EcoTipping Points

- How do they work?

- Leveraging vicious

cycles to virtuous - Ingredients for success

- Create your own

EcoTipping Points!

Stories by Region

- USA-Canada

- Latin America

- Europe

- Middle East

- South Asia

- Southeast Asia

- East Asia

- Africa

- Oceania-Australia

Stories by Topic

- Agriculture

- Business

- Education

- Energy

- Fisheries

- Forests

- Public Health

- Urban Ecosystems

- Water and Watersheds

Short Videos

- Saving a Coral Reef and Fishery (Apo Island, Philippines)

- Community Gardens Reverse Urban Decay (NYC, USA)

- Community Forests Reverse Tropical Deforestation (Thailand)

- Escaping the Pesticide Trap (India)

- Rainwater Harvesting and Groundwater Replenishment (Rajasthan, India)

How Success Works:

- Saving a Coral Reef and Fishery (Apo Island, Philippines)

- Community Gardens Reverse Urban Decay (NYC, USA)

- Community Forests Reverse Tropical Deforestation (Thailand)

- Escaping the Pesticide Trap (India)

- Rainwater Harvesting and Groundwater Replenishment (Rajasthan, India)

Human Ecology:

Principles underlying

EcoTipping Points

Germany - Freiburg - Green City

- Author: Regina Gregory

- Posted: January 2011

Long famous for its cathedral, university, and cuckoo clocks, Freiburg is now also famous as a “Green City.” It excels in the areas of transportation, energy, waste management, and land conservation, and has created a green economy that perpetuates even more environmental progress.

Photo: Courtesy Freiburg Wirtschaft Touristik u. Messe GmbH

Freiburg, a city of about 220,000 people and 155 km2 of land, is located in the southwest corner of Germany, at the edge of the Black Forest and near the borders with France and Switzerland. It was founded in the year 1120, and through the centuries of growth and modernization still maintains its Old World charm and surrounding beauty.

With its large academic community, Freiburg was an early stronghold of the Green Movement in the 1970s. A successful protest against a nearby nuclear power plant is thought to be the galvanizing moment. According to Energie-Cites (1999), “The most committed leaders [of the anti-nuclear movement] joined the political arena, the administration, the utilities, found a job in educational or research activities or founded green-spirited companies.” Freiburg’s mayor and one-fourth of the city council are Green Party members.

Freiburg promotes itself as a Green city—especially in the areas of transportation, energy, waste management, land conservation, and green economics—and the city has won various national and international environmental awards. Actually, in some respects (e.g., waste management), Freiburg is much like other German cities. But in the areas of energy and green economics, it is particularly outstanding.

Transportation

Freiburg was heavily bombed during World War II; little remained of the city center besides the cathedral. It was decided to rebuild without altering the city’s character, following the old street plan and architectural style. As the roads were rebuilt, they were widened just enough for a tram track, not for more lanes of cars.

In 1969 Freiburg devised its first integrated traffic management plan and cycle path network. The plan, which aims to improve mobility while reducing traffic and benefitting the environment, is updated every 10 years. It prioritizes traffic avoidance and gives preference to environment-friendly modes of transport such as walking, cycling, and public transit. Traffic avoidance is achieved in conjunction with urban planning that makes Freiburg a city of “short distances”—a compact city with strong neighborhood centers where people’s needs are within walking distance.

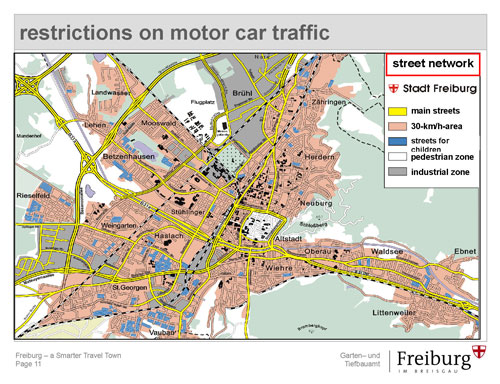

In 1973 the entire city center was converted to a pedestrian zone (shown in white on the map below).

Source: Schick, n.d.

The public transit network has been steadily expanded and modernized since 1972. Today the tramway network comprises 30 km and is connected to the 168 km of city bus routes as well as to the regional railway system. 70% of the population lives within 500 meters of a tram stop, and the trains appear every 7.5 minutes during rush hours. Besides working to make public transport convenient, fast, reliable and comfortable, the city administration also made it cheap. In 1984 the city-wide Environmental Card was introduced for 38 DM per month (US$13 at the time) for unlimited travel within the urban network (tram and bus). A monthly ticket had previously cost 50 DM. In 1991 the Environmental Card was replaced with a RegioCard. The current price is 47 euros (US$61) per month. The RegioCard allows passengers unlimited use of not only Freiburg’s urban transit but also public transport in the whole region—about 2,900 km of routes of 17 different transportation companies, plus the tracks of the German Rail. In its first year alone, the card is credited with increasing regional public transit trips by 26,400 while the number of car trips fell by 29,000. Besides this, there is a policy that any ticket for a concert, sports event, fair, or big conference also serves as a ticket for public transport.

City tram

Source: Schick, n.d.

Freiburg’s administration has developed over 400 km of cycle paths. This includes bike-friendly streets, streetside bikepaths, and separate bikepaths, e.g., along the river Dreisam. About 9,000 bicycle parking spaces were also developed, including “bike and ride” lots at transit stations. Cycling is promoted with free maps and other information.

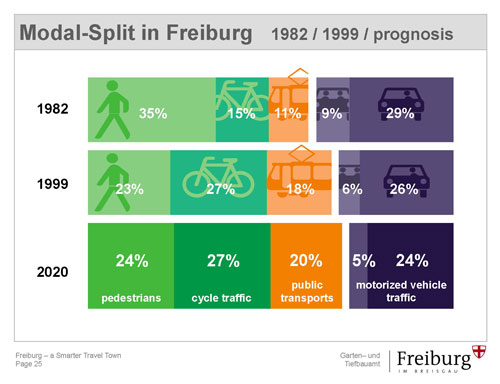

As a result of all this, between 1982 and 1999, the contribution of cycling to the city’s volume of traffic increased from 15% to 28% and public transport from 11% to 18%, while miles travelled by car fell from 38% to 30% of the total (see chart below).

Source: Schick, n.d.

Another notable aspect of Freiburg’s transport policy is traffic calming. As the map above shows, for most streets (other than main streets) the speed limit is 30 km (19 mi) per hour. On some streets (shown in blue) cars can travel no faster than walking speed, and children are allowed to play in the streets. Residents may apply for this status for their street by petitioning the city’s Department of Civil Engineering.

Parking space management also contributes to the reduction of motor vehicle traffic. Multi-story garages are located at the edge of residential districts and at major mass transit stations. The new district of Vauban is one extreme example of parking space management. Parking there is limited to garages on the outskirts of the neighborhood. Each parking space costs 18,000 Euro (approx. US$23,000). To avoid this cost, some people are said to lie about owning a car in their annual declarations. But officially there are about 250 motor vehicles per 1,000 Vauban residents, compared to 423 for Freiburg as a whole (and 500 for Germany).

Car-sharing is also encouraged. About 140 vehicles currently are available through the Freiburger Auto-Gemeinschaft e.V. Members have occasional use of a car (e.g., for big shopping trips or going to the mountains for skiing, as one woman interviewed by Purvis (2008) explained). They also receive a yearly free pass for public transport within the city, and a 50% discount on national rail tickets.

Looking to the future, the official “traffic development plan 2020” (published in 2008, see Huber-Erler et al.), after consideration of various scenarios and their costs, includes 4 measures for pedestrian traffic, 13 for bicycle traffic, 12 for city public transport, 7 for regional public transport, and 19 for motor vehicles.

Energy

Freiburg’s progressive energy policy has its roots in the early 1970s, when the state of Baden-Württemberg’s plan to build a nuclear power plant in the town of Wyhl, just 30 km away, provoked intense protest among Freiburg residents. Thomas Dresel (who is now the city environmental manager) recalls that there was widespread civil disobedience; the conflict began to look like a “civil war.” Dresel says that as the protesters stood there in the mud (created by police water cannons), they began to ponder the question, If not nukes, then what? The plan was dropped in 1975, and in the years since then Freiburg has sought to become a model of sustainable energy development. The Chernobyl disaster of 1986 and concern over acid rain damaging the Black Forest—and more recently concern regarding climate change—strengthened the determination to find alternatives to nuclear and fossil fuel energy. Germany’s national energy policy, such as the decision to phase out nuclear power and the 2001 federal renewable energy law, which requires utilities to buy power from independent producers, promote such a policy as well.

Freiburg’s energy policy has three basic pillars: Energy saving, efficient technologies, and renewable energy sources.

Energy Saving

In 1992, Freiburg’s building design standards were amended to require that all new houses built on city land (or land sold by the city) use no more than 65 kilowatt-hours of heating energy per square meter per year, compared to the national standard of 75 kWh/m2/yr. This adds about 3% to the cost of the house, but the energy savings make it worthwhile in a short time. It is estimated that the standard reduces heating oil consumption from 12-15 liters to 6.5 liters per square meter. The entire new districts of Vauban and Rieselfeld were built according to this standard.

To improve energy efficiency in existing buildings, Freiburg instituted a support program for home insulation and energy retrofits. About 1.2 million Euros in subsidies were provided in 2002-2008, complementing about 14 million Euros of investments. Reduction of energy consumption averaged 38% per building. Most municipal buildings (e.g., schools, offices) were also retrofitted.

In 2008, after the federal government revised its standard downward, so did Freiburg—to ensure that the city stays at the forefront of low-energy development. A two-step revision was to be implemented in 2009 and 2011 to move new housing even closer to the “passive house” standard of just 15 kWh/m2/yr. These cost 10% more to build, but can achieve an 80-90% reduction in energy consumption. Purvis (2008) describes a passive house he visited:

It is 6C outside, and a dusting of snow can be seen …. In Meinhard Hansen’s apartment, however, it is perpetual summer; the sun streams in through tall, south-facing windows and a gauge on the wall reads ‘24C.’ Next to it, the words ‘Heizung 0’ appear in a small glass window. ‘Heating, zero,’ Meinhard translates. ‘In fact, we haven’t switched the heating on for weeks….’ On one wall there is a radiator, but it is stone cold…. Super-insulated with foam and lagging up to 30 cm thick, the flat is triple-glazed and externally sealed. Fresh air enters at ceiling level and is sucked out through a funnel on one wall. ‘The heat from the warm air going out is transferred to the cold air coming in,’ says Meinhard, Freiburg’s chief architect and a world authority on passive houses. So far, his company has built about 100.

Opening a cupboard, he shows me how the cold and warm ducts meet in a knot of corrugated silver piping.

While consumption of heating oil has decreased, Freiburg’s electricity consumption increased by 3% between 2004 and 2010. The goal had been a 10% reduction. This is mainly due to population increase (about 1% per year) and also to growing commercial and industrial demand. Per capita consumption actually went down by 1.6%.

Efficient Technology

Chief among the efficient technologies developed in Freiburg (in fact, the only one mentioned in the literature) is combined heat and power (CHP). As the name implies, CHP produces both electricity and heat by capturing the waste heat from electricity production to generate more electricity and useful heat, e.g., for district heating systems. About 50% of Freiburg’s electricity is now produced with CHP (compared to just 3% in 1993). There are 14 large-scale CHP plants and about 90 small-scale CHP plants (e.g., at the city theater and indoor swimming pools). The two large-scale plants located near landfills use landfill gas as fuel. The others use natural gas, biogas, geothermal, wood chips, and/or heating oil. Vauban’s CHP plant, for example, uses 80% wood chips and 20% natural gas to provide the district with electricity and heat. An important concomitant development is new district heating systems which can replace individual oil or gas burning furnaces.

CHP plant in Vauban

Source: Wörner n.d.

The increase in CHP’s share from 3% to 50% has enabled Freiburg to reduce its reliance on nuclear power from 60% to 30%--and provides local heating at the same time.

Renewable Energy Sources

Renewables at Freiburg’s disposal include solar, wind, hydropower, and biomass. (Geothermal is also a possibility, but its use to date has been negligible.)

Solar. Solar energy is by far the most visible renewable resource used in Freiburg. The city is home to approximately 400 photovoltaic installations on both public and private buildings. Prominent among these are:

- The 19-story façade of the main train station

- The roof of the convention center

- The roof of the soccer stadium

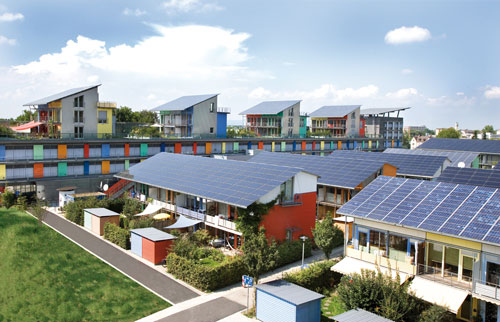

- The Solarsiedlung (Solar Settlement) and its neighboring Solarschiff (Solar Ship) business park

- The Solar Factory (SolarFabrik)

- The “Heliotrope,” a structure that rotates to follow the sun

- The roof of the city’s waste management offices and its recycling center

Solar Settlement and business park

Source: Website plusenergiehaus.de

Heliotrope

Source: Wörner n.d.

SolarFabrik

Source: Freiburg Wirtschaft Touristik u. Messe GmbH

Currently Freiburg’s 150,000 m2 of photovoltaic cells produce over 10 million kWh/year. The 60 “plus-energy” homes of the Solar Settlement create more energy than they consume, and earn 6,000 euros per year for their residents.

Solar thermal (mostly hot water) panels cover 16,000 m2, but their total contribution to Freiburg’s energy supply has not been quantified.

Wind. Unlike coastal or plains areas, Freiburg is not ideally suited for wind energy, since it is in a hilly, wooded area. Still, there are five windmills situated on hilltops within the city’s boundaries, producing an average of 14 million kWh/year. The planning authority for more windmills is now in the hands of a regional council (Regionalverband Südlicher Oberrhein). Confounding Freiburg’s plan for 10% renewables by 2010, the regional authority did not plan any new wind projects in the Freiburg municipality.

Windmills near Freiburg

Source: Ökostromgruppe Freiburg

Hydropower. The Dreisam River runs through Freiburg, but there are no major hydropower stations. Small, eco-friendly run-of-the-river facilities are on the river and on smaller canals and streams. Hydropower generation within Freiburg amounts to about 1.9 million kWh/year, but the regional utility, badenova, also imports hydropower. According to badenova literature, the 120,000 customers who selected “regiostrom basis”—a slightly more expensive, nuclear-free alternative to conventional power—receive half their electricity from hydropower plants in Switzerland and Austria, and half from CHP plants. The 10,000 customers who selected “regiostrom aktiv” are guaranteed 100% electricity from renewable resources—a hydropower plant in Norway. The 1.8 euro-cents per kWh extra they pay goes to the regiostrom fund for developing more renewable energy. (How the renewable electrons make their way to the higher-paying customers remains unclear.)

Since January 2009, according to badenova, Freiburg’s 60 trams have been running on 100% renewable energy (80% hydropower and 20% a mix of other renewables).

Biomass. With 16.6 million kWh/year, biomass has the largest share of Freiburg’s renewable electricity generation. The Black Forest provides an ample supply of wood chips and wood pellets (much of it waste from woodworking industries). The Solar Factory burns rape seed oil in its CHP plant.

A more exciting innovation is the development of biogas. Through a joint venture of private and city-owned waste management companies, the organic waste from Freiburg’s households is fed into a digester that produces biogas and compost. The biogas is burned in a CHP plant to produce about 7 million kWh of electricity, plus heat. In 2009, badenova subsidiary WÄRMEPLUS switched all three of Freiburg’s indoor swimming pools to biogas for their CHP generators. The same year, badenova began work on three of five planned biogas projects in the region, using mainly corn silage and cow manure as the feedstock. One of the projects is an existing biogas plant where badenova is adding a refinery to improve the quality of the gas by removing the high carbon dioxide content, making it equivalent to regular natural gas. The gas will be used in CHP plants to produce electricity and heat, but it will also be mixed with conventional natural gas to create “BIO 10,” a 10% biogas mixture. This is especially important because since 2008, any homeowner who modernizes his/her heating system must switch to at least 10% renewable energy for heat. On a smaller and more experimental scale, one apartment building in Vauban is equipped with vacuum toilets connected to a biogas digester; in 8 years of experience it seems to work satisfactorily.

Unfortunately, Freiburg’s total electricity demand is well over 1,000 million kWh/year, so despite all the efforts described above, only 3.7% of the city’s electricity comes from locally generated, renewable resources. This is the same percentage as in 2005, and far short of the 10% goal set by the city council in 2004. However, if solar water heating and imported renewables were included, the number would be much higher. Mayor Salomon expects that the CO2 emissions reduction report (goal: 40% reduction versus 1992 by 2030) will yield much better results, since it includes heat and transportation as well as electricity, and has a much longer timeline.

Waste Management

Everywhere in Germany, the volume of solid waste is declining because of waste avoidance and aggressive recycling efforts. Around 70% of the country’s waste is recovered and reused. The number of landfills fell from 50,000 in the 1970s to 200 today.

Each household or apartment building is equipped with three bins: one for paper, one for organic food and garden wastes (the “bio-bin”), and one for non-recyclables (“rest-waste”). They also have a “yellow sack” for packaging, such as yogurt cups and tin cans. The bins are emptied and the sacks picked up regularly by the local waste management company. In Freiburg the bio-bin is emptied once a week, the others once every two weeks. Glass must be sorted by color and deposited in community bins. There are 350 of these in Freiburg. Hazardous wastes like batteries, paints, pesticides, etc. can be dropped off at temporary collection sites or at recycling yards. Freiburg has 26 rotating collection sites that each accept hazardous waste twice a year, plus three permanent recycling yards. In addition, Freiburg recycles over 1 million corks per year. These are processed into “Recykork,” an eco-friendly insulation material, by handicapped workers at the local Epilepsy Center. Mayor Salomon points out that Freiburgers recycle more than the state or national average.

Community glass bins

Source: abfallwirtschaft-freiburg.de

Apart from making recycling easy for consumers, Germany has strong laws that start at the other end of the waste cycle—with manufacturers. Since 1996, manufacturers must consider waste avoidance, waste recovery, and environmentally compatible disposal in designing products. In fact, under the concept of “product responsibility,” manufacturers are required to collect and recycle or reuse their packaging after it is disposed of by consumers. Because of the complexity involved with that, the companies formed the non-profit organization Duales System Deutschland (DSD) GmbH. Manufacturers pay a membership fee to DSD and are then allowed to print the “Green Dot” on their packaging to show they have paid for proper disposal. The “Green Dot” items go into the “yellow sack” mentioned above and are recycled by DSD. According to Look (2009), in 2007 over 88% of Germany’s packaging waste was recovered.

Freiburg reduced its annual waste disposal from 140,000 tons in 1988 to 50,000 tons in 2000. This is burned for energy at an incinerator 20 km from the city. As mentioned above, the contents of the bio-bins are fed to a biogas digester.

Land Conservation

Freiburg is also “green” in appearance. It is home to Germany’s largest communal forest, covering over 40% of the municipal territory. The forest is home to Germany’s tallest tree—a 63-meter douglas fir. It has a surprisingly diverse terrain and ecosystems—from high mountains to boggy lowlands. About 44% of the forest is used as an “environmentally appropriate economic forest.” Wood is harvested at a rate of 35,000 m3, which is about three-fourths of the amount that grows back in a year. Monocropping is avoided; there is no clearcutting and no use of pesticides. For this sustainable management Freiburg’s Forestry Office earned certification from the Forest Stewardship Council, and its timber can be marketed with the FSC eco-label. The remaining 56% of the city forest are nature conservation areas—50% managed and 6% wild.

Freiburg’s city forest

Source: Inspirenation 2008

According to the Forestry Office, besides providing wood, and jobs in the forestry and woodworking sectors, the city forest has a wide variety of beneficial functions. It:

- serves as the city’s “green lungs” and cleans the air

- moderates temperature

- protects the soil

- stores water

- is a natural and free recreational resource

- provides habitat for wildlife, including rare and endangered species

- gives food from deer, wild pigs, and goats

- beautifies the landscape

Besides the 5,000 hectares of forest, Freiburg has over 600 hectares of parks and 160 playgrounds providing greenery, recreation, and biodiversity. The parks range from the carefully manicured and flowery site of a former international flower show, to the more unkempt nature conservation areas. Pesticides are not used, and only indigenous tees and shrubs are planted. Changing the lawn mowing schedule from 12 times to only twice a year has “markedly revived the biodiversity in the meadows.” 22,000 trees were planted in the parks, and the same number along streets.

Park with bike path along the Dreisam River

Source: City of Freiburg (n.d.)

There are also 3,800 small garden allotments on the outskirts of the city, which serve as private oases for the city dwellers as well as a source of fresh fruits and vegetables. The number is expected to increase, according to the new land use plan.

All this green space is the result of deliberate urban planning that seeks to keep development compact while accommodating population growth. In the new neighborhoods of Vauban and Rieselfeld, for example, the homes are four- to five-story apartment buildings instead of single-family houses, allowing for more green space. (In the Rieselfeld district, 240 hectares were designated as landscape conservation area and only 78 hectares for residential development.) Shops and offices are located on the ground floor of the apartment buildings, allowing residents easy access, on foot or bicycle, to their daily needs—so that “no supermarkets will be constructed on green meadows.” The urban planning has been participatory. For the new Land Use Plan 2020, citizens formed 19 working groups to discuss potential construction areas and make recommendations to the city council.

Green Economy

Renewable energy production is encouraged with tax credits from the federal government and subsidies from the regional utility (badenova provides 200 euros for solar water heaters and 900 euros for photovoltaic systems). But especially noteworthy as an economic model are grassroots financing schemes that allow concerned citizens to invest directly in renewable energy resources. For example, through one local association for the promotion of renewable energy (fesa, or Förderverein Energie und Solar Agentur e.V.), citizens invested over 6 million Euros in 9 windmills, 8 photovoltaic arrays (including the soccer stadium), 1 hydropower plant, and a major energy conservation retrofit project at the Staudinger public school. Investors get a return on their investment and, in the case of the soccer stadium, free season tickets. Under the heading “with us one can buy power plants,” badenova (2009) describes four such plans, the most recent of which bundles wind, hydro, and solar power due to a dearth of new wind sites.

Thus Mayor Dieter Salomon credits the citizens themselves for Freiburg’s success:

“Freiburg has developed its profile from eco-capital into the leading centre of competence for alternative energy. The city’s many small and large scale alternative energy facilities exist thanks to the dedication of the citizens – citizens who equip their own houses with solar panels, hold shares of communal facilities and order regionally produced electricity from renewable energy through our local energy supplier Badenova” (Inspirenation 2008).

Freiburg has become the European Union’s “Solar Valley,” similar to California’s Silicon Valley. The economic benefits are especially noticeable in the sectors of manufacturing, research and education, and tourism. Overall the “environmental economy” employs nearly 10,000 people in 1,500 businesses, generating 500 million euros per year.

Freiburg companies produce not only state-of-the-art solar cells, but also the machinery needed to manufacture the cells. Companies such as Solarfabrik, Concentrix Solar, SolarMarkt, and Solarstrom are served by a wide web of suppliers and service providers. One exciting new development is Concentrix’s creation of solar cells that double the efficiency of photovoltaics by using lenses to concentrate the solar radiation. Overall about 80 business operations employ over 1,000 people in the solar technology industry.

A network of prestigious research institutions has developed in Freiburg, most notably the Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems (Europe’s largest solar research institute) and the Ökoinstitut. The International Solar Energy Society (a worldwide organization) has its headquarters in Freiburg. According to the City of Freiburg (n.d., p. 4),

Centres of private and public research investigating renewable energy resources, such as the Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems, function as a centre of gravity, around which hundreds of spin-off companies, service providers and organisations are based. These include: from the Solar Factory to the Regio Freiburg Energy Agency, from consultancies to solar architects, from a zero-emission hotel to the Future Workshop of the Chamber of Crafts. Also the farmers, foresters and organic vintners profit from the research done in the region by institutions such as the Viticulture Institute, the Forest Research Institute or the Albert Ludwigs University.

The city frequently hosts international conferences that serve the transfer of science and technology. The Photovoltaics Industry Forum was held in 2007, and the Intersolar conference was held in Freiburg every year from 2000 to 2008 (with 53,000 visitors in its last year). Intersolar moved to Munich, but the Gebäude-Energie-Technik (Building Energy Technology) fair takes its place. The city also hosts the annual Freiburg Solar Summits which attract people from around the world.

Environmental education is another booming business. According to the City of Freiburg (n.d., p. 4),

In the field of environmental education alone, 700 new jobs were created, among which was a university chair of environmental economics. In the scope of the Solar University, which obtained the status of an elite university in 2007, an Interdisciplinary Centre for Renewable Energies and an international masters study course “Renewable Energy Management (M.sc.)” have been established.

There is also a Solar Training Center for technicians and installers. Environmental education in schools (e.g. the Fraunhofer program for 9th and 10th graders) and outdoors (e.g., forest trails, deer park, and the Eco-Station at Seepark) encourages environmental consciousness in the younger generation.

Besides all the researchers, conference-goers, and students who come to Freiburg from around the world, the city’s green reputation also attracts eco-tourists. Even from as far away as China, South Korea, and Japan, eco-tourists—equipped with solar city maps and bicycles—enjoy the “solar tour.”

EcoTipping Points Analysis

Tipping Points and Feedback Loops

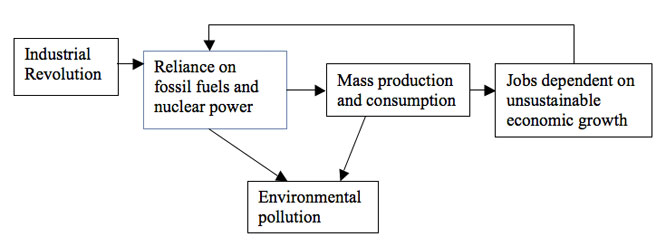

The roots of the problem can be traced back to the Industrial Revolution, when increased use of fossil fuels and new manufacturing technology led to mass production and mass consumption of goods. The economy was then “eating the earth” and polluting it as well. People’s livelihoods became dependent on this economy, and a vicious cycle of unsustainable economic growth developed.

The “positive tip” came in the form of an awareness of the economy’s unsustainability, and a desire to do something about it, which developed into the Green Movement. In Germany, the Green Movement—and Green Party—became quite strong. From 1998 to 2005 the country was governed by a “Red-Green Coalition” that was able to implement a number of important policies (e.g., phasing out nuclear power and promoting renewable energy).

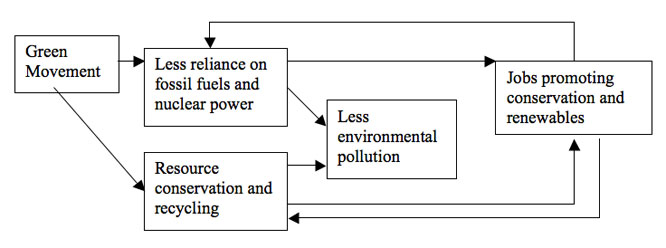

In Freiburg, the Green Movement became established in the early 1970s. The city’s Green Party mayor was elected in 2002, and re-elected in 2010 for another 8 years. The Green Party promotes resource conservation and a shift to renewable energy. The new “eco-economy” provides jobs that further these goals, and a “virtuous cycle” of progress toward greater sustainability is created.

Ingredients for Success

At least seven of the EcoTipping Points “ingredients for success” are apparent in Freiburg:

- Outside stimulation and facilitation. The planned nuclear plant at Wyhl in the early 1970s is said to have been a catalyst for Freiburg’s Green Movement. More recently, federal policies regarding waste management and renewable energy promoted Freiburg’s progress toward being a Green City. The European Union’s directive regarding combined heat and power undoubtedly also played a role.

- Strong democratic local institutions and enduring commitment of local leadership. Freiburg’s democratically elected mayor and city council, and the various local agencies, set crucial policy in the areas of transportation, energy, waste management, and land use. They also invest money and create jobs that further more environmental protection. Direct citizen participation is important especially in land use planning and energy investments. Participatory decision-making at the neighborhood level governs the Vauban neighborhood (see our related story at http://ecotippingpoints.org/our-stories/region-europe.html#Neighborhood).

- Co-adaptation between social system and ecosystem. The overall strategy for Freiburg’s development has always been to provide for the needs of the people while minimizing environmental harm. Recent improvements in human behavior (e.g., recycling and using public transit) benefit the ecosystem even more. And the green economy ensures that people and land prosper together.

- Letting nature do the work. Freiburg is working hard to maximize the use of sunshine for heating homes, heating water, and generating electricity. The large communal forest also provides valuable environmental services.

- Transforming waste into resources. Freiburg's extensive recycling system makes use of almost every conceivable waste. Paper, plastics, tin cans, glass, and even corks are converted to new raw materials. Energy is derived from wastes such as landfill gas, wood chips, waste heat (CHP), and organic household waste, which in addition provides a high-quality compost for gardens.

- Overcoming social obstacles. Freiburgers battled the state government over nuclear power decades ago, and now the problem is wind power. The “Black-Yellow Coalition” (Christian Democrats and Free Democrats) that rules the state of Baden-Württemberg is said to have a “wind blockade policy.” (The state government could change in the March 2011 elections.) Also, there seems to be conflict over wind with the regional energy planning authority. Moreover, a “Black-Yellow Coalition” is currently in power at the national level. The federal government recently decided to slow down the phase-out of nuclear power.

- Building resilience. Thanks to its green economy, plus another ingredient we notice in many stories—community solidarity and pride—Freiburg is likely to remain a Green City.

References

- badenova. 2009. Ökologie- und Nachhaltigkeitsbericht. Website

- Berg, Rick. 2009. Madison conservative visits the car-light Vauban neighborhood in Freiburg. The Daily Page, (Madison, Wisconsin), July 24. Website

- Breyer, Franziska. 2009. Freiburg Energy Policy: Approaches to Sustainability. Presentation at the Local Renewables Conference, Freiburg, April 28. Website

- Brunsig, Jürgen, Nadine Möller, and Jürgen Wixforth. n.d. Freiburg-Rieselfeld: urban expansion and public transport. Website

- C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group. n.d. Buildings – Freiburg, Germany. Website

- C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group. n.d. Transport – Freiburg, Germany. Website

- City of Freiburg. 2010. Dächer des städtischen Betriebshofs werden zur Stromproduktion genutzt. Website

- City of Freiburg. 2010. Ziel verfehlt mit Ansage. Website

- City of Freiburg. n.d. Freiburg Green City: Approaches to Sustainability. Website

- Dauncey, Guy. 2003. Freiburg Solar City. Website

- Energie-Cites. 1999. Thermal Solar Energy – Freiburg (Germany). Website

- European Academy of the Urban Environment. n.d. Freiburg: Low-energy Housing Construction Project. Website

- European Academy of the Urban Environment. 2001. Freiburg: Public transport policy as a key element of traffic displacement. Website

- Hildebrandt, Andreas. 2008. Traffic planning and Public Transport in Freiburg. Presentation at the Tsukuba 3E Forum, May 31, on behalf of VAG Freiburg. Website

- Huber-Erler, Ralf, Sebastian Hofherr, and Tomas Pickel. 2008. Verkehrsentwicklungsplan VEP 2020, Stadt Freiburg im Breisgau, Endbericht Mai 2008. City of Freiburg, Garten- und Tiefbauamt. Website

- Inspirenation. 2008. Sustainable Buildings, Transport and Energy Study Tour. Website

- Look, Marie. 2009. Trash Planet: Germany. Website

- Mayrhofer, Max. Creating reduced traffic areas in Freiburg/ Germany. Website

- Purvis, Andrew. 2008. Is this the greenest city in the world? The Guardian (UK), March 23. Website

- Salomon, Dieter. 2009. Freiburg Green City: Approaches to Sustainability. Presentation to European Green Capital Award, Brussels, Dec. 1. Website

- Schick, Peter. n.d. Freiburg – A Smarter Travel Town? Website

- Sperling, Carsten. 2002. Sustainable Urban District Freiburg-Vauban. Website

- UNEP Climate Neutral Network. n.d. Freiburg. Website

- Wörner, Dieter. n.d. Sustainable energy solutions for cities – case of Freiburg. Website

- Zurbonsen, Karl-Heinz. 2010. “Green City” is nicht grün genug. Stuttgarter Nachrichten, Oct. 11. Website