EcoTipping Points

- How do they work?

- Leveraging vicious

cycles to virtuous - Ingredients for success

- Create your own

EcoTipping Points!

Stories by Region

- USA-Canada

- Latin America

- Europe

- Middle East

- South Asia

- Southeast Asia

- East Asia

- Africa

- Oceania-Australia

Stories by Topic

- Agriculture

- Business

- Education

- Energy

- Fisheries

- Forests

- Public Health

- Urban Ecosystems

- Water and Watersheds

Short Videos

- Saving a Coral Reef and Fishery (Apo Island, Philippines)

- Community Gardens Reverse Urban Decay (NYC, USA)

- Community Forests Reverse Tropical Deforestation (Thailand)

- Escaping the Pesticide Trap (India)

- Rainwater Harvesting and Groundwater Replenishment (Rajasthan, India)

How Success Works:

- Saving a Coral Reef and Fishery (Apo Island, Philippines)

- Community Gardens Reverse Urban Decay (NYC, USA)

- Community Forests Reverse Tropical Deforestation (Thailand)

- Escaping the Pesticide Trap (India)

- Rainwater Harvesting and Groundwater Replenishment (Rajasthan, India)

Human Ecology:

Principles underlying

EcoTipping Points

Stories from the Middle East

In-depth (based on site visits with extensive interviews)

- Israel/Palestine/Jordan – EcoPeace/Friends of the Earth Middle East and the Good Water Neighbors Project - EcoPeace/Friends of the Earth Middle East restores the environment and improves international relations at the same time.

Capsule (shorter pieces which appear below)

- Iraq – Mesopotamian Marshlands - Formerly desiccated marshlands are brought back to life.

Iraq – Mesopotamian Marshlands

- Author: Regina Gregory

- Posted: November 2011

Source: Nature Iraq

I never imagined the Garden of Eden as a marsh, but according to scholars, the biblical garden was located in the Mesopotamian Marshlands of what is now known as southern Iraq and Iran. This system of interconnected lakes, canals, mudflats, and wetlands between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers once covered an area of nearly 9,000 km2 (3,475 mi2) year round and grew to 20,000 km2 (7,700 mi2) with each spring snowmelt.

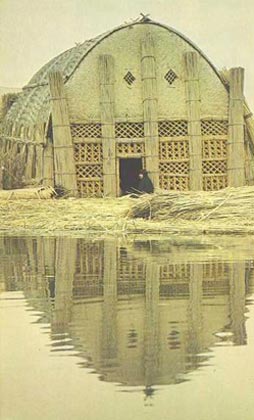

For 5,000 to 7,000 years, the area has been inhabited by Ma’dan tribes (a.k.a. Marsh Arabs), who trace their roots back to the ancient Sumerians and Babylonians. They construct floating islands of reeds on which to put their houses, which are also made of reeds (see photo). Reeds have many other uses as well: mats and baskets (a source of cash income), fodder for water buffalo, fuel for cooking. Crops grown by the Ma’dan include dates, millet, rice, and wheat. Local fish and wildlife provide protein.

Traditional Ma’dan house

Source: iraqupdate.wordpress.com-marsh-arabs

Official statistics are lacking, but it is estimated that in the 1950s the Ma’dan marsh population was 400,000 to 500,000.

Desiccation

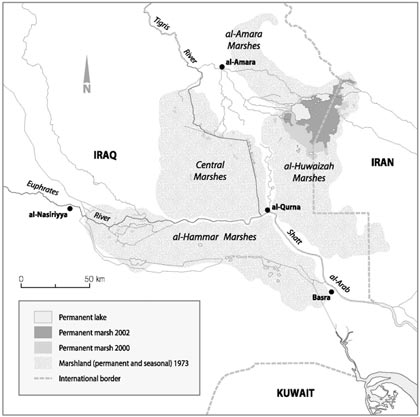

Draining of the Mesopotamian marshlands began with the British in the 1950s. They considered the marshes to be economically useless and a breeding ground for mosquitos, and started a project to direct water from the central Euphrates region into the desert. Later, numerous dams upstream—including those in Turkey, Syria, and Iran—reduced water flow to the marshes to such an extent that the spring snowmelts became barely noticeable. Things got worse under Saddam Hussein. In the 1990s he not only completed the main outfall drain project started by the British, but also constructed a system of canals and embankments which desiccated most of the marshlands. This was for agricultural schemes and oil exploration, but also to drive out the rebellious Marsh Arabs and fugitives who were hiding in the marshes. By 2002 the marshland area had shrunk to just 1,300 km2 (500 mi2)—a decline of more than 85% from its 1973 size (see Map 1). The rest of the area became a salt-crusted desert susceptible to dust storms.

The region’s famed biodiversity was devastated. Besides fish and amphibians, dozens of species of migratory and endemic birds lost their habitat. The smooth-coated otter, bandicoot rat, long-fingered bat, and African darter bird are thought to have become entirely extinct. Marsh desiccation also affected Persian Gulf fisheries: the marshes no longer served as a “sewage treatment plant” or “kidneys” for waters flowing into the Gulf, nor as a spawning ground for migratory fish and shrimp species.

Human population declined as well. The remaining Ma’dan numbered only around 20,000 in 2003. About one-fifth of those who fled went to refugee camps in Iran; some went overseas; the rest were displaced within Iraq.

Map 1. Mesopotamian Marshes, 1973 to 2002

Source: Middleton, Nick. Restoring Eden. Geodate 18(3), 2005.

Rejuvenation

A 2001 report by the United Nations Environment Program, The Mesopotamian Marshlands: Demise of an Ecosystem, brought the tragedy to worldwide attention. In response, a group of Iraqi expatriates—under the leadership of California civil engineer Azzam Alwash—founded the Eden Again Project. With support from the non-profit Iraq Foundation, they assembled a group of international experts in 2002 and began to make a plan for restoring the marshlands.

When Saddam Hussein’s regime was deposed in 2003, things changed rapidly. The Iraqi Ministry of Water Resources created the Center for Restoration of the Iraqi Marshlands, and also that year the New Eden Project, a cooperative project between the Italian and Iraqi governments, began to develop a master plan for sustainable development of the marshlands. In 2004 Alwash founded Nature Iraq, an organization which took over administration of the Eden Again Project and also provides consultation to the Iraqi government and local residents. Beginning in 2005, scientific conferences for the rehabilitation of the Iraqi marshes have been held regularly—covering everything from agriculture and economic enterprises to psychology and veterinary medicine.

In 2007 the Hawizeh Marsh—the only permanent marsh remaining after desiccation—was declared a wetland of international importance under the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands. The Iraq National Marshes and Wetlands Committee was created and a detailed management plan for Hawizeh was drafted in 2008.

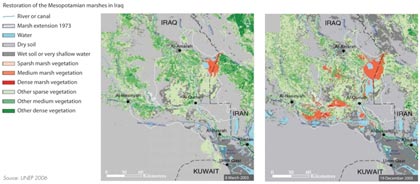

But the people did not wait for the experts and planners. As soon as the regime fell in 2003, they began to break down the embankments Saddam had built, and reflooded large portions of the marshes. In just two years, 60% of the marshes had been reflooded. Long-dormant reeds sprang back to life. Fish, frogs, and birds—even the rare marbled teal, Iraq babbler, and Basra reed warbler—returned. The Marsh Arabs began to return as well; estimated population in 2005 was 60,000.

Map 2 shows the progress of marsh restoration between 2003 and 2005. The Central Marshes made a miraculous recovery, and planning is underway to establish a Mesopotamian Marshland National Park there with the purposes of ecosystem restoration, education and research, and ecotourism. The Abu Zirig marsh to the west, which was the focus of the Italian-sponsored New Eden Project, also did well. But not all the reflooded land fared so well. Some is progressing more slowly and some simply remains as “saltwater desert” because of high soil salinity or impermeable surface. Overall, it is estimated that about 30% of the marshlands have a realistic potential for complete restoration.

Map 2. Mesopotamian Marshes, 2003 to 2005

Source: UNEP

To see the PBS Nature show “Braving Iraq,” go to http://video.pbs.org/video/1634278420