EcoTipping Points

- How do they work?

- Leveraging vicious

cycles to virtuous - Ingredients for success

- Create your own

EcoTipping Points!

Stories by Region

- USA-Canada

- Latin America

- Europe

- Middle East

- South Asia

- Southeast Asia

- East Asia

- Africa

- Oceania-Australia

Stories by Topic

- Agriculture

- Business

- Education

- Energy

- Fisheries

- Forests

- Public Health

- Urban Ecosystems

- Water and Watersheds

Short Videos

- Saving a Coral Reef and Fishery (Apo Island, Philippines)

- Community Gardens Reverse Urban Decay (NYC, USA)

- Community Forests Reverse Tropical Deforestation (Thailand)

- Escaping the Pesticide Trap (India)

- Rainwater Harvesting and Groundwater Replenishment (Rajasthan, India)

How Success Works:

- Saving a Coral Reef and Fishery (Apo Island, Philippines)

- Community Gardens Reverse Urban Decay (NYC, USA)

- Community Forests Reverse Tropical Deforestation (Thailand)

- Escaping the Pesticide Trap (India)

- Rainwater Harvesting and Groundwater Replenishment (Rajasthan, India)

Human Ecology:

Principles underlying

EcoTipping Points

Stories from Oceania

In-depth (based on site visits with extensive interviews)

- We hope to offer detailed stories from Oceania in the near future

Capsule (shorter pieces which appear below)

- Australia - A Sustainable House in the City - A small urban family remodels its 100-year-old house to achieve water and energy self-sufficiency.

- Fiji & Cook Islands - Coastal Fishery Restoration - Traditional no-take reserves and seasonal taboos restore troubled coastal fisheries.

- Guam - The Humåtak Project - A community-based project works to restore Guam's watersheds, coral reefs, and fisheries.

- Vanuatu - Coconut Oil as an Alternative Fuel - In a time of decreasing copra prices and increasing petroleum prices, coconut oil holds promise as a "biodiesel” fuel.

Australia - A Sustainable House in the City

- Author: Eric Schneider

- Posted: March 2009

In 1996, Mike Mobbs, a Sydney environmental lawyer, and his lawyer wife Heather Armstrong set out to renovate their 100-year-old terrace house in the inner-city suburb of Chippendale - to expand their kitchen and make a bit more living space for the two kids. But when they sat down to plan the job they decided to build a house that would be less of a drain on the planet's resources. With a bit of vision, some common sense, and a lot of tenacity, they built what most of us would think impossible... a house in the middle of Australia's biggest city that:

- Collects all its drinking water from the roof

- Generates all of its electricity from the sun

- Processes all of its wastewater, including sewage, on site

Impossible? Outrageously expensive? Here's how they did it...

Mike wanted to collect all of the water the family needed off their roof. They had never been big water users. Even before they renovated, they used just 350 liters of water a day, or about half that of the average Sydney household. But over a year, this still adds up to around 100,000 liters of water.

The house is less than 2 kilometers from Sydney's central business district, sandwiched between two congested inner-city roads (Broadway and Cleveland St.), choked frequently with buses and cars. So with two young kids, Mike and Heather were initially concerned about the quality of the water they'd collect off their roof. They were pleasantly surprised. Today, their drinking water is cleaner than that of most households. The water exiting the other end of the tank is clean enough to be reused in the house as grey water to flush toilets, wash clothes and water the garden, and any excess overflows into a dry reed bed.

The water recycling and sewerage disposal systems in the Chippendale house process around 100,000 liters of sewage each year, preventing it from entering the Pacific Ocean. The organic composting also cuts the local council's waste by several tons. The water recycling and sewage treatment system cost about $11,000, including all of the excavations and the tank, which has the capacity to process waste for nine people.

Annual savings on water and energy bills are around $1,600/yr. Taking into account extra maintenance and gas bills, that works out to an annual saving of about $1,200. The cost-benefit would be greater if neighbors started to use the house's organic waste disposal system, which still has extra capacity.

Michael also estimates the sustainable building costs would be halved if built from scratch.

For more details, click on the links at: http://www.abc.net.au/science/planet/house/special.htm

Fiji & Cook Islands - Coastal Fishery Restoration

- Author: Amanda Suutari

- Posted: May 2005

The decline of the region's fishery (especially the kaikoso, a species of clam important to local subsistence and livelihood) was caused by various factors including overfishing, mangrove destruction, reef blasting, night fishing and foreign fishers.

When villagers of the Veratavou region and a local non-governmental organization got together to find solutions to the problem, they created a list of rules; they banned blasting, gill nets, and mangrove cutting around the lagoon, stopped issuing licenses to foreign fishers, and designated "tabu," or no-take, reserves in designated areas in the lagoons.

Results were immediete and dramatic. The kaikoso increased up to three times in the protected areas, there was a spillover effect into non-protected areas, and other vanished species, including a local delicacy, made reappearances. Residents reported up to 35% increased incomes (some of which goes into a collective trust fund for eight villages, which has been invested into electrification projects). Coastlines are expected to be more resilient to cyclones or other natural disturbances. Community cohesion is increased, and interest in science and tradition among young people has also improved.

Services restored/improved: Food/income, storm protection, cultural heritage values/knowledge systems

This case is similar to what happened in Fiji. The Cook Islands in the South Pacific are populated by indigenous Koutu Nui, whose way of life depends on coastal resources, especially the trochus (their shellfish staple source of subsistence and income).

Similar to Fiji, the Raratonga islanders' fishery was on the decline due to overfishing; fishers were going out further to chase increasingly fewer and less diverse species of seafood; trochus harvests were shrinking.

The elders in Raratonga, alarmed, decided to re-introduce the traditional no-take system known as raui. Unlike Fiji, these are temporary reserves which are instituted or lifted according to season, harvests, and other conditions. Bans on net fishing and night fishing were installed. The local churches, strong social centers for the Koutu Nui people, endorsed the program, which helped strengthen the commitment of villagers. Results were equally dramatic: Trochus populations have exploded, diversity of sea life has rebounded, corals have increased. It has given way to other plans, including bringing local schools to study the life in the lagoon.

Services restored/benefits: food/fiber, ornamental resources (trochus shells), recreation and tourism, education

For more information visit the South Pacific Regional Environment Programme.

Guam – The Humåtak Project

- Author: Regina Gregory

- Posted: September 2013

In the 1970s, Fouha (aka Fu’a) Bay on the southwest shore of Guam was home to a healthy coral reef ecosystem teeming with marine life, according to data from the University of Guam. But in 1988-1992 the Agat-Umatac Road was constructed without environmental mitigation measures, and hundreds of tons of sediment washed into the bay. The nearshore corals were smothered and killed, and the reef became dominated by algae instead of coral. Besides this catastrophic event, ongoing soil erosion and sedimentation are caused by ungulates (deer and pigs) and human activities in the watershed—especially the deer hunters’ practice of burning whole hillsides of forest so the tender new sprouts will attract easy-to-see deers. Some hilltops have become “hardpan,” i.e., all the soil has washed off and no plants can grow.

By 2002, fishing had gotten so bad in Fouha Bay that fishermen in the village of Humåtak (aka Umatac) took their concerns to Mayor Tony Quinata. They believed sedimentation was at the root of the problem. The mayor contacted Robert Richmond, then director of the University of Guam’s Marine Laboratory, for assistance. Dr. Richmond confirmed that sediment is the reef’s primary stressor, and any improvement would require better land management in the bay’s 5-km2 watershed. He assembled a team of researchers from the University of Guam Marine Laboratory, the University of Hawai‘i Social Science Research Institute, and the Australian Institute of Marine Science and obtained funding from the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

In cooperation with the mayor’s planning office, the researchers implemented a collaborative watershed planning project to help the people of Humåtak identify problems and solutions. This was the beginning of the Humåtak Project. As a partnership formed between community members, scientists, and resource agencies, the Humåtak Project became a community-led initiative with numerous partner organizations in the government, the university and high schools, and non-governmental organizations. “What we have is a community that is fully engaged in caring for their ecosystem,” says project coordinator Austin Shelton. Shelton is a marine biology Ph.D. student and a research assistant to Dr. Richmond at the University of Hawaii Marine Laboratory. They continue to provide scientific guidance and coordination for the Humåtak Project community restoration effort under a NOAA grant titled “Science to Conservation: Linking coral reefs, coastal watersheds and their human communities in the Pacific Islands."

The Humåtak Project’s objectives are to:

- have islanders develop true concern for the environment and natural resources;

- reduce sedimentation;

- reestablish fertile land and native forest;

- restore the health of the once-vibrant coral reefs and the abundant nearshore fisheries.

The three main components of the project are: educational outreach, watershed management, and scientific research.

Educational Outreach

Several projects are designed to increase environmental awareness in the community. According to the website (http://humatakproject.org/about-us.html):

The ‘Humåtak Project Educational Outreach Team’ delivers environmental education presentations to classrooms, summer camps, and community groups. Presentations focus on the problem of erosion, which leads to the destruction of native forests, loss of fertile land, contamination of drinking water supplies, sedimentation on coral reefs, and loss of the essential fish habitat.

The Humåtak Project also hosts “Watershed Adventure” field trips, taking participants through the watershed and explaining ecosystem connections. The first of these was in November 2012, when 160 participants—mostly high school marine biology students—hiked from the top of the watershed down to the bay and learned about the ecosystem. Half a dozen more Watershed Adventures have been conducted since then.

Community meetings are held at the village community center to update community members on the progress of initiatives. The Humåtak Project also utilizes social media to build environmental awareness and stay in touch with community members and volunteers. (Humåtak Project on Facebook)

Watershed Management

“The reefs further from shore are still OK,” says Shelton, but “the land is moving into the sea. We want to help the coral move back toward the land.” According to Shelton, once the stressor of sediment is removed, the reef can heal itself through natural processes. Sediment is gradually flushed out of the bay and fish will eat the excessive algae.

Beginning in 9011, the Humåtak Project’s erosion control projects include an innovative combination of reforestation and soil stabilization. In addition to planting tree seedlings, sediment filter socks are installed on the slopes of the watershed. The trees are donated by the Guam Department of Agriculture Forestry Division. The filter socks are created by the Humåtak Project itself, by stuffing mesh stockings with mulch and shredded telephone books. The socks are placed across the flow of water. They reduce erosion in three ways: by slowing water runoff; by trapping sediment; and by stabilizing land, allowing vegetation to reclaim bare soil areas. The photos below show how this method is effective in a very short time.

Source: Micronesia Challenge, May 24, 2013

Labor for these efforts comes from volunteers in the community, Americorps workers, and groups such as the University of Guam Green Interns. The project has hundreds of volunteers, who to date have contributed over 1,500 hours of labor.

To discourage arson by deer hunters, the Humåtak Project gives them alternative deer attractants such as salt licks free of charge, through a partnership with the Guam Coastal Management Program.

Scientific Research

The Humåtak Project is fulfilling a need for long-term, comprehensive data. Two of the Humåtak Project’s most important partners are the Guam Coastal Management Program Long-Term Coral Reef Monitoring Program, and the Guam Community Coral Reef Monitoring Program, which diligently monitor the health of the reef--including coral habitat and associated biological communities (reef fishes, sea stars, sea cucumbers, trochus, and other ecologically and economically important reef organisms)--in hopes of seeing improvement.

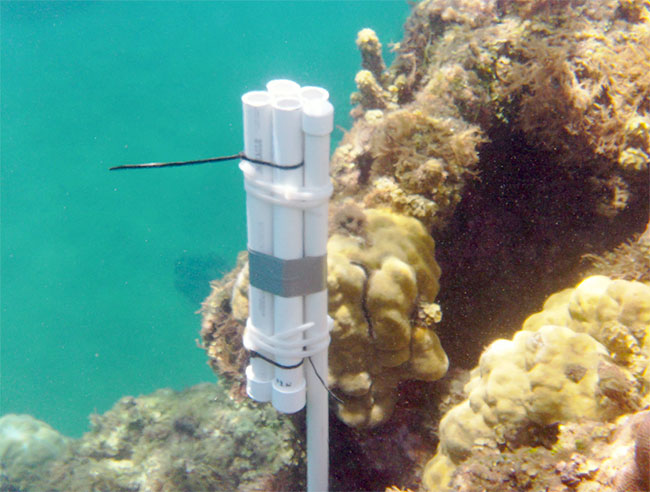

Sedimentation in Fouha Bay is the focus of Austin Shelton’s current research for his Ph.D. in marine biology from the University of Hawai‘i. He has placed sediment traps and multiparameter datasondes throughout the bay to collect data about turbidity, temperature, and salinity. In another year or so the data will be processed and compared to data collected in 2003 and 1978.

Source: Micronesia Challenge, May 24, 2013

The data are expected to be useful in other projects, particularly in improving the science of mitigating for impacts to coral reefs and aquatic resources. Shelton notes that a proposed expansion of the U.S. military on Guam might possibly destroy 70 acres of coral reefs to make way for an aircraft carrier. Federal law requires “compensatory mitigation”—i.e., additional mitigation projects that, together with the proposed project, would result in no net loss of coral reefs. Thus it is important to quantify a correlation between, e.g., the number of trees and filter socks and the acres of coral reefs they might help to rehabilitate.

The Humåtak Project’s slogan is “Reviving Guam, one bay at a time,” and Shelton hopes the model will spread to other watersheds.

Vanuatu - Coconut Oil as an Alternative Fuel

- Author: Amanda Suutari

- Posted: May 2005

This is a pilot project initiated by a local entrepreneur, so this case demonstrates potential rather than results. Similar to the honge tree in India (see South Asia section) it's a variation on the theme of using biodiesel fuel from a local resource with various uses, with projected benefits to rural communities.

Vanuatu is a (relatively) low-income string of 83 islands in the South Pacific, some 1,300 km west of Fiji. 80% of its population is rural. Its main export commodity is coconut, harvested widely here (and in other tropical areas) for its copra (the dried flesh), while its oil is used in food products such as margarine as well as cosmetics, soaps, lotions, etc. The spread of cheaper soy and canola has displaced the coconut market, causing its prices, and therefore incomes in Vanuatu, to fall. Some coconut estates have closed down as a result.

A local entrepreneur named Tony Deamer has successfully developed a way to use coconut fuel in vehicles as an alternative to conventional fuel. Currently Vanuatu is a net importer, with some 9 million US dollars, or 10% of the value of its imports on fuel. Coconut oil could take pressure off the balance-of-payments deficit. Vanuatu is facing serious problems of underemployment and lack of opportunities especially in rural regions. Deamer is also promoting using the opportunities they offer not only for fuel but for other coconut-based products, such as:

- fiber (known as coir) which can be used for mats, ropes, fabrics, brushes, biodegradable packaging (as alternatives to polystyrene), "green" alternatives to peat

- the shells can be used for charcoal for fuel or for purifying water and other liquids (much in the same way Japanese "sumi" is/was used in many common household products)

- oil is useful not only in cars but for cooking, and the residue from pressed oil can be used for animal feed

Like other biodiesels, coconut is cleaner than diesel and burns more slowly. When performance was monitored, the engines running on full or partial coconut oil showed less wear and tear on engines.

A major drawback is that the oil solidifies at 22 degrees celsius; while it is primarily aimed at the domestic market this is not the issue it would be in, say, Canada, but nevertheless temperatures do fall below 22 degrees in Vanuatu, therefore fuel lines need to be fitted with heat exchangers to warm up the fuel, or it must be mixed with conventional diesel. Deamer is currently developing a filtration process that would address this.

Deamer uses coconut oil in five of his own fleet of vehicles for his business, and about 200 minibuses in the city are using some proportion of mixed diesel/coconut fuel in their tanks. There is also experimentation being done on farm machinery.

Other regions of the world are looking to coconut fuel as a source of cheap local fuel, including the Philippines and Nigeria. This illustrates a versatile local resource which offers other products/services/opportunities than biodeisel, and that benefits rural dwellers who are currently off the grid or dependent on imports. But it is still not a very clean energy source, and its large-scale benefits have unresolved questions (such as growing coconut trees would compete with agricultural or forest land).

Potential services/benefits: poverty alleviation, economic opportunities, self-sufficiency, air quality, sense of place