times around Mozambique and abroad. Since Santos began his music-based outreach, people throughout Niassa and Mozambique have begun to focus more on the country's rural sanitation problems. By connecting with Mozambique's rich performance traditions, Santos and Estamos connect to villagers in a culturally appropriate way through music and theater. When Santos and the band arrive in a Niassa village, the entire local population often appears to hear them and their message. But the music is not the only reason for Estamos's success. In July 2007, Massukos traveled to the UK where they released their album "Bumping" and performed at the World of Music, Arts and Dance (WOMAD) festival.

Feliciano dos Santos is a recipient of the Goldman Environmental Prize. For more information see the Goldman Prize website.

Uganda - AIDS control

- Author: Amanda Suutari

- Posted: May 2005

As one of the first African countries to experience the HIV/AIDS epidemic and one of the first to show declines in infection rates in 1996, Uganda has become a model of how a nation with limited resources and health care services can manage and control an epidemic of unprecedented scale. When the first cases of HIV/AIDS began to appear in 1982, some 50% of the country had access to health care and less than 30% had access to safe water. The disease was initially limited to people who traveled frequently such as long-distance truck-drivers or prostitutes, and was clouded by mystery, rumor and superstitions such as witchcraft.

HIV/AIDS went from being a disease to an epidemic, and in 1986 Uganda's health minister publicly announced the situation during a World Health Organization conference in Geneva. This marked the beginning of political frankness which created conditions for the mass public education campaigns that followed. (This could be contrasted with the Chinese government's handling both of SARS in 2003 and its own AIDS epidemic, where existence of both diseases has been denied or downplayed, allowing them to spread in a culture of ignorance and misinformation.)

Uganda took a multi-pronged, pan-sectoral approach which was both centralized and decentralized where appropriate. It mobilized all levels of legal, political, administrative, health, non-profit, for-profit, research institutions, international donors, and international institutions (WHO etc):

- It launched massive education campaigns, aimed at de-stigmatizing the disease, targeting different age groups about issues related to their age or situation, including delaying sexual relations, use of condoms, avoidance of casual sex, and fidelity. This was coordinated through mass media but also decentralized through folk media, religious organizations, educational institutions, community groups and non-governmental organizations. Initially the strategy was to instill fear in the public, but it became clear that this had only limited, short-term success and authorities learned that the approach had to be made more hopeful and positive.

- Health authorities were given support by government and international donors to screen blood banks, and to improve services related to detection, testing, counseling, and make them widely available, especially to the poor, who might be doubly stigmatized and less likely to seek help. Drugs for opportunistic infections were also made available to patients free of charge.

- Understanding AIDS/HIV was a gender issue with womens' participation as its basis; improvements were made to the public education system to make it more available to all, especially girls. At the legal level, female lawyers banded together to change laws and punishments related to rape and statuatory rape. Credit facilities targeted towards women were established, enabling women to start small businesses.

In 1992 the Uganda AIDS Commission was established to coordinate and harmonize efforts from all corners. While the epidemic is far from over and will continue to incur high, long-term costs, Uganda is seen as an international leader in controlling HIV/AIDS. Reasons for its success are linked to these factors:

- coordination

- decentralization

- a holistic, integrated approach

- a clear understanding that HIV/AIDS was much more than a public health issue

- flexibility which allowed for creativity and innovation while improving institutional conservation

- openness

- active participation of women

For more information visit the World Health Organization

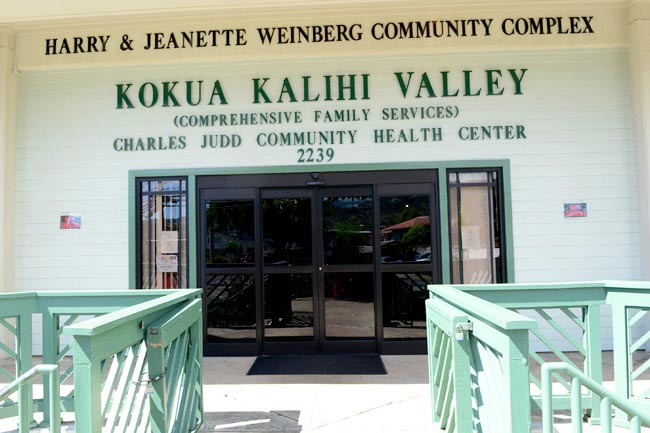

USA - Hawaii (Oahu) - Kokua Kalihi Valley: A Holistic Approach to Health

- Author: Regina Gregory

- Posted: January 2013

Kalihi is a large low-income neighborhood of Honolulu, Hawai‘i. About one third of the residents are foreign-born immigrants from Asia and the Pacific Islands. About 15% fall below the official poverty level. The community is home to several public housing projects, including the two largest in the state. It has been declared a Medically Underserved Area.

Kokua Kalihi Valley (KKV) is one of 14 community health centers in Hawai‘i, where people are served regardless of whether they have medical insurance, and are billed based on ability to pay. KKV had very humble beginnings: It began 40 years ago, in 1972, as a non-profit organization with four outreach workers. Dr. Charles Judd and Dr. William Myers began providing medical services at Kalihi Valley Homes. The following year, KKV purchased and renovated two military surplus trailers to serve as clinics and added a dentist to the staff. Since then, KKV has grown to include six locations, including a main clinic, a clinic and a resource center in one of the public housing projects, an elderly service center, a bicycle exchange warehouse, and an upper-valley nature park/community garden. KKVstaff has grown to 160 employees serving over 10,000 community members each year.

KKV main clinic

Photo: Honolulu MidWeek 12/12/12

Unlike other community health centers, KKV limits eligibility for service to people in the service area—basically, the 96819 zip code. But it provides a much broader range of services than most community health centers. Besides the usual primary medical care, dental and mental health services, KKV offers “enabling services” such as case management, transportation, translation (for 20 Asian and Pacific Island languages), and a “medical-legal partnership for children” to help immigrant families with legal matters, especially those pertaining to children. The main clinic was recently expanded into a nearby building, with funding from an assortment of government agencies and charitable organizations. It houses not only more clinic space, but also a commercial kitchen and space for micro-enterprises like the women’s sewing project, designed to improve economic self-sufficiency.

What sets KKV even further apart from the ordinary health center is its effort to reunite people and the land. This began around 2003 with the Active Living By Design project. KKV clientele are not too keen on exercise in the conventional sense, but very excited to grow their own food. The idea was to encourage people to be more physically active while growing and eating healthy foods—keys in managing illnesses such as diabetes. With a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, KKV procured a warehouse for an instructional bike exchange and a low-cost, long-term lease for a 100-acre parcel of state land deep in the valley—land which, incidentally, the community had fought to protect from development for 30 years. The vision was to create a nature park with hiking and biking trails, and an organic community garden.

The land was named Ho‘oulu ‘Aina (transl. to make the land grow). With volunteer labor from community college trade students and various community groups, the dilapidated home on the land was completely renovated and now serves as the caretaker’s residence and community meeting hall complete with a large kitchen.

Sign at Ho‘oulu ‘Aina entrance

There is less emphasis on hiking and biking than originally intended, but the garden is flourishing. Between coconut, banana, and papaya trees, there is a lush mosaic of vegetables, herbs and spices, and berries. Other garden patches (e.g., kava) are further into the forest. Traditional lo‘i (taro patches) are planned for the future, using water from Kalihi Stream.

Ho‘oulu ‘Aina organic community garden

Gardening is just one aspect; Ho‘oulu ‘Aina has four program areas:

- Hoa ‘Aina (community access) to create unique opportunities for quiet recreation, contemplation and pleasure in Kalihi’s natural environment

- Mahi ‘Aina (community food production) to share knowledge and offer a variety of opportunities regarding healthy food, exercise, increased self-sufficiency, and a reconnection with the land, nature and diverse cultures

- Koa ‘Aina (native reforestation) to restore health and balance to Kalihi’s watershed and native upland forests

- Lohe ‘Aina (sacred places and stories) to restore and revitalize ancient sites, perpetuating cultural knowledge and instilling a sense of honor in the ahupua‘a [watershed] of Kalihi

It is now a favorite community meeting place as well as cultural learning center. Community work days are on Wednesdays and the third Saturday of each month. On other days, Ho‘oulu ‘Aina is busy with school children or farming classes or even nursing students coming to learn about medicinal plants. On the Wednesday I visited, expecting to get muddy, the activity was arts and crafts. About 25 people of various ages and nationalities gathered to stamp and stencil pouches, and make fiber Christmas ornaments, shell necklaces, and coconut cups, while sharing knowledge about Hawaiian culture. Some of the people are KKV patients, so in the interest of privacy I was asked not to photograph anyone. While we worked lunch was being prepared in the kitchen.

To spread the food and the community spirit throughout the valley, KKV initiated its Roots Project with a Kresge Foundation grant for unique projects that integrate community health and prevention with primary care. This land-to-table initiative integrates food production at Ho‘oulu ‘Aina with food preparation and sharing, at KKV’s new community kitchen and at imu (traditional underground ovens) elsewhere in the valley.