EcoTipping Points

- How do they work?

- Leveraging vicious

cycles to virtuous - Ingredients for success

- Create your own

EcoTipping Points!

Stories by Region

- USA-Canada

- Latin America

- Europe

- Middle East

- South Asia

- Southeast Asia

- East Asia

- Africa

- Oceania-Australia

Stories by Topic

- Agriculture

- Business

- Education

- Energy

- Fisheries

- Forests

- Public Health

- Urban Ecosystems

- Water and Watersheds

Short Videos

- Saving a Coral Reef and Fishery (Apo Island, Philippines)

- Community Gardens Reverse Urban Decay (NYC, USA)

- Community Forests Reverse Tropical Deforestation (Thailand)

- Escaping the Pesticide Trap (India)

- Rainwater Harvesting and Groundwater Replenishment (Rajasthan, India)

How Success Works:

- Saving a Coral Reef and Fishery (Apo Island, Philippines)

- Community Gardens Reverse Urban Decay (NYC, USA)

- Community Forests Reverse Tropical Deforestation (Thailand)

- Escaping the Pesticide Trap (India)

- Rainwater Harvesting and Groundwater Replenishment (Rajasthan, India)

Human Ecology:

Principles underlying

EcoTipping Points

Israel/Palestine/Jordan – EcoPeace/Friends of the Earth Middle East and the Good Water Neighbors Project

- Author: Ted Swagerty

- Editorial contributions: Regina Gregory

- Posted: April 2014

- This story features a Photogallery

Ted Swagerty visited Israel, Palestine and Jordan during September-October 2013 to document the Good Water Neighbors project, which stands as a turning point for cooperation on water and watershed management in three political regions traversed by the Jordan River (Israel, Jordan, and Palestine). Ted interviewed project leaders in all three regions and attended two conferences conducted by the project. Regina Gregory added some information from the foeme.org website and from printed publications that Ted collected during his visit.

The fabled Jordan River is now little more than a sewage canal flowing mostly through a military zone. Over the last 50 years about 96% of the Jordan’s natural flow of 1.3 billion cubic meters has been diverted. The wetland ecosystem of the Lower Jordan has collapsed and over half of its biodiversity has been lost. The Dead Sea is falling by 1 meter per year.

In place of the diverted freshwater, sewage is discharged into the river as well as saline water, agricultural runoff and fish farm effluents. Israel’s Saline Water Carrier flows directly into the Jordan. Palestinian communities struggle with sanitation due to cost and the difficulty of obtaining building permits from the Israeli government. Instead, a system of sewage cesspits and households unconnected to water lines proliferate in the West Bank. Solid waste adds to the problem; almost every waterway is polluted with garbage and debris.

The Mountain and Coastal Aquifers—important drinking water sources—are also endangered by depletion and pollution. Springs that supported agriculture for centuries have started to falter, and wells are running dry. The geology of the area is such that surface water pollution can seep into the groundwater, polluting the aquifer.

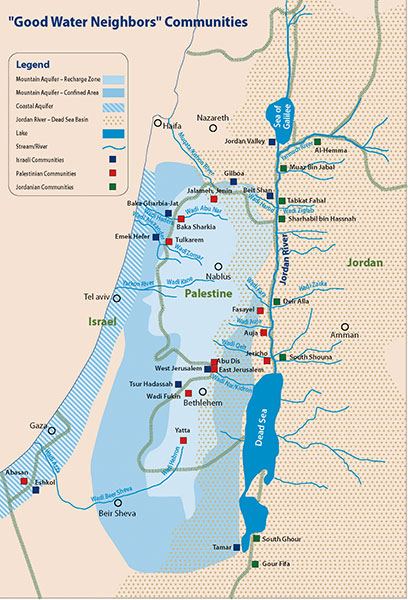

The shared waters of Israel, Palestine and Jordan

Source: FoEME 2010

The root of the problem is conflict, according to EcoPeace/Friends of the Earth Middle East (FoEME). The nations that share the Jordan River watershed raced to capture the greatest possible share of water. About half was taken by Israel and about a quarter each by Syria and Jordan. Palestine, denied access to the river, takes almost nothing. The Palestinian community of Al Auja is an example of the larger problem of water injustice and the steady depletion of ground aquifers. Because the Israeli water company controls the area, including the water resources, they pull out water to the settlements first and the Palestinians second. What's worse is they are depleting the mountain aquifer faster than it can be recharged. The spring in Auja is now only flowing 8 months out of the year instead of all year round. Where almost 90% of residents were farmers in the past, now only 2.5% can farm, and they often use salty water, which leads to poor harvests.

Conflict is also an obstacle to making improvements. The highly sensitive political situation makes international cooperation on shared natural resources especially difficult. But EcoPeace/Friends of the Earth Middle East has made great progress with “environmental peacebuilding”—restoring the environment and improving international relations at the same time.

FoEME is a multinational environmental organization that focuses on peaceful cooperation between Israeli, Palestinian and Jordanian communities to resolve some of the region's most egregious ecological problems. It is an environmental peacebuilding organization that creates functional peaceful relations by focusing on collective ecological interests. By focusing on environmental problems such as water pollution, water injustice, diversion and sewage treatment, communities across borders are talking to one another and building a strong foundation for peace. FoEME has offices in Amman, Jordan; Tel Aviv, Israel; and Bethlehem, Palestine.

Through top-down and bottom-up approaches, FoEME has managed to accomplish a lot in the way this region is thinking about one of its most precious resources and about each other. It creates understanding between the three nations by mobilizing communities to focus on tangible environmental goals instead of waiting for a political settlement.

Philosophy

The philosophy of FoEME and by extension modern theory of peacebuilding is quite simple. The point is to focus on a very real issue that both parties have a common interest in and from that common interest, establish a dialogue and a shared goal from which both parties can benefit. At a recent conference promoting FoEME’s peacebuilding, Lord John Alderice provided the example of the fisheries department that was shared between Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland. From the fisheries, a vested interest on both sides, they were willing to make a deal about sharing its resource. The fisheries proved to be the common denominator or the common setting to start peaceful cooperation.

FoEME aims to do that with Israeli, Palestinian and Jordanian communities with its focus on water and the larger environmental health of the region as the common meeting point for any meaningful peaceful cooperation.

FoEME understands that their goals of environmental rehabilitation, water justice and peaceful coexistence will not be accomplished in a day or even ten years. They are working with very large time lines. They realize that they are advocating something quite radical and to accomplish their goals will take a long time.

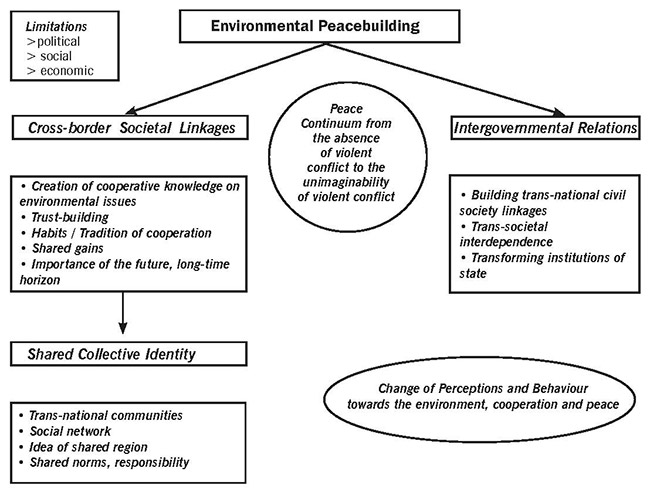

They realize that any sustainable and meaningful peace will have to be desired from the general population on the ground level as well as the government administrative level. FoEME is effective at environmental peacebuilding by having a dualistic approach of top-down and bottom-up advocacy. The diagram below shows a conceptual view of the elements of environmental peacebuilding.

Focal points in the concept of Environmental Peacebuilding

Source: Harari and Roseman 2008, p. 14

History

FoEME, originally known as EcoPeace, started around the time of the Oslo Peace Negotiations in 1994. According to the Israeli director, Gidon Bromberg, the organization came together as they noticed a huge inattention to pressing environmental matters within the peace accords themselves. There was some agreement reached on water sharing and allocation but not a broad, long-term evaluation of the region's environmental problems and certainly no focus on remedies. EcoPeace was greatly disturbed with the large development plans of new infrastructure and hotels. As Mira Edelstein, Foreign Media Officer of FoEME, said in an interview, the environment was taking a backseat in the peace negotiations.

For most of the 1990s, EcoPeace, which consisted of representatives from Israel, Palestine, Jordan and Egypt, was mostly focusing on crafting top-down policy reports for regional organizations and government decision makers. Their initial concern was to be a watchdog organization of what they found were unsustainable development plans accompanying the future peace process. The first report that EcoPeace completed was about the Dead Sea. Following reports were focused on the Jordan River and the Red Sea. They convened conferences for decision makers, organizations and government officials to focus on the immense amount of environmental degradation as well as to draw attention to the opportunity of sustainable development.

From 1998 to 2000, FoEME was in a great transition period that reflected the new caustic political environment that enveloped the Middle East. The deterioration of the peace process and the increase of violence had soured their efforts at making the peace agreements more environmentally sustainable. Moreover, as an organization that was associated with the peace process, it was associated with its failures and negative connotations. Any Arab/Israeli cooperation was seen as traitorous, collaborative and serving the interests of the other side. FoEME had to reinvent itself to reflect the changed political environment.

The organization continued to advocate greater cooperation to protect shared natural resources. It continued to write a series of papers advocating greater environmental cooperation in the middle- to long-term interest of the entire region. However, the staff knew they needed to reach out to communities on a grassroots level to keep their message relevant amongst a violent atmosphere. They developed a bottom-up strategy to complement the top-down work.

The Good Water Neighbors (GWN) Project was born in 2001 as one of FoEME’s grassroots strategies. The GWN program aimed to teach Israeli, Palestinian and Jordanian communities about their shared water resources with bordering communities in hopes of building greater understanding and eventually a peaceful atmosphere. However, as the funding was secured from an EU peace grant, it was revoked with the advent of the Second Intifada in 2001. All peacebuilding efforts seemed hopeless, the fund holders declared. It took all three directors to fly to Brussels personally to assure them they had 11 communities who were willing to participate in the GWN program. The original group consisted of one Jordanian, five Israeli and five Palestinian communities that all shared common water resources.

To initially engage the communities to participate in the GWN program, a local representative of FoEME would approach the municipality first and ask if they would be interested. After the municipality gave its approval, FoEME started a series of environmental education programs in schools as after school programs. Lessons were generally interactive, hands on activities to get students aware of the environmental issues facing their community. Students learned about water pollution and conservation while making water experiments, cleaning up a spring, and going on field trips.

As FoEME's environmental education succeeded in schools, it initiated community education by providing local experts (such as Parks Department officials) to lecture to adult audiences in the community about water scarcity, conservation and pollution, as well as informative lectures about the surrounding geography, ecology and the shared water bodies.

To continue the grassroots strategy, FoEME finally engaged mayors of the municipalities and encouraged them to cooperate with neighboring cross-border communities. Around the same time, FoEME initiated cross-border visits between Israelis, Jordanians and Palestinians of students, adults, farmers and city officials. These visits would consist of touring water infrastructure such as wastewater treatment plants and pipelines. The environmental focus on water kept the cross-border meetings focused and on track. Focusing on water issues provides commonality to engage in discussion and cooperation. Peacebuilding is virtually not talked about. It is understood that the organization is trying to build cross border relationships but, Mira said, that “people just want to talk about water.” Moreover, “There was always a follow-up and a next time. I think that's what makes us different,” said Mira.

The communities of Wadi Fukin and Tzur Hadassah--located on opposite sides of the Green Line (the border between Israel and Palestine)—were exemplary in their activism. They tackled the issue of sewage from the Israeli settlement of Beitar Illit flowing onto Palestinian farmland with the FoEME Israeli staff reporting the problem to the relevant Israeli authorities. Wadi Fukin and Tzur Hadassah also took a proactive stance in challenging plans forconstruction of a separation barrier between their two communities, as well as future neighborhood expansion, even taking the matter to the Israeli Housing Ministry.

Current Projects

FoEME meets its goals of better environmental stewardship and peacebuilding by engaging in a “top-down” and “bottom-up” strategic advocacy approach. The top-down strategy includes tactics such as:

- Sponsoring independent ecological and economic research studies and publications

- Drafting policy for decision makers, donors, and various regional actors that draw on evidence from independent and comprehensive research studies

- Advocating to European Union and American elected officials to create more awareness of the ecological problems facing the region

- International speaking tours

- Organizing international conferences where policy experts and decision makers can share their thoughts on the region's water and larger environmental issues

- Leveraging funds to construct more water infrastructure

The top-down strategy is challenging to witness but as the directors each have experience in policy and local politics in their own countries, they understand the necessity of addressing decision makers, donors, government officials, leaders of industries and other influential regional actors.

FoEME leverages funds to pay for studies that provide hard evidence that environmental rehabilitation and water conservation are not only desired but an absolute necessity. They have done numerous studies on the ecological crises affecting the area such as the shrinking of the Dead Sea, depleting groundwater, and the destruction of the Jordan River as well resolutions to solve these dire ecological problems. They raised funds and are developing a master plan for the Jordan River Valley and have completed a comprehensive study about the economic benefits of a rehabilitated Jordan River. Other publications include papers regarding an alternative Water Accord, the Mountain Aquifer Study and an estimate of how climate change will affect the region's water resources.

From these research papers, FoEME is able to craft consistent policy with supportive evidence in favor of a healthy environment and shared water resources. The Master Plan for the Lower Jordan Valley was based on ecological and environmental assessments. The Israeli government has a Master Plan of its own, for its section of the River. FoEME hopes that Jordan and the Palestinian Authority will adopt the suggestions in FoEME's NGO Master Plan currently being developed.

FoEME’s recommendations for rehabilitation of the Jordan River are:

- The return of at least 400 million cubic meters (mcm) of freshwater into the river every year—220 mcm from Israel, 100 mcm from Syria, and 90 mcm from Jordan

- Right of access and right to a fair share of water for Palestine

- At least one flood per year of 100 m3/second for a 24-hour period

- Maintaining salinity below 750 milligrams per liter

- National policies to manage demand for water in the agricultural and domestic sectors

FoEME appears many times to argue their position in many government bodies and hearings. A representative of FoEME was present at a Knisset hearing in September 2010 to speak about the ecological crisis of the Jordan River. They did the same at the Water Committee in the Jordanian Parliament in February of 2011. FoEME also advocates to elected officials outside of the region. In 2007, a US Senate resolution passed to support the rehabilitation of the Jordan River. In 2010, the European Parliament passed a similar resolution.

They also organize an annual conference usually centered on the Good Water Neighbors Project inviting policy specialists, bureaucrats and elected officials to talk about the possibility and the necessity to come up with a sustainable, cooperative water policy within the region. (See notes, Appendix A.)

FoEME is able to leverage millions of dollars through special grants, earmarks and donations to construct sorely needed water infrastructure such as sewage treatment plants, more advanced irrigation systems and the rehabilitation of springs, streams and rivers. Generally, elected officials like to be associated with such infrastructure projects because it provides a positive accomplishment to their constituencies.

Complimentary to top-down advocacy, FoEME believes it to be imperative to engage communities on a grassroots level. FoEME's bottom-up approach includes tactics such as:

- Teaching environmental awareness in public schools in Palestine, Israel and Jordan and installing water-saving devices in each participating school

- Organizing cross-cultural youth environmental education programs

- Giving community lectures to adults about environmental problems affecting their community and arranging cross-border trips

- Creating eco-centers as a place for environmental education and eco-tourism

- Through the Good Water Neighbors Program Israeli, Palestinian and Jordanian communities are working together to address water pollution and needs i.e. the case of Wadi Fukin and Tzur Hadassah

- Creating “Neighbors’ Paths” that highlight shared watersheds between Palestinian, Israeli and Jordanian communities

- Through the Jordan River Rehabilitation campaign, FoEME is engaging with faith-based communities to realize the importance of saving the Jordan River by creating literature that connects religion to the significance of the rehabilitation campaign

- Taking groups of Israelis, Palestinians, and Jordanians as well as tourists from other countries to the Peace Island in hopes of spreading the idea of a peace park shared between Jordan and Israel

- Leveraging funds to community projects and water treatment plants

- Creating a mayors’ network and organizing the “Big Jump” event, a commitment to share water resources between communities symbolized by jumping in the Jordan River

Good Water Neighbors

The Good Water Neighbors (GWN) project is a huge program that generates a lot of positive change in the realm of environmental peacemaking. The GWN changes people's perceptions of how they see the conflict. When a person meets people from the “other side,” he or she begins to realize that they are very similar to his or herself. Through the GWN, members of each border community are able to stay fairly connected with the other side, building a platform to resolve common environmental problems and land use issues. Municipalities are much more in touch with the management of local resources.

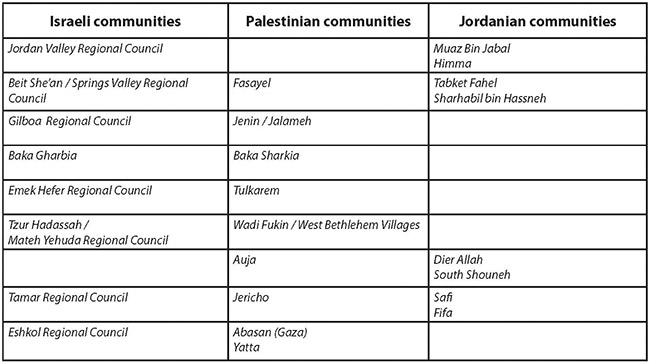

GWN has grown to include 28 partnering communities (see map), paired up according to shared cross-border water resources as shown horizontally in the table below. A detailed description of each GWN community and its environmental concerns is available online.

Source: FoEME 2013a

Good Water Neighbor communities, arranged according to shared water resources

Source: FoEME 2013a

As mentioned earlier, the GWN strategy is to engage first youth, then adults, then mayors. The result is a series of cooperative infrastructure projects that improve water quantity and quality.

Eco-education

Environmental education in affiliated community schools is a backbone of how the grassroots organization of FoEME got started. They teach about the dangers of water pollution and how open sewage cesspits can spread disease. The organization creates awareness in students about the need to conserve water any way they can by not letting the water run or by taking shorter showers. A large part of the curriculum focuses on the natural ecology of the region and spends time doing creative exercises with students in art, music and drama about the need for greater environmental stewardship. The students use the FoEME Water Care curriculum which includes a Student Resource Book, a Teacher’s Guide, and a web page. The major topics addressed by the materials include water resources, water use, water pollution, water management for conservation, and water for the future, all from a regional perspective. The materials were prepared jointly by Jordanian, Israeli, and Palestinian educational writers and are available in English, Arabic, and Hebrew.

At the GWN conference (see Appendix A), participants broke out into small groups to sample the curriculum. Group members were told to draw what came to their minds when they imagine no borders. Each participant took two minutes of drawing what images came to their mind when they thought of a world without borders. The leader of each group then asked each participant to share the meaning of their drawing to the group. Discussions naturally generate from this exercise about cooperative and equitable use of resources.

The Water Trustees program is an environmental education program for Israeli, Jordanian and Palestinian students aged 12-16 in the GWN communities. It is important that they are peers and in the same age group. The Water Trustees tour parts of the Dead Sea and areas near their own shared communities. They are taught extensively about water shortage, water pollution, and uncontrolled sewage waste. One youth group initiated a petition calling for action on the water situation, and now all the Water Trustees develop petitions specific to their cross-border issues. Language seems to be the main obstacle for real relationship building between the students. Another issue of the program is that these cross-cultural retreats are very meaningful at the time, but FoEME staff expressed a fear that these experiences are compartmentalized and put away in the back of students' minds, never really taking what they've learned into their community. That is also a criticism of other cross-cultural organizations such as Seeds for Peace. This one experience of a retreat is really meaningful for the students because they get to interact with students their own age from the “other side.” However, if the retreat is only once a year, students seem to treasure the experience when it is going on but not take that experience to their families and communities. “They don't live it,” as one coordinator commented. The Water Trustees program aims to change that by engaging in the students in a continuous year-long program with a field trip at least once a month.

An exciting new project involving Water Trustees and local municipal staff is the Community Geographic Information System (CGIS) project, which uses advanced GIS technology to map environmental hazards.

"Ecofacilities" were also incorporated into the GWN youth program. In each school involved in the project, the principal, teachers, students and even the janitor help design a wise-water building model. This includes, for example, catching rainwater falling on the roof and reusing water from drinking fountains and air conditioners for flushing toilets and watering the school garden. Many are able to cut their water consumption by one third, and serve an example for other public buildings. In 2007 constructed wetlands were introduced at many schools for wastewater treatment.

For adults, FoEME arranges educational lectures and forums. The topics range from the dangers of untreated sewage and wastewater to the importance of conserving water and the natural ecology of the area. Farmers have benefited immensely, Mira said, as these lectures quickly formed a core group of interested individuals who participated in cross-border visits. Israeli farmers visited Jordan to see what agriculture was like there, Mira mentioned, as well as Palestinians and Jordanians coming to Israel to learn about better water conservation techniques and more efficient ways of irrigation.

Cross-border trails or Neighbors’ Paths is another way the GWN project educates the public and mobilizes grassroots support for better environmental stewardship. The idea is to create hiking trails that display shared resources such as springs, streams, rivers and woods as well as sights that are harmful to the environment of the region (sewage and waste negligence, garbage dumps, the Green Line Wall, etc.) First proposed by the community of Tzur Hadassah, each GWN community now has a Neighbor's Path or is in the process of planning one. It is a great way to demonstrate the connection that the border communities have.

Mayors Network

The GWN project has resulted in a series of Memorandums of Understanding signed by the mayors of the paired neighboring communities. The mayors also formed a network that meets regularly at the regional and sub-regional level to discuss common concerns. Being in a position between the grassroots and top-level leaders, they are able to not only cooperate on infrastructure projects, but also make political statements. They are proof that peaceful cooperation is in fact possible.

The “Big Jump” event—a day when the mayors come together to jump in the clean part of the Jordan River (or in its nearby tributary the Yarmouk) is a way to demonstrate their commitments to shared interest in water and other environmental issues. It is a fantastic way of creating public awareness and excitement within grassroots communities about water issues. Not only that, but the mayors seem to benefit from the media and community attention. From a marketing perspective FoEME also benefits by having pictures of mayors from Palestine, Jordan and Israel together holding hands and their own nations’ flags. That picture is indeed worth a thousand words because in one image it demonstrates FoEME's goals of peacebuilding through the environment. FoEME joined the European “Big Jump” event and they have used it very effectively to communicate their message.

Good Water Neighbors mayors at the 2010 Big Jump event

Source: foeme.org website

Infrastructure

GWN hired a planner in each community and launched a process of participatory planning, or community-based problem solving. Each set of cross-border communities identifies common environmental problems and shared solutions. This results in an annual list of “Priority Initiatives.” The most recent of these (FoEME 2013a) identifies 18 priority initiatives—8 in the aquifers area and 10 in the Lower Jordan River/Dead Sea area:

A. Mountain Aquifer, Coastal Aquifer and Coastal Stream

- Creating a municipal cross-border Hadera/Wadi Abu Naar stream committee

- Preventing pollution of the Hebron/Be’er Sheva/Besor Stream by Israeli sources

- Protecting the natural springs of the Judean/Jerusalem Hills

- Design and supervision of Abasan Wastewater network

- Increasing agricultural production and enhancing economic opportunities for Batter and the West Bethlehem Villages

- Rehabilitation of Falafel’s springs

- Rehabilitation of the sewage network in Tulkarem and construction of a new network in unserved areas of the city

- Rehabilitation of the freshwater supply network in Yatta

B. Lower Jordan River/Dead Sea Basin

- Stabilizing the Dead Sea through advancing a combination of alternative measures

- Rehabilitating the Jordan River

- Promoting regional educational perspectives on the demise of the Dead Sea and Jordan River system

- Treating wastewater in Gilboa and Springs Valley Regional Councils

- Rehabilitation of Auja’s spring and its agricultural canal

- Construction of a small-scale water harvesting system for the area of Jericho

- Al Hemma open canals

- Rehabilitation of Deir Alla dump site

- Overcoming the housefly problem in South Ghour

- Sewage collection and cesspits monitoring for the communities of Muaz Bin Jabal, Tabkat Fahal and Sharhabil Bin Hassnah

The amount of money that FoEME is able to leverage is quite impressive. This adds to the draw of being a part of the GWN network and also why communities want to belong so badly. FoEME leverages funds to support GWN communities' water infrastructural needs, especially Palestinian and Jordanian communities. With a physical improvement to their lives and to the wider community, FoEME transforms the hardest critic into a supporter. In its history of operation, FoEME has raised over US$520 million for investments in GWN communities. US$124 million were spent in the last two years alone—US$10.5 million for sanitation, US$77.5 million for industrial pollution, and US$36 million for stream rehabilitation and parks.

Eco-Centers

The construction and development of eco-centers seems to be a very effective educational tool that FoEME employs to change the minds of people living in border communities as well as visiting tourists. The eco-center works as a hotel and a demonstrative classroom that teaches locals and visitors about the merits of saving water and recycling materials.

Guests can stay at the comfortable accommodations Al Auja Eco-Center provides. They often receive custom tours in which the center’s staff demonstrate building structures out of mud and recycled materials. I stayed at Al Auja Eco-Center which I found very enjoyable. We toured the grounds in which they demonstrate building structures out of mud and recycled materials. There were several stations where students can sit and learn about pollution and water scarcity. There is also a garden and a constructed wetland. Generally, visiting students help the eco-center in some way such as building a mud building or doing maintenance to existing structures. The Al Auja Eco-Center is the middle of the Al Auja village, providing a safe environment for children to play after school. Visitors to Al Auja often are given a tour of the surrounding area and especially the damaged spring nearby. One immediately gets the sense of the total domination that Israel has over Palestinians and their water. Palestinian towns are dusty and dry in contrast to an Israeli settlement that is growing lush green agricultural produce not more than a few kilometers away.

An outdoor classroom at the Al Auja Eco-Center

Photo: Ted Swagerty

The eco-center in Jordan, Sharhabil Bin Hassneh, is a fantastic area where Jordanians can come enjoy the pleasures of nature while learning about the environmental problems that affect the region. Abed, one of the founders of the Jordanian eco-center, said that in the last year alone seventeen children died from playing in fast-moving canals and culverts. That says to him that Jordanians want a place where they can recreate, but have no place to do it. The eco-center was built near a dam and reservoir. There are numerous walking trails to several points of the surrounding area. The eco-center is much larger than that of Al Auja but shares a lot of the same qualities as primarily an educational center. It boasts compost toilets, constructed wetlands, swimming pools, a pond, and a picnic area. There are affordable cabins where guests can stay for a price of $25 to $50, depending on the size of the group.

All eco-centers accomplish their goals of demonstrating sustainable living and educating the public on environmental issues and water scarcity as well as provide a safe place where community members are welcome to use their grounds to rest and relax. They also serve as an enterprise for eco-tourism with the eventual goal of being financially self-sufficient.

Save the Jordan

The latest effort in FoEME's Jordan River rehabilitation campaign is a fascinating grassroots component to tap yet another facet of society in the region: faith-based communities. The Save the Jordan Conference was convened to draw representatives and leaders from the three Abrahamic faiths—Judaism, Christianity and Islam. They want to motivate faith-based communities because the Jordan is a river that is sacred to all three religions. Moreover, by mobilizing religious communities they will have another ally in their effort to gain a political relevance. With new found constituencies in religious communities they will put further pressure on elected officials and decision makers to rehabilitate the Jordan River.

Similar to the other facets of the organization, focusing on the rehabilitation of the Jordan gives a common platform that faith-based communities can unite around, building trust and understanding while restoring a badly damaged ecosystem.

In order to better reach out to faith-based communities, FoEME has created a set of literature that ties the importance of the Jordan River and its health to scripture from each religion's holy texts. There is a Jewish sourcebook (FoEME 2013g) in both Hebrew and English in hopes of drawing Jews from within Israel and other parts of the world (namely North America) to the issue of restoring the Jordan River. There is a Christian sourcebook (FoEME 2013e) that is currently only in English but they have plans to translate it into Spanish, French, German and Italian. The Islam sourcebook (FoEME 2013f) is in Arabic and English. There is also a Save the Jordan “briefing” booklet for each religion (FoEME 2013b, c, d). All of these publications include FoEME’s recommendations for rehabilitating the Lower Jordan River.

At the conference during a breakout session, the attendees were asked to separate into three groups of Jews, Christians and Muslims and give constructive criticism about the source books in question. Most of the groups approved of the idea of the source books but they provided some positive criticism.

The Christian group didn't have much issue with the book itself but talked about the need for a larger, captivating physical experience to further motivate folks to go back home (whether home be in the region or abroad) and advocate for the restoration of the Jordan River. They suggested that FoEME employ a series of songs, poems and stories while taking Christian groups to the Jordan River to create that “change in spirit.” They also suggested that visitors want to do something when they are aware of the problem. They could do some work, preferably physical labor, so that the visitors could come away with a feeling of accomplishment and pride. That feeling is important, they agreed, because it is that sense of pride and feeling they assisted with something larger than themselves that inspires them to talk about the Jordan River campaign in their home communities.

The Jewish group was very analytical. They chose to read the source book as a group, stopping periodically to comment or to constructively criticize. They found that some texts chosen for the Jewish source book had references that seemed too “Christian” and wouldn’t connect with other Jewish audiences. They were concerned that the source book was just reaching out to the reform sect of Judaism and not all aspects of Judaic culture were being targeted. Most of the group agreed that the use of scripture from Joshua and his narrative of crossing the Jordan slaying his enemies ran counter to the peaceful cooperative spirit that the campaign and FoEME in general embodies.

The Islamic group excitedly discussed a variety of improvements but generally really liked the source book. They suggested that FoEME create a mini-toolkit for Muslim children or a child appropriate source book. They wanted their book to be in more languages than just Arabic and English. They felt it was appropriate to have the source book translated in Urdu, Indonesian and Malaysian dialects to name a few. Finally, they felt that the current political history should be addressed. One member suggested that they contextualize the history and suffering of the Palestinian people with passages in the Qur’an relating to water in hopes to connect the resurrection of the Jordan River with Palestinian statehood.

For further detail, see the conference notes in Appendix B.

The conference ended with religious leaders and representatives from all three Abrahamic religions signing the Covenant for the Jordan River. The Covenant, a document that FoEME created, is an agreement of understanding and commitment to the revitalization of the Jordan. The faith-based representatives were asked to sign to commit themselves and their religious communities to honor the sacred Jordan River by working to restore the river to its natural state.

A professor of Islamic studies signs the Covenant after Rabbi Awraham. Two Syrian Orthodox bishops and the directors of FoEME look on in the background

Photo: Ted Swagerty

Peace Island

The Peace Island, near Kibbutz Ashdod Yakov, is another way FoEME arouses action on the grassroots level. They organize groups of Israelis, Palestinians and Jordanians to visit the Peace Island and invite them to imagine a larger cross-border Peace Park shared between Jordan and Israel. The park has a short but sad history. It is the site of one of the first hydroelectric dams in the area that was designed and built by a Russian Jew and administered by Arabs. The plant ceased operations in 1948 with the outbreak of war. It still serves as a reminder that cooperation is possible. The same area was the site of another act of violence when a Jordanian soldier left his post and shot seven Israeli high school girls.

Hagai Oz, whom I interviewed extensively, takes regular tours of Israelis, Palestinians, Jordanians and other tourists from outside the region to the Peace Island. He talks about the political history, the ecology and the potential of a larger cross-border peace park. FoEME holds that the creation of a larger, shared peace park would be an economic boon and a large lure for tourists on their way to Tiberius. I accompanied a group of German tourists to visit the Island. Hagai estimated that he probably leads more than 100 tours a year. “If there is this much interest in a peace park before it has even started, you can imagine how great it will be when we actually make a Peace Park,” Hagai expressed excitedly.

Hagai Oz shows what has become of the Jordan River to a German tour group visiting the Peace Island

Photo: Ted Swagerty

Funding

One of the things Michael Schwartz, the head of FoEME's fundraising department, made clear is that FoEME makes excellent use of all of the assets in the area. For instance, there is a lot of aid money that goes to Palestine and they are able to apply for those grants because they can say they are a Palestinian organization, which they are. They are simultaneously an Israeli, Jordanian and Palestinian organization and that's what makes them so successful in the way of funding. There are a lot of Jewish-American organizations that they are able to get funding from, as well as development organizations such as the UN and other organizations that fund the NGO sector in Jordan.

Likewise, because it is an environmental peacebuilding organization, it is able to use that dualism of environment and peacebuilding as an additional funding asset. FoEME can apply for grants that are focused on environmental projects in the Middle East as well as grants that focus on peacebuilding. They are so effective at this, Michael admitted, that they have had fund holders to actually call them and ask how they should write this next grant so they can apply for it and get it.

Another large chunk of their funding is from government aid and development organizations. The US Agency for International Development, the German Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit, the Swedish International Development Agency, and EU Aid all make large contributions to FoEME's operations. Environmental organizations such as the Goldman Fund, Global Nature Fund and the Osprey Foundation also contribute to environmental studies and research.

In short, the organization is a magnet for funding because of its multinational nature and its dualistic approach in advocating its goals of environmental peacebuilding.

Challenges

When one takes into account this large of a strategy, one begins to realize just how immense the water problems that plague the region really are. All of these projects seem to be the tip of the iceberg. FoEME is making a lot of progress raising awareness about water issues as well creating cross-border committees that monitor their area's water use, but there is still a lot of work to be done. It seems FoEME knows that. It’s just the start.

FoEME’s size and diversity is definitely an asset, yet it can also be a weakness at times. With such a large organization (over 100 people working for FoEME in total), one of the main challenges is to find enough funds to just keep the organization open and with the lights on, let alone leveraging enough funds to complete the priority initiatives or sponsor conferences, etc. Their grant writing department is hard at work applying for grants to keep the organization going and to complete their goals of the GWN and the Jordan River Rehabilitation Project. Currently, funds to maintain and funds to grow continue to be the main challenge.

During the second Intifada there was a real danger to the staff and people who worked with the organization. All three directors have faced harsh criticism from their own cultures about working with the “other side” and betraying their own people. Munqeth, the Jordanian director, was shot at from a passing car when he was on his way home from work. Nader Khatib and all of his Palestinian staff have faced huge social and cultural challenges by being castigated in their communities as normalizing the occupation of Palestine. Each of the Palestinian staff members has had to face a certain degree of social criticism from families and friends. For some, it has mostly subsided. For others, it continues. A Jordanian staff member admitted that her family stops talking to her about her work because they don't want to hear about it. They politely avoid the subject and talk of other things.

How most staff members have defended themselves from ridicule by being associated with the other side is as unique as each person. Elizabeth Ya'ari said of her coworkers that, “we are not normalizing because we are changing things. If we were normalizing, we wouldn't try to be changing how people act towards each other.”

When asked if it was difficult to work for the organization at times of increased violence, most staff members replied with increased determination. Fadi, the Palestinian staff member at Al Auja, admitted that to live under occupation is incredibly hard. He told me a heart wrenching story about his cousin being shot by an Israeli sniper after he had just said goodbye to him several minutes before. However, Fadi said that he never felt angry towards any of the Israeli staff members of FoEME because he knows that they are working just as hard as he is to create understanding between the two sides. During the same period of violence, Shamu, a charming Palestinian staff member, boasted how she would always call her Israeli friends to ask if they were OK if she heard about a bus bombing. They in turn would call her frequently during the siege of Bethlehem in 2003.

Another challenge is the dilemma that illegal Israeli settlements have an important impact on the water regime, but they are not officially recognized by FoEME, and no Palestinians are interested in cooperating with illegal Israeli settlements.

Another psychological challenge is the huge cynicism that is pervasive in the region. At the local level, residents of cross-border communities are suspicious of each others’ motives. And because there has been such a tragic history of violence and a failed peace process, any talk of a peaceful settlement is generally treated with a high degree of skepticism in Israel, Palestine and Jordan. Most people think it is very difficult if not impossible.

An interesting discussion that demonstrated this problem of cynicism occurred between several Israelis and Americans at the Save the Jordan conference. When asked about cynicism, an Israeli rabbi acknowledged that there is a lot on both sides of the conflict. Steven Holbin, a cultural therapist from New York, added that visitors from abroad may expect a peaceful settlement tomorrow. It is not that easy, the rabbi said, but he continues to have hope. He added, “What makes FoEME different than other organizations is that they do work to achieve peace instead of just talking about it.”

“A Measure of Progress”

FoEME’s three “Save the Jordan” briefings (FoEME 2013b, 2013c, 2013d) report the following progress:

In the last 3 years we have seen the first signs of progress in the struggle to revive the river.

Responding to years of advocacy, national governments and municipalities are now working to prevent the dumping or leaking of untreated sewage into the river. New treatment plants are in development in Jordanian, Israeli, and Palestinian communities throughout the Jordan Valley. If this commitment is maintained, half a century of using the Jordan as a sewage canal can now be brought to an end.

2013 also saw the first release of clean water into the Jordan River in 49 years. The Israeli Water Authority has agreed to allocate 3 million cubic meters of fresh water every year from the Sea of Galilee (also known as Lake Kinneret or Lake Tiberius) to help revive the river. This sets an important precedent for future allocations, but it falls far short of FoEME’s recommendation that Israel release 220mcm of water, and Jordan a further 90mcm, as part of an international effort to rehabilitate the Jordan.

Future

As for FoEME's future plans, it seems that the main thrust will be on continuing its current projects. I talked to Mira Edelstein at length about the future of the organization and she said she had really no way of knowing. Every five years, they create a five-year plan and where they want the organization to be. Every three years, they take some time to evaluate their five-year plan and make proper adjustments. She thinks they will return to an effort in growing grassroots support within their GWN network of communities. They have plans to adopt two more communities, Palestinian and Israeli, making the sum total to be 30 communities. Mira thought that the communities have not received as much attention recently as they should. She predicted there will be an effort to refocus their efforts on these communities.

The organization will undoubtedly continue to leverage funding to complete 18 Priority GWN projects which will require a significant amount of time and money. Each individual project generally costs US$50,000 to US$5,000,000. One of the biggest priority projects is the rehabilitation of the Jordan River. Although successful steps have been made it still seems they have a way to go to get the project completed.

It will be interesting to see how they continue their grassroots campaign for the rehabilitation of the Lower Jordan River. Now that they have initiated a campaign to engage communities of all three Abramhamic faiths it will be interesting to see how they will channel those constituencies to make an impact. I am sure there will continue to be a lot of dialogue between FoEME and religious leaders. I expect them to host trips to the Jordan as well as more events to popularize the idea of rehabilitation by emphasizing the cultural/religious significance the Jordan has. So far, however, there are not any concrete plans of another event drawing on religious groups.

They would like to see the emergence of a master plan for the Jordan River Valley drawn up by the Jordanian government and the Palestinian Authority. This is important to the overall strategy for FoEME's plans in the Jordan River Valley. Master plans submitted by all three nations are crucial for FoEME to create an inclusive ecological Master Plan for the entire region of the Jordan River watershed.

References

FoEME. 2010. Why Cooperate Over Water? Shared Waters of Palestine, Israel and Jordan: Cross-border crises and the need for trans-national solutions. Download available at: http://foeme.org/uploads/12893974031~%5E$%5E~Why_Cooperate_Over_Water.pdf

FoEME. 2012. Take Me over the Jordan: Concept Document to Rehabilitate, Promote Prosperity, and Help Bring Peace to the Lower Jordan River Valley. Download available at: http://foeme.org/uploads/13480625611~%5E$%5E~Take_Me_Over_the_Jordan_2012_WEB.pdf

FoEME. 2013a. Community Based Problem Solving on Water Issues: Cross-Border “Priority Initiatives” of the Good Water Neighbors Project. Download available at: http://foeme.org/uploads/13841891381~%5E$%5E~Community_Based_Problem_Solving_on_Water_Issues_2013.pdf

FoEME. 2013b. River out of Eden: A briefing for Christian educators and community leaders. Download available at: http://foeme.org/uploads/13807071641~%5E$%5E~ChristianBrief.pdf

FoEME. 2013c. River out of Eden: A briefing for Jewish educators and community leaders. Download available at: http://foeme.org/uploads/13807085311~%5E$%5E~JewishBrief.pdf

FoEME. 2013d. River out of Eden: A briefing for Muslim educators and community leaders. Download available at: http://foeme.org/uploads/13823512970~%5E$%5E~BriefIslam.pdf

FoEME. 2013e. Water, Ecology, and the Jordan River in the Christian Tradition: A sourcebook for educators and community leaders. Download available at: http://foeme.org/uploads/13832203161~%5E$%5E~Christian_WEB.pdf

FoEME. 2013f. Water, Ecology, and the Jordan River in Islam: A sourcebook for educators and community leaders. Download available at: http://foeme.org/uploads/13832207801~%5E$%5E~Islam_WEB.pdf

FoEME. 2013g. Water, Ecology, and the Jordan River in the Jewish Tradition: A sourcebook for educators and community leaders. Download available at: http://foeme.org/uploads/13832206131~%5E$%5E~Judaism_WEB.pdf

Harari, Nicole and Jesse Roseman. 2008. Environmental Peacebuilding Theory and Practice: A Case Study of the Good Water Neighbors project and In Depth Analysis of the Wadi Fukin/Tzur Hadassah Communities. Amman, Bethlehem, and Tel Aviv: EcoPeace/Friends of the Earth Middle East. Website http://foeme.org/uploads/publications_publ93_1.pdf

Jueejat, Fadi. n.d. Political conflict, social injustice and environmental degradation in the Jordan Valley. PowerPoint presentation.

Appendix A. Notes on the Good Water Neighbors Conference, November 13-14, 2013

Mark Singleton- Deputy head of Mission

Office of the Quartet, Jerusalem

The Quartet focuses on water issues and the Palestinian Economic Initiative

West Bank: Chronic source of water problems and depletion

Gaza: overdrawing of marine aquifer

Bold steps for implementation:

- enacting a series water use regulatory laws

- public and private partnerships

- minimizing water utilities

Water and energy: There needs to be a stronger electric utility to power to Gaza desalination.

Conclusion: for policy changes of this magnitude, it will be difficult and will take time. These changes are an issue of self interest for both peoples.

Saad Abu Hammour- Secretary General

Jordan Valley Authority, Jordan

He supports the idea of multinational cooperation although he fully supports the Red-Dead Canal.

Khalil Ghabiesh- Head of West Bank Water Department

In Article 40 of the 1994 Peace Treaty, Palestinians have reservations

In agreements there was a policy of what is ours is ours and what's yours is yours

“Water policy was never defined well. We need to work on this. What was allocated in 1994 is largely nonexistent now.”

Yata, for instance, is a large Palestinian city but cannot connect to the Israeli water system.

We need a new mechanism to mediate between sides and technical aspects.

Oded Eran- Senior Research Associate at the Institute National Security Studies

Ambassador (retired) to Jordan and the European Union

At Camp David, during the Peace negotiations, there was one team dealing with political issues and another team at Emmitsburg to deal with water.

We should focus on water as the first issue. Cooperation is very possible. We really need to be aware of the alternative reality if we can't come to an agreement.

The cost of desalination is the cost of energy. We need to look at water as a method to facilitate a comprehensive peace agreement.

Frode Mauring- Special Representative of the Program of Assistance to the Palestinian People

UNDP

Water is a basic right but on the ground not a reality. In Gaza, 95% of people are without clean drinking water. Palestine is lacking a huge amount of water management infrastructure.

The issue is urgent and complex.

Amir Peretz- Minister of Environment, Israel

He sees a direct relationship between quality of life and quality of environment. There are no national borders in the environment. Winds move from west to east. Water moves from east to west. Everything is shared! If the air is polluted, it will go to the east. If the water is polluted it will move to the west.

I had two formative experiences when I was a child. One memory was of waking up in the middle of the night after a bomb blast and soldiers’ talking to his parents making sure everyone was OK and conducting an investigation. The other memory was of all of the mothers in my village, Jews and Arabs, shopping together. I chose to reflect on the latter, positive memory.

We cannot be distracted or derailed by small acts of violence like the death of a soldier. We have to be a friend of the earth and a person for peace.

Panel: Living up to our Responsibility for the Dead Sea

Saad Abu Hammour: There are efforts already to stop the destruction of the Dead Sea such as government efforts, UNESCO Title etc. I can say that the government of Jordan is deeply concerned about this issue because the Dead Sea provides a great source of tourist dollars to Jordan.

Avishai Braverman- Member of Israeli Parliament: There were several projects that the World Bank proposed to stop the drying of the Dead Sea including a northern canal and the Red-Dead Sea Conduit but getting the LJR rehabilitated would save the Dead Sea.

The difference between mice and men is the culture of memory. Men remember and keep working towards a solution.

Noam Goldstein- Senior Vice President of Meshivim Division, Israeli Chemicals:

Industry is easier to blame than agriculture. We haven't increased our evaporation or pumping since the 1990s.

The resource is owned by the Israeli public no arguments about that. Royalty payments to government have increased and we are seeing our profits decrease.

Moderator: Should there be a fee to use water?

Saad Abu Hammour: I understand that the business has a right to exist but it is still making a tremendous profit.

Goldstein: To say that nobody knows the facts is not true. I don't think we need to apologize for making money. We are taxed very heavily as high as 40-50%

Dov Litvinoff- Head of the Tamar Regional Council, Israel:

The problem is not just industry which about 30% of the problem. 70% of the problem is the people that drink from the Dead Sea and the agriculture in the area.

Mr. Nader Khatib- FoEME Palestinian Director:

The West Bank side of the Dead Sea has a large amount of sink holes. “We see a sink hole every day.”

Panel: The experience of Peace building in troubled areas

Dajana Berisha, Exec. Director, Forum for Civic Initiatives, Kosovo:

Kosovo became independent state following the disintegration of Yugoslavia in December of 2008. Her organization creates a forum of discussion.

“Power comes with local people”

John Alderice, Member of the House of Lords, UK:

There is a danger in thinking: civil society is good. Governments and politicians are bad. In reality we need the whole ecosystem of decision makers and grassroots organizations. The great strength of NGOs is their focus on one issue versus the politician having to balance his time and his constituents amongst many issues. It’s very important to respect the strengths and weaknesses of governments and NGOs.

Panel: How can we save the Jordan?

Dov Hanin- Member of the Israeli Parliament:

There were two geographical problems at the Peace negotiations: Jerusalem and the Jordan River. We need to think about the river as an asset and a unifying force. We don't want the river to be just a military boundary.

Ram Aviram (Ret. Ambassador):

The lower Jordan River Rehabilitation Master Plan will set a benchmark that hopefully the other parties will respond to.

Yossi Vardi- Head of the Jordan Valley Regional Council, Israel :

10 MCM is already flowing into the Jordan and 30 MCM will flow eventually by the middle of 2014.

Ali Al Aqli- Head of the Muaz Bin Jabal, Regional Council, Jordan:

Peace doesn't mean that we have to agree on everything. We cannot divide between the situation and the politicians' aspirations. I'm excited about the idea of the Peace Park. It will generate jobs and be a great fruit of the peace process.

Hassan Al Jermy- Mayor of Zabaidat, Palestine:

I was born on the banks of the river. The area used to be fertile with fish now we’re not allowed to get to the river. 17 NGOs are involved in the Lower Jordan River Valley. That number means that we have a large, significant crisis on our hands but I have confidence that we will find a solution together.

Panel: Cross-Border Environmental Education

Amy Lipman Avizohar, Lead Environmental Education Coordinator at FoEME:

The objective is to draw students to the topic of water through engaging activities and curriculum. They have a textbook. They encourage their students to think critically, research, to be tolerant, to participate in civil groups.

Four Basic Principles for Water Education of FoEME:

- no borders

- a right not a commodity

- sustainability

- peaceful solutions

Dalia Feniq- Education Coordinator, Israel:

Important to focus on regional issues in Israeli education system. They address the social-political issues that are connected with ecological issues.

Rashed Al Sa'ed- Technical advisor at Global Environmental Studies:

Why environmental education?

- Local and regional regulations

- food security and political situation

- partnerships in the region

Palestinian perspectives:

- promotion of capacity build and training programs

- enhancement of research programs

- higher education in water and environmental studies

- recent academic programs with regional environmental focus

- Research and Development environmental studies with an emphasis on waste water treatment and waste management.

*There has never been more of a critical need for Palestinian ecologists as the ecological and political crisis worsens. Israeli settlers burnt and uprooted more than 2000 olive trees planted in 1905 in 2013.

Mohammed Nawsrah- Former School Principle, FoEME Community Coordinator:

He started as a coordinator in 2002. He brought 8 students to Israel for environmental education program. His advice to any environmental educator is to not give up. He had a hard time convincing parents to let their children go to Israel but he continued and is very proud of his achievement.

Appendix B. Notes on the Save the Jordan Conference, November 10-12, 2013

Opening Poem (Telling of the creation of the River from the River's perspective)

Munqeth Mehyar- Chairman and Director of FoEME (Jordan)

“Us coming together is not necessarily about loving each other. It’s about coming together to solve a crisis. We cannot do that without appealing to three countries. We cannot do that without appealing to the three Abrahamic religions... We need your leadership in the three Abrahamic faiths to move on.”

“Our goal is the full restoration of the Jordan River of 1.3 million MCM (million cubic meters).”

Helena Rietz, Swedish Ambassador to Jordan

Her grandfather traveled Palestine in the 1920s and kept a journal. He said, “I arrived in Jericho to a welcome surprise. God is providing the sun.”

After touring the Jordan Valley, he wrote, “This is God's paradise on Earth. There is no comparison.”

Secretary General of the Jordan Valley Authority (Jordan)

There are many reasons for immense pollution: salinization, diversion, sewage, fish farm waste water, etc.

Master plans are being formed and will be revealed in 2014.

Jerry White- Deputy Assistant Secretary of State, Bureau of conflict and stabilization operations

“I'm happy to be here hanging out with friends in low places.” (A Dead Sea quip)

“84% people in the world believe there is a greater force beyond themselves.”

“Resilience is created together through religious communities businesses and individual cooperation.”

FoEME's secret to success:

- multiple countries/troubled areas

- top down/bottom up advocacy

- eco parks, grey water and gardens in schools

Human beings' mission is to return the earth to as it was. As we found it! A world rich in biodiversity and abundant resources. A world full of truth, justice and equality.

Religious group breakout sessions (discussion of sourcebooks (FoEME 2013e, f, g))

Christian criticism of sourcebooks:

- People want to do something preferably something physical (i.e. pick up trash or plant native species or help local farmers).

- In order for a change of spirit there needs to be songs, poems, literature/stories that inspire and draw more significance to the restoration of the Jordan River.

- Trips for Christian visitors should be very comprehensive. Combining eco-education/values, river ecology, scriptural study of the river, prayer, worship, physical labor, writing letters, tweet, and other internet action (donations, online petitions etc.)

Conversation in the Christian circle:

A careful balance must be struck between practical political solutions and spiritual inspiration. That should be the goal of mobilizing Christian faith groups to rally behind the restoration of the Jordan River.

The importance of these books comes when FoEME successfully mobilizes faith groups half way around the world for the restoration of a river that many Christians haven't even seen. The challenge lies in getting Christians from around the world excited about saving a river they have little to no physical relationship with. “An issue we need to face is what makes this river so important from any other river. Or to put another way, out of the thousand rivers that are damaged and in need of restoration in Christian countries, what makes this one so important?” - Doug Thorpe, Professor at Seattle Pacific University

Western Christians have the luxury to be somewhat removed and not to suffer like some Palestinian Christians. They can't go to the Jordan to be baptized. A large effort should be instigated from leaders of our Western Christian culture to get them access to the river. Publicize that effort and that political reality to draw more attention to the injustice in area with the significance of the river.

There needs to be a huge stress and focus on curriculum in schools because there are hardly any Christian communities on the banks of the Jordan River.

There should be a considerable effort of reeducating Christians that may feel they know what's going on in the area. For instance, to questions like “Should we be helping Palestinians? I thought they hate America.” A clear and concise summary of political realities and FoEME's goal of restoration should be emphasized. “It’s about the river, stupid.” -Gerry White, US State Department

Mary Alexander, the moderator, summed up the group's suggestions in a quick presentation:

Recommendations for revision:

- Add additional information on the contemporary political reality of the Jordan and how engaging this issue can build peace and water justice.

- Strengthen the tourist dimension by storytelling, meeting people along the Jordan, and activities for tourist participation to contribute to the rehabilitation of the Jordan River.

- Be more specific about the background on the river's demise, the need for access and efforts underway to rehabilitate it.

- More details on how to transform communities to champions of the river.

- Add a brief description/ history of religious communities and traditions in the area.

Jewish criticism of sourcebooks:

- Some texts sounding too 'Christian' by way of using too much of a determined, triumphant narrative. There were a lot of concerns about how most Jews will not relate to this sort of style of scripture.

- The first criticism led to a general concern that this source book will only reach certain aspects of Judaic culture. A large part of the group felt that the source book appealed to the most liberal aspects of Judaic culture and not to more conservative or orthodox sects of Judaism. The source book should resolve this by drawing on unifying values of Judaism with the importance of the river in their history and why the restoration is imperative.

- The source book should avoid scripture from Joshua. Due to the content of Joshua, which is essentially a long narrative of how the Israelites triumphed over their enemies, the group recommends the source book should avoid these stories despite having many references to the Jordan River. The group felt that this narrative is contrary to FoEME's larger aim in building peace.

Rachel Haverlock, the moderator, presented the Jewish group's criticism:

Goals:

- Raise awareness to all aspects of Judaic culture

- Gain involvement from communities around the world

- Determine who the target audience is.

Comments:

Start need to be adjusted:

- Far less use of Joshua

- How to address the Jewish audience specifically as Jews or to focus on the quality of people who are Jewish

Content:

- More use and incorporation of Deuteronomy, Genesis, rabbinic, secular and modern texts.

- Inclusions of songs and poems

- relate the story to individuals today

- use the story of Ruth crossing the Jordan

- use of sources for prayer

Questions:

What to do with the book? Internationally vs. locally?

To start with the bible or rabbinic sources? Our vision vs. current sources?

Islamic criticism of sourcebooks:

- The group advocated for a 'kid friendly' sourcebook that contained the same basic information but more appropriate for children. Parents want to teach their children the importance of the river in Islam's history and think that this book for children could be really helpful.

- They also suggest that the source book be translated into several other common languages of Islamic countries such as Indonesia, Burma, Malaysia, Turkey and Iran.

- The group felt it necessary to touch on the recent political history of the region and of the river. Address the question of “why can't Palestinians go and see the Jordan River?” in an honest, respectful manner.

- The toolkit should be specific to each region especially for Palestinians

- A special emphasis on the value of natural resources and a healthy ecosystem.

Shahab Hussein, the moderator, summed up the session:

What is the importance of the rehabilitation of the river? Economically? Socially?

How to disseminate the materials? Mini-toolkit for the youth as well as introducing the material as curriculum into schools.

The group suggested creating a forum of educators to look at the curriculum and how this can be introduced in the region and internationally.

- More interfaith dialogue in the region.

- Seminars in colleges and universities

- TV program about the Jordan River

- Frequent visits (Muslim and interfaith) to the Jordan River

Partnering in Good Faith

Husna Ahmed- Green Pilgrimage Network

“Greening the haj” and other pilgrimages.

Todd Deatherage- Exec Director and Founder of Telos Group

Telos works with Evangelical Christian groups to work with the Mideast and the rehabilitation.

Elisa Moed- Travelujah (Travel + Hallelujah = travelujah)

Travelujah is a tour and travel company that offers pilgrimage, political, sustainability, food and culture tours.

Yahya Hendi- Muslim Chaplain at Georgetown University

“The Qur'an says, there is a balanced earth that we are a part of. Our earth is our mother. No one is his right mind would hurt his mother.”

He suggests:

- A caravan of different religious leaders visiting different communities to talk about the health of the river.

- Engage communities of faith by music, poetry and writing

- Publish an interfaith book about the Jordan River

Partnering in Good Faith #2 (Panel)

Mohammad Al Hourani – Director of licensing Department of the Palestinian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities

“If we truly love this land which is so contested, why are we polluting it and putting rubbish in it?”

“In Palestine, come walk in the footsteps of prophets to heal our environment and our relationship with our neighbors.”

Einat Kramer- Founder and Director, Teva Ivri (Hebrew Nature)

Her organization is promoting the idea of the sabbatical year. In ancient times, every seven years the Israelites would let their fields go fallow. Teva Ivri wants to revive that idea by encouraging Israeli faith based groups to participate in a year volunteering and sustainability

Khalid Kareem- Media and Islamic Thinker

“All three faiths of Abraham should not only empower ourselves as a tool to heal this river and the region's political situation along the way but we should also empower our women and children!”