EcoTipping Points

- How do they work?

- Leveraging vicious

cycles to virtuous - Ingredients for success

- Create your own

EcoTipping Points!

Stories by Region

- USA-Canada

- Latin America

- Europe

- Middle East

- South Asia

- Southeast Asia

- East Asia

- Africa

- Oceania-Australia

Stories by Topic

- Agriculture

- Business

- Education

- Energy

- Fisheries

- Forests

- Public Health

- Urban Ecosystems

- Water and Watersheds

Short Videos

- Saving a Coral Reef and Fishery (Apo Island, Philippines)

- Community Gardens Reverse Urban Decay (NYC, USA)

- Community Forests Reverse Tropical Deforestation (Thailand)

- Escaping the Pesticide Trap (India)

- Rainwater Harvesting and Groundwater Replenishment (Rajasthan, India)

How Success Works:

- Saving a Coral Reef and Fishery (Apo Island, Philippines)

- Community Gardens Reverse Urban Decay (NYC, USA)

- Community Forests Reverse Tropical Deforestation (Thailand)

- Escaping the Pesticide Trap (India)

- Rainwater Harvesting and Groundwater Replenishment (Rajasthan, India)

Human Ecology:

Principles underlying

EcoTipping Points

Marine Sanctuary: Restoring a Coral-Reef Fishery (Apo Island, Philippines)

- Author: Gerry Marten

- Posted: June 2005

- Site visit assistance and editorial contributions: Ann Marten

- This story is excerpted from Environmental Tipping Points: A New Paradigm for Restoring Ecological Security, Journal of Policy Studies (Japan), No.20 (July 2005), pages 75-87

- Short video of this story (7 minutes)

- Educational materials: “How Success Works” lesson for this case (study plan, narratives of various lengths, photos, PowerPoints, student worksheets, teacher keys)

- This story features a Photogallery

Contents of this page

- The narrative (immediately below)

- Photos for the narrative

- Ingredients for success in this story

- Feedback analysis for this story (vicious cycles and virtuous cycles)

- An update on this story (January 2010) - “Replication of Apo Island’s Example to Other Villages in the Philippines” by Portia Nillos-Kleiven

In a remote fishing village in the Philippine archipelago, coastal fishers responded to falling fish stocks by working harder to catch them. The combination of dynamite, longer workdays, and more advanced gear caused stocks to fall faster. On the edge of crisis, this small community decided to create a no-take marine sanctuary on 10% of its coral-reef fishing grounds. This initiative sparked a renaissance of not only their fishery, but also their cherished way of life.

Apo Island provides a relatively simple but very real case study for exploring how EcoTipping Points work in practice. Apo is a small island (78 hectares), 9 kilometers from the coast of Negros in the Philippine archipelago. The island has 145 households and a resident population of 710 people. Almost all the men on the island are fishermen. The main fishing grounds are in the area surrounding the island to a distance of roughly 500 meters, an area with extensive coral reefs and reaching a water depth of about 60 meters. Fishermen use small, paddle-driven outrigger canoes, though a few fishermen (particularly younger ones) have outboard motors on their canoes. The main fishing methods are hook and line, gill nets, and bamboo fish traps.

Apo Island’s “negative tip” started about forty years ago. Before then, there was a stable fishery with ample harvest to support fishermen and their families. During the years following World War II the growing human population and increasing fishing pressure made the fishery increasingly vulnerable to unsustainable fishing. The “negative tip” came with the introduction of four destructive fishing methods to the Philippines:

- Dynamite fishing, which started with explosives left over from World War II and gained momentum by the 1960s;

- Muro-ami (from Japan). Fish are chased into nets by pounding on coral with rocks.

- Cyanide, introduced during the 1970s for the aquarium fish trade. Aquarium fish are no longer collected in this region, but cyanide remained.

- Small-mesh nets. Worldwide marketing of newly developed nylon nets brought small-mesh beach seines and other small-mesh nets to the region in the 1970s.

Dynamite, cyanide, muro-ami, and small-mesh nets are more effective than traditional Filipino fishing methods, but they are seriously detrimental to the sustainability of the fishery. Not only do they make overfishing and immature fish harvesting easier, they also damage fishing habitat. These fishing methods have been illegal since regulations were imposed in the early 1980s. The Philippine Coast Guard and National Police are responsible for enforcing fishing regulations, but their vast areas of jurisdiction have made it virtually impossible for these agencies to stop destructive fishing.

The introduction of destructive fishing methods set in motion a vicious cycle of declining fish stocks and greater use of destructive methods to compensate for deteriorating fishing conditions. Damage to the coral reef habitat is now extensive throughout much of the Philippines, and fish stocks are generally low.

Fish stocks in the most degraded areas are down to 5-10% of what they were 50 years ago. Though catches in degraded areas are not sufficient to support a fisherman full-time, the fishery continues to be depressed by a large number of fishermen, many of them part-time and many using illegal fishing methods that they consider the only practical way to catch fish under these conditions. The problem is exacerbated by illegal encroachment of larger commercial fishing boats with gear such as purse seines and ring nets wherever enforcement is lax and nearshore fishing conditions are good enough to make encroachment worthwhile.

The prelude to the positive tip for Apo Island began in 1974 when Dr. Angel Alcala (director of the marine laboratory at Silliman University in Dumaguete City) and Oslob municipality (Cebu) initiated a small marine sanctuary, the region's first, at uninhabited Sumilon Island (about 50 km from Apo). Dr. Alcala and some of his colleagues at Silliman University visited Apo Island In 1979 to explain how a marine sanctuary could help to reverse the decline in their fishery, a decline that had become obvious to everyone. By that time, fish stocks on the Apo Island fishing grounds had declined so much that fishermen were compelled to spend much of their time traveling as far as 10 km from the island to seek more favorable fishing conditions.

Dr. Alcala took some of the fishermen to see the marine sanctuary at Sumilon Island, which by then was teeming with fish. They were able to see how the sanctuary could serve as a nursery to stock the surrounding area, but they were not completely convinced. Marine sanctuaries were not part of Philippine fisheries tradition. After three years of dialogue between Silliman University staff and Apo Island fishermen, 14 families decided to establish a no-fishing marine sanctuary on the island. A minority of families was able to do it because the barangay captain (local government leader) supported the idea.

The positive tip for Apo Island came with actual establishment of a marine sanctuary in 1982. The fishermen selected an area along 450 meters of shoreline and extending 500 meters from shore as the sanctuary site - slightly less than 10% of the fishing grounds around the island. The sanctuary area had high quality coral but few fish. It required only one person watching from the beach to ensure that no one fished inside the sanctuary, guard duty rotating among the participating families. Fish numbers and sizes started to increase in the sanctuary, and "spillover" of fish from the sanctuary to the surrounding marine ecosystem led to higher fish catches around the periphery, eventually to a distance of several hundred meters. In 1985 all island families decided to support the sanctuary and make it legally binding through the local municipal government.

When the fishermen saw what happened in and around the sanctuary, they concluded that fishing restrictions over the island's entire fishing grounds should be able to increase fish numbers there as well. With technical support from a coastal resource management organization, the fishermen set up a Marine Management Committee and formulated regulations against destructive fishing and encroachment of fishermen from other areas on their fishing grounds. They established a local "marine guard" (bantay dagat) consisting of village volunteers to police the fishing grounds. It was no longer necessary to guard the sanctuary per se because everyone accepted its status as a no-fishing zone. The main task of the marine guards today is to check boats that enter their fishing grounds from other areas. They do not seem to worry about Apo Island fishermen because sustainable fishing has become an integral part of the island culture.

Although available data do not allow a precise comparison of current fish stocks and catches on the Apo Island fishing grounds with fish stocks and catches when the sanctuary was established, the data indicate that catch-per-unit-effort more than tripled by the mid-1990s and has not changed much since then (Russ et al. 2004). The larger and commercially more valuable fish (e.g., surgeon fish and jacks) increased more slowly and are in fact still increasing. This scenario is confirmed by the fishermen's subjective impression of what has happened.

Interestingly, the total catch by island fishermen is about the same as 23 years ago when the sanctuary began. This is because the fishermen have responded to the increase in fish stocks by reducing their effort instead of catching more fish. Fishermen no longer must travel long distances to fish elsewhere. Fishing is good enough right around the island. A few hours of work each day provides food for the family and enough cash income for necessities. The fishermen worked long hours before. Now they enjoy more leisure time. If they wish, they can use some of the extra time for other income generating activities such as transporting materials or people between the island and the mainland. The most prominent reason for earning extra money is to fund higher education for their children.

The striking abundance and diversity of fish and other marine animals (e.g., turtles and sea snakes) around the island have attracted coral reef tourism (Cadiz and Calumpong 2000). The island has two small hotels and a dive shop, which employ several dozen island residents. In addition, diving tour boats come daily from the nearby mainland. A few island households take tourists as boarders, and some of the women have tourist related jobs such as catering for the hotels or hawking Apo Island T-shirts. The island government collects a snorkeling/diving fee, which has been used to finance a diesel generator that supplies electricity to every house in the island's main village during the evening. The tourist fees have also financed substantial improvements for the island's elementary school, garbage collection for disposal at a landfill on the mainland, and improvements in water supply.

Tourist revenue has also provided family income and "scholarships" (from one of the island hotel owners) to finance more than half the island's children to attend high school on the adjacent mainland, and many continue to university. Almost all university graduates and many high school graduates stay on the mainland with a job that allows them to send money to their family back on the island. A few return for professional work on the island such as elementary school teacher, and some aspire to return to contribute to the island's health services, governance, or marine ecosystem management. Remittances from family members living off-island are used mainly for private infrastructure such as house improvements. Many people who live away from the island live close enough for frequent visits to their family on the island.

Apo Island has served as a model for fishing communities on the adjacent mainlands of Negros and Cebu. The head of Apo Island's local government visits other fishing villages to explain the sanctuary, and people from other villages visit Apo to see what it's all about. In 1994 the Apo Island example, and the fact that Dr. Alcala was Minister of Natural Resources, stimulated the Philippine government to establish a national marine sanctuary program that now has about 700 sanctuaries nationwide. Not all are functioning as well as they should, but many seem to be on the same path as Apo (see Replication of Apo Island’s Example to Other Villages in the Philippines). While the national network has provided benefits, it has also reduced the autonomy of Apo’s local government and increased national government interference in management of the sanctuary and the use of revenues from tourist fees.

The Apo Island story is not a fairy tale. I visited Apo Island, I talked to island residents, and everyone told me the same story. They firmly believe that the sanctuary saved their island. The story is documented by scientific publications that include 25 years of monitoring the island fishery and ecological conditions in the sanctuary. The following publications provide an overview: Russ and Alcala (1996), Russ and Alcala (1998), Russ and Alcala (1999), Alcala (2001, p. 73-84), Maypa et al. (2002), Raymundo and Maypa (2003), Russ and Alcala (2004), Russ et al. (2004), Alcala et al. (2005), Raymundo and White (2005).

Apo Island is not perfect. There are personal conflicts, political factions, complaints about government, and many other things typical of human society around the world. People on the island are not particularly affluent. Houses do not have piped water; residents must collect water from faucets strategically placed around the village. Medical services on the island are limited, though doctors can be reached with a half-hour boat ride to the mainland. Many feel that the economic benefits of tourism, which go mainly to the hotel owners, should be distributed more evenly. While participation in the national sanctuary program has reinforced the status of the Apo Island sanctuary and provided networking benefits, it also means island fishermen no longer have complete control of sanctuary management or funds that come from diving and snorkeling fees.

As tourism has increased, concern has grown about the impact of snorkeling and diving on the sanctuary and the fishery (Reboton and Calumpong 2003). The island government has instituted restrictions on the number of tourists in the sanctuary to limit damage to coral there. Fishermen have complained that divers scare fish away from where they are fishing and sometimes damage their fish traps or release fish from the traps. As a consequence, divers are not allowed to swim within 50 meters of fishing activities and the prime fishing area is completely off limits to divers. Some island inhabitants are not satisfied with enforcement of these restrictions, and dialogue continues about what should be done to protect the marine ecosystem from damage by tourism.

But overall, there is a conspicuous atmosphere of well being and satisfaction with quality of life on the island. This is not because the island inhabitants are ignorant or inertial. They value their quality of life and the quality of the island's marine ecosystem, and they want to keep it that way. Their experience with the sanctuary has taught them an important lesson. It is necessary to change some things by community action in order to keep other very important things the same. They are committed to keeping their island's fishing grounds sustainable.

Twenty years ago the island inhabitants changed the way they managed their fishing activities. Now they need to make some changes in the size of their families. Everyone agrees that the island's increasing human population is a serious threat to its future. A family planning program was initiated two years ago, and contraceptives are readily available at a small community-operated family planning center. Most families are using them. Young people, even elementary school children, readily express their intention to have a small family. Immigration of people who are not descended from Apo Island families is not allowed.

The sanctuary has changed the way that people on the island view their world. The fishermen say that before the sanctuary their strategy was to fish a place with destructive methods until it was no longer worth fishing and then move to a new place that was not yet degraded. Now they are committed to keeping one place, their island's fishing grounds, sustainable. Before, they expected government agencies responsible for enforcing fishing regulations to do so and complained when it didn't happen. Now they enforce their own regulations themselves. This spirit of local initiative has extended to developing the island's infrastructure and assuring that island children get the education they need for a decent future. Organization for fisheries management has stimulated the community to organize in other ways as well – particularly women's groups. The island has a locally operated women's credit union and a women's association for selling souvenirs to tourists.

Apo Island’s marine sanctuary is sacred to the people there. They say it saved their coral-reef ecosystem, their fishery, and their cherished way of life. The sanctuary was an EcoTipping Point – a “lever” that reversed decline and set in motion a course of restoration and sustainability.

Acknowledgments

Angel Alcala, Alan White, Laurie Raymundo, Aileen Maypa, and Mario Pascobello provided information for the Apo Island story. Portia Nillos helped in numerous ways during my visit to Apo Island.

References

- Alcala, A. C. 2001. Marine reserves in the Philippines: historical development, effects and influence on marine conservation policy. Bookmark, Makati City, Philippines.

- Cadiz, P. L., and H. P. Calumpong. 2000. Analysis of revenues from ecotourism in Apo Island, Negros Oriental, Philippines. Proceedings of 9th International Coral Reef Symposium (Bali, Indonesia, 23-27 October 2000), Volume 2:771-774.

- Liberty’s Community Based Lodge and Paul’s Community Diving School, Apo Island.

- Maypa, A.P., G. R. Russ, A. C. Alcala, and H. P. Calumpong. 2002. Long-term trends in yield and catch rates of the coral reef fishery at Apo Island, central Philippines. Marine Freshwater Research 53:207-213.

- Raymundo, L. J., and A. P. Maypa. 2003. Chapter 14. Apo Island marine sanctuary, Dauin, Negros Oriental. Pages 61-65 in Philippine coral reefs through time. The Marine Science Institute, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Philippines.

- Raymundo, L. J., and A. T. White. 2005. 50 years of scientific contributions of the Apo Island experience: a review. Silliman Journal (50th Anniversary Issue), Silliman University, Dumaguete, Philippines.

- Reboton, C., and H. P. Calumpong. 2003. Coral damage caused by divers/snorkelers in Apo Island marine sanctuary, Dauin, Negros Oriental, Philippines. Philippine Scientist 40:177-190.

- Russ, G. R., and A. C. Alcala. 1996. Do marine reserves export adult fish biomass? Evidence from Apo Island, central Philippines. Marine Ecology Progress Series 132:1-9.

- Russ, G. R., A. C. Alcala. 1998. Natural fishing experiments in marine reserves 1983-1993: community and tropic responses. Coral Reefs 17:383-397.

- Russ, G. R., and A. C. Alcala. 1999. Management histories of Sumilon and Apo marine reserves, Philippines, and their influence on national marine resource policy. Coral Reefs 18:307-319.

- Russ, G. R., and A. C. Alcala. 2004. Marine reserves: long-term protection is required for full recovery of predatory fish populations. Oecologia 138:622-627.

- Russ, G. R., A. C. Alcala, A.P. Maypa, H. P. Calumpong, and A. T. White. 2004. Marine reserve benefits local fisheries. Ecological Applications 14:597-606.

Apo Island coral-reef fishermen use canoes for their work.

Fish on Apo Island's coral reef.

Location of the marine sanctuary at Apo Island.

Apo Island's marine sanctuary seen from the beach.

Reef fish before establishing the sanctuary and 10 years afterwards.

With tourism, some Apo Islanders developed small business such as selling souvenir T-shirts.

Apo Island's tourist strip: a small hotel (on the side of the hill), dive shop (dark building on the left), and church (white building on the right).

Apo's children "tipping" to a sustainable future. Apo Island has become a place for children to thrive.

Ingredients for Success – The Apo Island Story

- Author: Gerry Marten

We can draw the following interconnected lessons about EcoTipping Points from the Apo Island story:

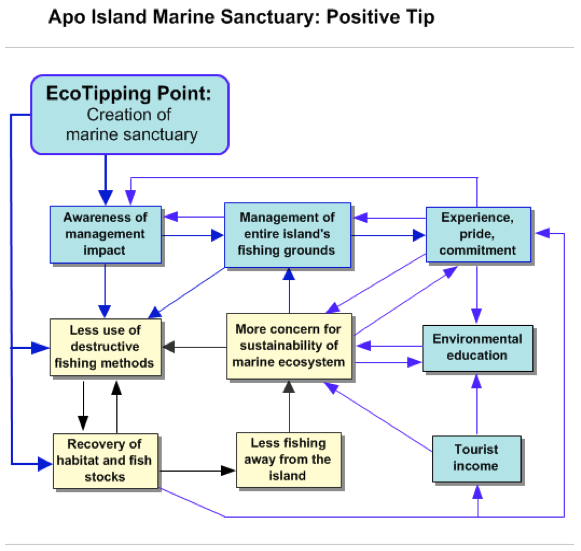

The central role of catalytic actions and mutually reinforcing feedback loops. EcoTipping Points cascade through and between social system and ecosystem. A small change to either system leads to larger changes in both. A positive tip generates improvements in social and ecological systems that reinforce one another to turn both systems from deterioration to health. The catalytic action – the EcoTipping Point – for Apo Island was establishment of the marine sanctuary, which set in motion numerous ecological and social changes. Most important was the fact that success with the sanctuary inspired local fishermen to devise and enforce regulations for their entire fishing grounds. Every round of success after that inspired the fishermen to improve the management regime even further. More fish stimulated tourism, which in turn reinforced the need for a vibrant marine ecosystem to continue attracting tourists. The economic benefits from tourism, the positive experience of exerting control over their destiny, and recognition as a model community for fisheries management stimulated numerous changes in the island society, setting in motion additional feedback loops (“virtuous cycles”) involving island infrastructure, education, and family planning.

Vicious cycles – the feedback loops driving decline - are central to the Apo Island story (see Feedback Analysis of the Apo Island Story). Positive change was set in motion when vicious cycles were reversed, transforming them into virtuous cycles that drove restoration with as much force as the vicious cycles drove decline. Reversing vicious cycles can be a tall order because they can be so powerful, but anything less is merely “swimming against the current.”

What does it take to reverse vicious cycles and transform them into virtuous cycles? What does it take to create “spinoffs” that form additional virtuous cycles to reinforce and consolidate restoration? The Apo Island story shows us key ingredients for success.

Ingredients for Success

- Shared community awareness and commitment. Strong democratic institutions and genuine community participation are prominent in EcoTipping Point stories. Of particular importance is a shared understanding of the problem and what to do about it, and shared ownership of the action that follows. Communities move forward with their own decisions, manpower, and financial resources. At Apo Island, creation of the sanctuary, and subsequent community management of Apo Island's fishing grounds, came out of community discussion. The local barangay government took the lead, and Apo Island was able to draw upon its traditional procedure for community decision making by assembling representatives of all Island families at the primary school playground (along with an ample supply of roast pork and other amenities) to discuss the issue at hand until reaching agreement, even if it took days of intensive discussion to do so.

- Outside stimulation and facilitation. Outsiders can be a source of fresh ideas. While action at the local level is essential, a success story typically begins when people or information from outside a community stimulate a shared awareness about a problem and introduce game-changing ideas for dealing with it. The marine sanctuary was created after three years of dialogue between Apo Islanders and Silliman University staff – a dialogue that helped the fishermen and their families to take stock of what was happening to the fishery and what might be done about it. Marine biologist Angel Alcala took some of the fishermen to a small no-fishing reserve at another island, where they could see the dramatic impact of fish protection on fish stocks. Later, NGO assistance was critical for securing the Island's local (barangay) government legal authority to exercise control over the Island's fishery. Years later, another NGO helped the Islanders to set up a community family planning program.

- Enduring commitment of local leadership. Trusted and persistent leaders inspire the deep-rooted and continuing community commitment and participation necessary for success. From the very beginning, a dynasty of barangay leaders was highly committed to the marine sanctuary. Their commitment was entwined with entrepreneurial involvement in the Island's tourist development and with their stewardship of educational initiatives for the entire community, made possible by tourist revenues. Although not all Islanders were convinced at the beginning that the sanctuary was a good idea, those who were committed persisted until the benefits became obvious to everyone, and long-term community commitment and action followed.

- Co-adaption between social system and ecosystem. Social system and ecosystem fit together, functioning as a sustainable whole. When Apo Islanders established their marine sanctuary, they set in motion a "social commons" to fit their "environmental commons" – their coral reef ecosystem and fishery. The social commons began with community management of the sanctuary and evolved to managing the fishing grounds around the Island. Social cooperation was facilitated by the network of trust and obligation in Apo's tight-knit community, where everyone is related by blood or marriage to almost everybody else. The cooperation worked because they drew on community wisdom to devise effective rules for protecting their fishery, and the rules were practical to enforce (see "Overcoming social obstacles" below). The marine ecosystem responded by repairing itself and better meeting community needs. Once the EcoTipping Point – the marine sanctuary and the social organization to implement it – set positive change in motion, normal social, economic, governmental, and ecological processes took it from there.

- "Letting nature do the work". EcoTipping Points give nature the opportunity to marshal its self-organizing powers to set restoration in motion. As soon as fish were protected in Apo's marine sanctuary, their high reproductive capacity enabled them to quickly repopulate the sanctuary. When destructive fishing was no longer allowed around the Island's fishing grounds, nature set in motion a complex restoration process for the entire coral ecosystem – something that human micro-management of the ecosystem could never achieve.

- Rapid results. Quick "payback" helps to mobilize community commitment. Three years after establishing the sanctuary, the increase in fish stocks was so dramatic that it inspired Apo Islanders to embark on managing their fishing grounds outside the sanctuary. Full recovery of fish catches outside the sanctuary took longer, but there were visible improvements from the beginning. The spectacular recovery of the Island's coral-reef ecosystem attracted tourism, reinforcing the commitment of Islanders to a healthy marine ecosystem. A substantial portion of the income from tourism went back to the community in the form of infrastructure (e.g., water supply, electrification, renovation of the Island's primary school) and community development projects (e.g., a local bakery, micro-financing, and marketing cooperatives), further reinforcing commitment.

- A powerful symbol. It is common for prominent features of EcoTipping Point stories to serve as inspirations for success, representing the restoration process in a way that consolidates community commitment and mobilizes community action. The marine sanctuary is a sacred site for Apo Island inhabitants. It is the centerpiece of a shared story of pride and achievement. They say that the sanctuary saved the island's marine ecosystem, the fishery, and their way of life. It is unthinkable to violate the sanctuary or what it represents.

- Overcoming social obstacles. The larger socio-economic system can present numerous obstacles to success on a local scale. For example, people may have so many demands on their time, it is difficult to find the time for community enterprises. The Island community devised ways to manage its marine ecosystem without making excessive demands on people's time. The sanctuary's no-fishing rule was easily enforced by a single person watching from the beach, a task rotated among Island families. Similarly, fishermen at work on the Island's fishing grounds could easily see if other fishermen didn't belong there or were using illegal fishing methods. Another common obstacle is government authority that stands in the way of a local community doing what is necessary. This is an issue of local autonomy. Apo Island's local government encountered this issue when it decided to exclude other fishermen from the Island's fishing grounds (with no precedent in Philippine law or tradition) and enforce a ban on destructive fishing methods (when the enforcement of existing fisheries laws was the domain of higher levels of government). Fortunately, the Islanders were able to negotiate approval from higher levels of government to embark on these innovations. Finally, the establishment of a national network of marine sanctuaries, called the National Integrated Protected Area System (NIPAS), which was inspired by Apo Island's success, posed a serious challenge to local autonomy. Before, management decisions for their fishery resided solely with Apo Islanders themselves, but now the NIPAS management board has final authority. One practical consequence has been that tourist fees, which went directly to the Island's local government before, now go to the national organization and return to the local government after considerable delay and reduction of the funds. The Islanders are still in the process of dealing with these challenges of national integration.

- Social and ecological diversity. Diversity provides more choices, and therefore more opportunities for good choices. Ecologically, the species richness (i.e., diversity) of Apo Island's marine ecosystem has enhanced its capacity for self-restoration. Socially, the Islanders created their sanctuary, and undertook the many innovations that followed, only after expanding (i.e., diversifying) their social horizons beyond the village to include dialogue with scientists from Silliman University. This helped to diversify their awareness of choices for action. Then, the rich diversity of the Island's coral reef enhanced its attractiveness for tourism, and tourism provided a more diversified base for the Island's economy. Before, the main sources of income were fishing, part-time farming, mat-weaving, and boat service for people and supplies to and from the island. Tourism brought other sources of income, such as working at the Island's two small hotels, providing services to the hotels (e.g., catering), selling T-shirts and sarongs to tourists, "home-stay" accommodation to backpackers, and expanding boat services to and from the island. Education has allowed some of the younger generation to pursue professional careers outside the Island, diversifying income sources even further and providing additional income for the local economy.

- Social and ecological memory. Learning from the past adds to the diversity of choices, including choices that proved sustainable by withstanding the "test of time." Social memory had a key role after Apo Islanders banned destructive fishing. The fishermen returned to traditional fishing practices such as hook-and-line, fish traps, and large-mesh gillnets, which they knew to be functional and more sustainable than destructive fishing practices. The ecological memory of the coral ecosystem was found in nature's design for sustainability through the intricate co-adaptations among the ecosystem's natural inhabitants, and this "memory" for sustainable design, built into the ecosystem, was the key to its recovery as a valuable resource for the Island. Social and ecological memory played a key role in deciding where to locate the sanctuary. The Islanders selected a highly degraded part of the Island's fishing grounds, which they considered to have the greatest potential for recovery, because they recalled it had the Island's richest coral ecosystem in the past. Finally, when the Islanders decided how many fish they should harvest as fish stocks recovered, they were able to fall back on their traditional value of "taking only what they need from the sea." With larger fish stocks, they could have increased their catch (and income) by continuing to fish "dawn to dusk" (as depleted fish stocks had forced them to do before). But instead, as fish stocks increased, they reduced the intensity of their fishing, keeping their total fish catch about the same as before – a wisely sustainable strategy. While devoting some of their "newfound" time to diversifying economic activities, the fishermen devoted much of it to family and community, which traditional values told them are most important for quality of life.

- Building resilience. "Resilience" is the ability to continue functioning in the face of sometimes severe external disturbances. The key is adaptability. Apo Islanders showed their adaptive capacity when tourism became so heavy that diving and snorkeling were damaging the coral and interfering with their fishing. Their experience managing their fishery gave them the insights and confidence necessary to impose restrictions on snorkeling and diving, even if it conflicted with short-term income from tourism. In the long term, spinoffs from the sanctuary, such as tourist income, local women's associations, general strengthening of community solidarity, quality education, and professional careers for some family members on the adjacent mainland have reinforced the ability of the island community to sustain its success in the face of unknown future challenges.

Feedback Analysis – The Apo Island Story

- Author: Gerry Marten

Negative Tip

The negative tipping point occurred throughout the Philippines with the introduction of destructive fishing methods such as dynamite, cyanide, and small-mesh fishing nets. Two interlocking and mutually reinforcing vicious cycles were set in motion:

- The use of destructive fishing methods reduced fish stocks directly through overfishing. Destructive fishing reduced the stocks indirectly by damaging their coral habitat. With declining fish stocks, the fishermen were more and more compelled to use destructive fishing methods to catch enough fish, further degrading habitat and reducing fish stocks.

- As home fishing grounds deteriorated, fishermen traveled further and further to find less damaged sites where they could catch some fish. They used destructive fishing without restraint because places far from home were of no particular significance for future fishing. Sustainability of the island’s fishing grounds also became less important as fishing shifted away from the island.

The downward spiral of destructive fishing, habitat degradation, diminishing fish stocks, and fishing further from home continued until many places were virtually worthless for fishing.

Positive Tip

The positive tipping point for Apo Island was creation of a marine sanctuary, setting in motion a cascade of changes that reversed the vicious cycles in the negative tip. In the diagram below the vicious cycles transformed to virtuous cycles are shown in black. Additional virtuous cycles that arose in association with the marine sanctuary are shown in green and red.

- The sanctuary served as a nursery, contributing directly to the recovery of fish stocks in the island’s fishing grounds.

- Success with the sanctuary stimulated the fishermen to set up sustainable management for the fishing grounds. A virtuous cycle of increasing fish stocks, accompanied by growing management experience, pride, and commitment to the sanctuary, was set in motion.

- As fishing improved around the island, fishermen were no longer compelled to travel far away for their work. Fishing right at home, where they had to live with the consequences of their fishing practices, reinforced their motivation for sustainable fishing.

Yellow: Vicious cycles reversed by the positive tip to form virtuous cycles.

Blue: Spin-offs and associated virtuous cycles.

“Lock in” to sustainability came with the formation of additional virtuous cycles:

- The increase in fish populations and the health of the reef ecosystem around the island led to tourism. Earnings from tourism provided a strong impetus to keep the marine ecosystem healthy. Although coral reef tourism is frequently not sustainable because tourists damage the coral, the experience of Apo Island’s inhabitants with managing their marine sanctuary and fishing grounds gave them the ability to manage tourism so it didn’t damage the coral.

- Positive results from the marine sanctuary stimulated the island community to develop a strong marine ecology program in their elementary school, so the new generation values the island’s marine ecosystem and knows how to keep it healthy.

- Income from tourism gave islanders the ability to send their children to high school and university on the mainland. A few have gone on to study marine science in graduate school. The high educational level of the island’s new generation will give it the ability to deal with unexpected future threats to their fishery and marine ecosystem.

- Enhanced ecological awareness has led to a family planning program aimed at preventing an increase in population that would overburden the island’s fishery in the future.

In summary, the Apo Island story shows how EcoTipping Points provide a paradigm of hope in a world of accelerating environmental deterioration by offering an alternative to micro-management. The information, material, and energy inputs to micromanage solutions for the myriad environmental problems that we face are simply beyond human capacity. EcoTipping Points are not magic bullets to solve environmental problems overnight. But in a world of limited resources and powerful social and ecological currents, they are efficient ways to help the self-organizing powers of nature and human nature to move environmental support systems toward greater health.

Acknowledgments

Angel Alcala, Alan White, Laurie Raymundo, Aileen Maypa, and Mario Pascobello provided information for the Apo Island story. Portia Nillos helped in numerous ways during my visit to Apo Island.

References

- Alcala, A. C. 2001. Marine reserves in the Philippines: historical development, effects and influence on marine conservation policy. Bookmark, Makati City, Philippines.

- Cadiz, P. L., and H. P. Calumpong. 2000. Analysis of revenues from ecotourism in Apo Island, Negros Oriental, Philippines. Proceedings of 9th International Coral Reef Symposium (Bali, Indonesia, 23-27 October 2000), Volume 2:771-774.

- Liberty’s Community Based Lodge and Paul’s Community Diving School, Apo Island.

- Maypa, A.P., G. R. Russ, A. C. Alcala, and H. P. Calumpong. 2002. Long-term trends in yield and catch rates of the coral reef fishery at Apo Island, central Philippines. Marine Freshwater Research 53:207-213.

- Raymundo, L. J., and A. P. Maypa. 2003. Chapter 14. Apo Island marine sanctuary, Dauin, Negros Oriental. Pages 61-65 in Philippine coral reefs through time. The Marine Science Institute, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Philippines.

- Raymundo, L. J., and A. T. White. 2005. 50 years of scientific contributions of the Apo Island experience: a review. Silliman Journal (50th Anniversary Issue), Silliman University, Dumaguete, Philippines.

- Reboton, C., and H. P. Calumpong. 2003. Coral damage caused by divers/snorkelers in Apo Island marine sanctuary, Dauin, Negros Oriental, Philippines. Philippine Scientist 40:177-190.

- Russ, G. R., and A. C. Alcala. 1996. Do marine reserves export adult fish biomass? Evidence from Apo Island, central Philippines. Marine Ecology Progress Series 132:1-9.

- Russ, G. R., A. C. Alcala. 1998. Natural fishing experiments in marine reserves 1983-1993: community and tropic responses. Coral Reefs 17:383-397.

- Russ, G. R., and A. C. Alcala. 1999. Management histories of Sumilon and Apo marine reserves, Philippines, and their influence on national marine resource policy. Coral Reefs 18:307-319.

- Russ, G. R., and A. C. Alcala. 2004. Marine reserves: long-term protection is required for full recovery of predatory fish populations. Oecologia 138:622-627.

- Russ, G. R., A. C. Alcala, A.P. Maypa, H. P. Calumpong, and A. T. White. 2004. Marine reserve benefits local fisheries. Ecological Applications 14:597-606.

Replication of Apo Island’s Example to Other Villages in the Philippines

- Author: Portia Nillos-Kleiven

- Angelo King Center for Research and Environmental Management, Silliman University

- Editorial contributions: Gerry Marten and Regina Gregory

EcoTipping Points follow-up reports are directed at EcoTipping Point cases that (a) have been exceptionally successful and (b) have a substantial number of replications. The purpose of the questions below is to determine what can be learned from detailed study of the replication experience.

Read other follow-up reports:

- Replications of Punukula Example to Other Villages in Andhra Pradesh, India

- Summary of Reconnaissance for an In-Depth Study of Agroforestry and Community Forests in Nakhon Sawan, Thailand

- Report on field visits to Yadfon Association’s working areas in Trang Province, Thailand

Portia Nillos compiled a summary of what has happened with spreading the initial success at Apo Island to other villages. The report below represents the first step in a larger study by the EcoTipping Points Project to identify what it takes to successfully leverage a turnabout from environmental and social decline to restoration and sustainability.

Quetions 1.

- Approximately how many replications have been attempted?

- Have they all been done by the same organization?

- If not, what organizations have done it, and approximately how many replications have been attempted by each organization?

- Who is a useful contact person in each organization?

In the whole Visayas as of late 2008, there are 564 marine protected areas (MPAs), with 559 of them considered as community-based, including the Apo Island MPA, even though Apo is considered as part of the National Integrated Protected Areas System (NIPAS). As the Sumilon and Apo Island MPAs are the oldest among these, then it is currently 557 MPAs that were established after the Apo Island MPA was established.

These MPAs were set up by many local government units and different organizations in different provinces in the Visayas. The following is a short list of some of the organizations that have been catalytic in the establishment of MPAs in each province:

- Negros Oriental – Silliman University-Angelo King Center for Research and Environmnetal Management (SUAKCREM), Environment and Natural Resources Division of the Province of Negros Oriental, Local Government Units (LGUs)

- Negros Occidental – Philippine Reef and Rainforest Conservation Foundation Inc. (PRRCFI), City Government of Sagay

- Cebu – Coastal Conservation and Education Foundation (CCEF) in the Cebu mainland, Law of Nature Foundation (in the Bantayan Island Group), EcoGov (US Agency for International Development (USAID) funded project implemented through CCEF and other non-government organizations (NGOs))

- Bohol – Bohol Integrated Development Foundation (BIDEF), Bohol Alliance of Non-Government Organizations Network (BANGON), Participatory, Research, Organization of Communities and Education towards Struggle for Self-Reliance-Bohol (PROCESS Bohol), Bohol Environment Management Office (BEMO, province level)

- Leyte – Guiuan Development Foundation, Inc.

- Antique – Hayuma Foundation, Provincial Government of Antique

International funding agencies, such as USAID, and the German Development Service have also funded and provided technical assistance in establishing many MPAs in the Visayas, usually in collaboration with municipal and city mayors and local organizations. It should be noted also that a majority of the MPAs set up in the provinces were established collaboratively, usually by the LGU, NGOs, and local people’s organizations.

Question 2.

- What was actually done to make replications happen? (This may not be the same for all replicates.)

A majority, if not all, of the replications were done with the assistance of the local government units (municipal or city level). In 1992, the Philippine government passed the Local Government Unit Code (Republic Act 7160, or the Local Government Code), which contained a clause that required all municipalities and cities to set aside 20% of their municipal waters as marine reserves/sanctuaries.

For many MPAs, especially in Negros Oriental, the Apo Island model was adopted. This is the tri-partite model where the NGO is the primary catalyst, the community was the main manager, and the LGU provided long-term financial support through institutionalization of the program. The NGO or external organization usually provided the initial impetus for the program, with the deployment of community organizers and technical resource persons for the first 2 years, with the aim of training the community to eventually take over the management of the sanctuary/MPA. During the first 2 or 3 years, the LGU is on board to participate in all the decision making processes, so that the institutionalization of the program can also take place. At the end of the 2nd or 3rd year, the MPA is usually “legalized”, with funding provided by the LGU to support the maintenance of the sanctuary. In southern Negros, the LGU usually implemented user’s fees for divers in the sanctuary as a sustainable long-term source of funds for the MPA/CRM (coastal resource management) program.

The MPAs that are usually successful in the long-term are those that have a viable source of funds. It is therefore no surprise that the municipality of Dauin, which has 10 sanctuaries (including Apo Island) and is considered the diving capital of Negros Oriental, has successfully managed its sanctuaries as they have sufficient funding coming in from user’s fees. (The latest, unofficial figure was P12 million for 2008 from diving fees alone.)

Queston 3.

- Have all the replications been equally successful? Have they been as successful as the original site?

The “functionality” of 564 marine reserves in the Visayas was evaluated by a group of researchers from SUAKCREM in 2008. “Functionality” as used in this context was based on a rating criteria that gave 60% weight to management aspects (#1-3 below), and 40% weight to the biophysical aspects (#4 and #5). A MPA is considered functional if it rates at least 6 out of the 10 possible points that can be attained using this rating system.

- Good protection status in terms of existence of guards and a regular patrolling regime, buoys and signs, and patrol boat;

- Sustained funding support by local government units;

- Management by a local government unit or by a local government unit in partnership with people’s organizations, NGOs, or some other community-based associations;

- At least a “Medium” fish biomass (at least ca. 20 tons/km2) and high fish density and biodiversity;

- At least a “Fair” live hard coral/seagrass/mangrove cover (ca. 25% and above).

Table 1 provides a summary of their findings.

Table 1. A summary of functional marine reserves per major island group in the Visayas.

| Island | Functional | Non-Functional | Paper Reserves | Newly Established | Total | % Functional |

| Bohol | 62 | 92 | 3 | 12 | 169 | 36.69 |

| Cebu | 60 | 40 | 0 | 20 | 120 | 50.00 |

| Leyte | 10 | 42 | 6 | 19 | 77 | 12.99 |

| Negros | 26 | 14 | 1 | 10 | 51 | 50.98 |

| Panay | 19 | 27 | 22 | 4 | 72 | 26.39 |

| Samar | 6 | 23 | 11 | 20 | 60 | 10.00 |

| Siquijor | 7 | 5 | 0 | 3 | 15 | 46.67 |

| Total | 190 | 243 | 43 | 88 | 564 |

Among these provinces, initial analysis of the functionality of existing MPAs indicate that the highest percentage of functional ones are in Region VII, which includes the provinces of Negros Oriental, Cebu, and Bohol. These are also the MPAs that closely resemble the Apo Island model (tri-partite management, with strong community participation, funding support from the local government, and with constant technical support from NGOs throughout the years).

If not, what has been the range of outcomes? (This is the most important question. I want to get an idea of what happened not only with some of the most successful and unsuccessful replications – and where they are located, so we can visit them for documentation – but also replications that were in-between and perhaps more typical in their success.)

As one can note, not all reserves have been as successful as Apo Island. The most successful ones are mostly in Bohol, Cebu, and Negros Oriental provinces (see list of the 190 functional MPAs in the Visayas, Table 2). It should be noted that although Negros Oriental does not have as many MPAs as the two other provinces, it has the highest percentage of functional MPAs in the whole Visayas (refer to Table 1).

The majority have attained moderate success, while others have been total failures (those considered as “paper reserves”). The latter are those that have been declared only on paper by the LGUs to comply with the Local Government Unit Code, but no groundwork was done in these MPAs and they are technically not considered as MPAs although they are legally established.

Table 2. List of functional marine reserves in the Visayan provinces.

| Province | Municipality/City |

| Aklan | |

| Bel-is Fish Sanctuary and Fish Reserve | Buruanga |

| Tangalan Fish Sanctuary and Fishery Reserve | Tangalan |

| Antique | |

| Abiera Fish Sanctuary | Sebaste |

| Barusbus Marine Sanctuary | Libertad |

| Batabat Coral Reef Reserve | Barbaza |

| Bulanao Marine Sanctuary | Libertad |

| Igdalaguit Municipal Fish Sanctuary | Tobias Fornier |

| Lamawan Pony Marine Protected Area | San Jose de Buenavista |

| Lipata Fish Sanctuary | Culasi |

| Nogas Island Marine Reserve | Anini-y |

| Pucio Marine Sanctuary | Libertad |

| Puntod Sebaste Shoal (Marine Protected Area) | Sebaste |

| San Roque Marine Sanctuary | Libertad |

| Seco Island Marine Reserve | Tibiao |

| Taboc Marine Sanctuary | Libertad |

| Tingib Marine Sanctuary | Pandan |

| Union Marine Sanctuary | Libertad |

| Bohol | |

| Aguining Fish Sanctuary | Carlos P. Garcia |

| Alejawan Marine Sanctuary | Duero |

| Asinan Reef Fish Sanctuary | Buenavista |

| Balicasag Island Marine Reserve | Panglao |

| Basdacu Fish Refuge and Sanctuary | Loon |

| Basdio Marine Sanctuary | Guindulman |

| Batasan Island Marine Sanctuary | Tubigon |

| Bilang-bilangan Fish Sanctuary | Tubigon |

| Bil-isan Fish Sanctuary | Panglao |

| Bingag Marine Sanctuary | Dauis |

| Bonkokan Ubos Marine Sanctuary | Lila |

| Cabacongan Fish Sanctuary | Loon |

| Cabantian Marine Sanctuary | Guindulman |

| Cantagay Marine Sanctuary | Jagna |

| Canuba Marine Sanctuary | Jagna |

| Cataban Fish Sanctuary | Talibon |

| Catarman Marine Sanctuary | Dauis |

| Catugasan Marine Sanctuary | Lila |

| Cuaming Fish Sanctuary | Inabanga |

| Cuasi Fish Refuge and Sanctuary | Loon |

| Dao-San Isidro Marine Sanctuary | Dauis |

| Doljo Fish Sanctuary | Panglao |

| Eastern Cabul-an Marine Sanctuary | Buenavista |

| Guinacot Marine Sanctuary | Guindulman |

| Guindacpan Marine Sanctuary | Talibon |

| Guiwanon-Punta Cruz Marine Sanctuary | Maribojoc |

| Hambongan Marine Sanctuary | Inabanga |

| Handumon Marine Sanctuary | Getafe |

| Hinongatan West Marine Sanctuary | Bien Unido |

| Ipil Marine Sanctuary | Jagna |

| Itum Marine Sanctuary | Duero |

| Jandayan Sur Marine Sanctuary | Getafe |

| Langkis Marine Sanctuary | Duero |

| Lapinig Island Fish Sanctuary | Carlos P. Garcia |

| Larapan Marine Sanctuary | Jagna |

| Lawis Fish Sanctuary | Calape |

| Madangog Fish Sanctuary | Calape |

| Madua Norte Marine Sanctuary | Duero |

| Madua Sur Marine Sanctuary | Duero |

| Magtongtong Fish Sanctuary | Calape |

| Malinao Marine Sanctuary | Lila |

| Maraag Marine Sanctuary | Maribojoc |

| Mawi Marine Sanctuary | Duero |

| Naatang Marine Sanctuary | Jagna |

| Nagsulay Marine Sanctuary | Lila |

| Nausok Marine Sanctuary | Jagna |

| Pamilacan Island Fish Sanctuary | Baclayon |

| Pangdan Marine Sanctuary | Jagna |

| Pantudlan Fish Sanctuary | Loon |

| Pasil (Kawasihan) Reef Marine Sanctuary | Candijay |

| Pig-ot Marine Sanctuary | Loon |

| Poong-Garcia Marine Sanctuary | Carlos P. Garcia |

| Sinandigan Marine Sanctuary | Ubay |

| Sondol Fish Sanctuary | Loon |

| Song-On Fish Refuge and Sanctuary | Loon |

| Sta Filomena (Sta. Fe) Marine Sanctuary | Alburquerque |

| Tabalong Marine Sanctuary | Dauis |

| Tangnan Marine Sanctuary | Loon |

| Taongon-Canandam Marine Sanctuary | Dimiao |

| Taug-Tiguis Marine Sanctuary | Lila |

| Tawala Marine Sanctuary | Panglao |

| Ubayon Marine Sanctuary | Loon |

| Capiz | |

| Olotayan Island Marine Sanctuary | Roxas City |

| Cebu | |

| Arbor Marine Sanctuary | Boljoon |

| Atop-atop Marine Sanctuary | Bantayan |

| Bagacay Fish Sanctuary | Sibonga |

| Balud-Consolacion Marine Park and Sanctuary | Dalaguete |

| Barili Marine Sanctuary | Barili |

| Basdiot Fish Sanctuary | Moalboal |

| Bato Seagrass and Marine Sanctuary | San Remegio |

| Batong Diyut Marine Sanctuary | Carmen |

| Binlod Marine Sanctuary | Argao |

| Bogo Marine Sanctuary | Argao |

| Bulasa Marine Sanctuary | Argao |

| Busogon Fish Sanctuary | San Remegio |

| Campalabo Marine Reserve/Sanctuary | Pinamungahan |

| Capitancillo Marine Sanctuary | Bogo |

| Casay Marine Park and Sanctuary | Dalaguete |

| Casay Marine Sanctuary | Argao |

| Colase Marine Sanctuary | Samboan |

| Daan-Lungsod and Guiwang Marine Sanctuary | Alcoy |

| Doong Marine Sanctuary | Bantayan |

| Gawi Marine Sanctuary | Oslob |

| Gilutongan Island Marine Sanctuary | Cordova |

| Guiwanon Marine Sanctuary | Argao |

| Hilantagaan Daku Fish Sanctuary | Sta. Fe |

| Hinablan Marine Sanctuary | Badian |

| Kinawahan Fish Sanctuary | San Remegio |

| Lambug Seagrass and Fish Sanctuary | Badian |

| Langtad Marine Sanctuary | Argao |

| Legaspi Marine Sanctuary | Alegria |

| Libas Marine Sanctuary | Borbon |

| Libertad Marine Sanctuary | Poro |

| Liloan Marine Sanctuary | Liloan |

| Luyang Fish Sanctuary | San Remegio |

| Madridejos Marine Sanctuary | Alegria |

| Matutinao Marine Sanctuary | Badian |

| Nalusuan Marine Sanctuary | Cordova |

| North Granada Marine Sanctuary | Boljoon |

| Ocoy Marine Reserve (Jojo de la Victoria Memorial Reef) |

Sta. Fe |

| Pandong Bato Marine Sanctuary | Carmen |

| Pasil Marine Sanctuary | Santander |

| Pescador Island Marine Park with Sanctuary | Moalboal |

| Poblacion Marine Sanctuary Poblacion Marine Sanctuary |

Argao Alcoy |

| Pooc Marine Sanctuary | Sta. Fe |

| Saavedra Fish Sanctuary | Moalboal |

| Santiago Marine Sanctuary | San Francisco |

| Sillion Marine Sanctuary | Bantayan |

| Siocon Marine Sanctuary | Bogo |

| Calumbuyan (Sogod) Fish Sanctuary | Sogod |

| Sta. Filomena Marine Sanctuary | Alegria |

| Sto. Niño-Looc Marine Sanctuary | Malabuyoc |

| Sulangan (Panitugan) Marine Sanctuary | Bantayan |

| Sumilon Island Fish Sanctuary | Oslob |

| Tabunan Marine Sanctuary | Borbon |

| Talaga Marine Sanctuary | Argao |

| Talo-ot Marine Sanctuary | Argao |

| Tambongon Fish Sanctuary | San Remegio |

| Tamiao Marine Sanctuary | Bantayan |

| Tulic Marine Sanctuary | Argao |

| Victoria Fish and Seagrass Sanctuary | San Remegio |

| Zaragosa Fish Sanctuary | Bantayan |

| Eastern Samar | |

| Bagongbanwa Marine Reserve and Sanctuary | Guiuan |

| Mandalukon Marine Reserve | Giporlos |

| Mantampok Islet Fish Sanctuary | Quinapondan |

| Monbon Fish Sanctuary | Lawaan |

| Panaloytoyon Fish and Marine Sanctuary | Quinapondan |

| Puno Point Marine Reserve | Guiuan |

| Guimaras | |

| Lawi Marine Reserve | Jordan |

| Leyte | |

| Apale and Tolingon Fish Sanctuary | Isabel |

| Dumana Marine Sanctuary | Inopacan |

| Hilapnitan Marine Sanctuary | Baybay |

| Tres Islas Marine Sanctuary | Inopacan |

| Tumakin Gamay/ Dako Marine Sanctuary | Inopacan |

| Negros Occidental | |

| Danjugan Island Marine Reserve and Sanctuaries | Cauayan |

| Sagay Protected Seascape | Sagay |

| Sipalay City Marine Reserve | Sipalay |

| Negros Oriental | |

| Agan-an Marine Reserve | Sibulan |

| Andulay Marine Reserve | Siaton |

| Apo Island Protected Landscape and Seascape | Dauin |

| Balaas Marine Reserve | Manjuyod |

| Banilad Marine Reserve | Dumaguete |

| Bio-os Marine Reserve | Amlan |

| Bolisong Marine Sanctuary | Manjuyod |

| Bongalonan Marine Sanctuary | Basay |

| Cabugan Marine Reserve | Bindoy |

| Cabulotan Marine Reserve | Tayasan |

| Calag-calag Fish Sanctuary | Manjuyod |

| Campuyo Marine Sanctuary | Manjuyod |

| Iniban Marine Reserve | Ayungon |

| Luca Lipayo Marine Reserve | Dauin |

| Lutoban Marine Reserve | Zamboanguita |

| Maayong Tubig Marine Reserve | Dauin |

| Malusay Marine Reserve | Guihulngan |

| Masaplod Norte Marine Reserve | Dauin |

| Masaplod Sur Marine Reserve | Dauin |

| Poblacion District 1 Marine Reserve | Dauin |

| San Jose Marine Reserve | San Jose |

| Tandayag Marine Reserve | Amlan |

| Tinaogan Marine Reserve | Bindoy |

| Siquijor | |

| Candaping B Marine Sanctuary | Maria |

| Caticugan Marine Sanctuary | Siquijor |

| Lalag-Bato Marine Reserve | Lazi |

| Sandugan Marine Sanctuary | Larena |

| Talayong Marine Sanctuary | Lazi |

| Tubod Marine Sanctuary | San Juan |

| Tulapos Marine Sanctuary | Enrique Villanueva |

| Southern Leyte | |

| Cogon Fish Sanctuary | Anahawan |

| Lipanto Marine Sanctuary | St. Bernard |

| Napantao Marine Sanctuary | San Francisco |

| Sabang Fish Sanctuary | Hinundayan |

| San Antonio/ Tomas Oppus Marine Reserve | Tomas Oppus |

Questions 4.

- If the replications were not equally successful (or some were not as successful as the original site), why was the replication more successful or less successful at different places (in the opinion of people involved in the replication)?

There are several factors that influence the long-term success of an MPA:

- Community readiness, which can be achieved only by a proper community organizing process that can take anywhere from 6 months to 2 years. This is where crucial external support comes in, as the best community organizers are usually those that are not from the community itself and have some degree of professional training/experience.

- Enlightened political leaders – there has been no MPA/CRM program that has progressed without the support of the mayor or at least the barangay [village] captain. In most cases, the support has to come from the municipal level, but there are certain cases where strong support from the barangay captains have proved sufficient even without the support of the mayor or the municipality.

- Sustainable financing mechanisms – this usually takes the form of user’s/ diver’s fees, or some form of financial support from the municipal/city government such as honorarium for the guards, and funds to maintain the marker buoys and patrol boat. There have been many cases of MPAs that were successful in the beginning because there was external funding from a NGO, but when the funding dried up, so did the support from the local community and thus the decline in the management of the sanctuary/MPA. The ones that have been most successful, however, are those that provide income to the community (e.g., the popular diving areas in Negros, Cebu and Bohol).

- Although not applicable in most MPAs, long-term technical support for monitoring from an NGO or an external organization seems to be a contributing factor for long-term success. MPAs that have a strong affiliation with external organizations also usually get a lot of “advertising” and this can translate to additional funds for the MPA. Also, the presence and constant support from external organizations also seems to serve as an encouragement to the community to continue with the work of managing an MPA.

Question 5.

What is the opinion of people involved in the replication, with regard to:

- our story line for that case’s “negative tip” and “positive tip”;

- the structure that we diagrammed for the vicious cycles and virtuous cycles in that case;

- the nature and role of each “ingredient” in our list of ETP ingredients;

- other “ingredients” that the people involved consider significant for success.

In the bigger picture, the establishment of the MPA in Apo Island was indeed the positive tip that turned around the vicious cycle and started the trend of MPAs in the Visayas, if not the whole Philippines. However, the establishment of the MPA itself would not have happened if it was not for the following crucial events that came together at a particular time. If one of these elements was absent, the sanctuary probably would not have been set up.

- Dr. Angel Alcala, who believed that establishing a sanctuary will improve the local fisheries in a community. Although this idea is not new and has been in practice in the Philippines and many other Pacific islands before, people have forgotten about it, and he made it his task that people should know about it.

- The work of community organizers from the Silliman University Social Work Department was crucial in garnering the trust of the community and support for the sanctuary in the beginning. Dr. Alcala knew that changing the perception of the community would require social scientists, and not marine biologists or fisheries people, and he had the good sense to tap the support of community organizers from the university.

- The strong leadership of the Pascobello family at the beginning of the sanctuary project—the barangay captain at that time believed that the sanctuary would work and was thus able to harness manpower for guarding it because of their political clout.

- The initial success of the Apo Island sanctuary attracted external funding, both from the government and the private sector. In the mid 1990s, the sanctuary became part of the NIPAS system, and this assured the long-term financial and technical support from the government. In the early 1990s, the resorts and dive shop in the island were set up, and this ensured the steady flow of tourists and divers—which contribute a lot to the island’s economy. With Apo Island becoming known as a world class dive site, more resorts were put up in the Negros mainland, mostly in Dauin, and this in turn encouraged the municipality to set up sanctuaries in the mainland to cash in on the tourism boom. The steady flow of income from diving tourism is a big factor that ensured the long-term sustainable funding for the MPA not only in Apo but also in the Negros mainland. It was in everybody’s interest to maintain the MPAs because it was good for the local economy, and of course the divers kept on coming back because they are assured of world class dive sites in the Negros Oriental area.

The initial success of the MPA was maintained throughout the years because of the constant support of the community. The inter-generational support (grandparents, parents and children) for the MPA in Apo Island remains high despite the perceived downward trend in management after the Protected Area Management Board (PAMB) took over in 1994 (Oracion, 2006). It is expected that this support will continue as the younger community members who are growing up with MPA-oriented values realize the full range of economic benefits from the MPA, and take over the roles of managing the MPA from their parents.

Suggestions for Further Reading:

- Oracion, E. G. 2006. Are the children willing? Intergenerational support for marine protected area sustainability. Silliman Journal 47(1): 48-74.

- Oracion, E. G. 2007. Dive tourism, coastal resource management, and local government in Dauin. Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society 35:149-178.

- Quibilan, M. C., P.M. Aliño, S.G. Vergara, and R.B. Trono. 2008. Establishing MPA networks in marine biodiversity conservation corridors. Tropical Coasts 15(1): 38-45.