EcoTipping Points

- How do they work?

- Leveraging vicious

cycles to virtuous - Ingredients for success

- Create your own

EcoTipping Points!

Stories by Region

- USA-Canada

- Latin America

- Europe

- Middle East

- South Asia

- Southeast Asia

- East Asia

- Africa

- Oceania-Australia

Stories by Topic

- Agriculture

- Business

- Education

- Energy

- Fisheries

- Forests

- Public Health

- Urban Ecosystems

- Water and Watersheds

Short Videos

- Saving a Coral Reef and Fishery (Apo Island, Philippines)

- Community Gardens Reverse Urban Decay (NYC, USA)

- Community Forests Reverse Tropical Deforestation (Thailand)

- Escaping the Pesticide Trap (India)

- Rainwater Harvesting and Groundwater Replenishment (Rajasthan, India)

How Success Works:

- Saving a Coral Reef and Fishery (Apo Island, Philippines)

- Community Gardens Reverse Urban Decay (NYC, USA)

- Community Forests Reverse Tropical Deforestation (Thailand)

- Escaping the Pesticide Trap (India)

- Rainwater Harvesting and Groundwater Replenishment (Rajasthan, India)

Human Ecology:

Principles underlying

EcoTipping Points

USA - Green Business in America

- Author: Regina Gregory

- Posted: July 2012

American business has come a long way in becoming more eco-friendly, but still has a long way to go. This report presents some ideas on greening existing businesses, creating new green businesses, and making more fundamental changes to the economy.

American business and the environment have long been at odds. In fact, our economy has been called a “suicide economy” because what we take, make, and waste destroys the very foundation we depend on. American business is the principal culprit in environmental destruction and, according to Hawken (1993) and Anderson (2009), it is also the only entity powerful enough to solve the problem—i.e., to create a “restorative economy” instead.

History

In the U.S. a “sustainability revolution” or “new industrial revolution” is said to have started in the period around 1970. In response to various environmental problems, the federal government passed the National Environmental Policy Act (1969), the Clean Air Act (1970), the Clean Water Act (1972), the Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (1972), and the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (1976). Businesses quickly became “greener” in order to comply with the laws and avoid heavy fines. The Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act of 1980 provided further encouragement, as owners became directly liable for environmental damages (Sullivan 1992).

In time, U.S. companies began to see that apart from avoiding fines, becoming greener also led to cost savings. More efficient materials and energy use, less packaging, and selling waste (recycling), had a positive effect on the “bottom line” (Sullivan 1992). There is still ample room for improvement. According to Anderson (2009, p. 40),

Ninety-seven percent of all the energy and material that goes into manufacturing our society’s products is wasted. Mountains of tailings pile up at the mines. Energy goes up the smokestack, leaks out the wires, and ends up as waste heat. Year after year we send a tsunami of scrap to inundate our landfills. Only about 3 percent ends up as a finished product that still has any value six months later.

1970 also marked the first Earth Day, and environmental awareness among the general public began to grow. Environmental organizations sprang up for causes big and small. Green consumers emerged—people increasingly made their purchases with the environment in mind. Thus we have seen a proliferation of claims to be organic, natural, recycled, and certified by various entities—the Forest Stewardship Council for wood products; the Marine Stewardship Council for fisheries; the Green Building Council for energy efficiency; the Institute for Market Transformation to Sustainability for materials; B Lab for “benefit corporations.” Corporations found that having a green image was a marketing advantage. Some have engaged in insincere “greenwashing.”

A whole class of green investors emerged as well—“impact investors” who want to do well while doing good, and who care about the “triple bottom line” of profit, people, and the planet. Today, a large number of financial firms feature socially responsible investment portfolios. Some, such as Triple Bottom Line Investing (tbli.org) and Green Century Funds (greencentury.com), are devoted solely to this field. Dow Jones even devised Sustainability Indexes to help guide green portfolios. Newsweek magazine publishes an annual Green Company Rankings.

Thus sustainable business has “become a normal, even mundane, part of the business landscape” and

companies continue to make, meet, and even exceed ambitious environmental goals related to their use of materials and resources, the emissions of their operations (as well as their suppliers’), the efficiency of their offices and factories, the ingredients of their products, and what happens to those products at the end of their useful lives (Makower et al. 2012, p. 4).

A general shift in gross domestic product from manufacturing to services, information technology, and finance has also lightened the ecological footprint over the years.

Greening Existing Businesses

One seven-step process, popular with consultants, was presented by Perry Goldschein at the Sustainable Brands 2010 conference:

- Set measurable goals – Begin with simple steps close to home.

- Stakeholder engagement – Include stakeholders from the start of the consultation process.

- Sustainability issues mapping – Use interactive maps to prioritize key issues.

- Sustainability management systems – Develop a framework to ensure environmental concerns are considered in tandem with other considerations.

- Lifecycle assessment – Design products with a “cradle-to-cradle” approach.

- Sustainability reporting – Ensure that consumers and stakeholders have easy access to reports on sustainability efforts.

- Sustainability branding – Advertise as a green product (Lu 2010).

Other consultants have put more emphasis on the importance of employee and community engagement, and working with environmental non-government organizations.

Here we examine as case studies the “poster child” of a green business overhaul—Interface Carpet Company—along with two American icons selected at random, McDonald’s and Walmart.

Interface Carpet

Probably the best (or at least best-known) example of greening an existing business is Interface Carpet Company. Its founder and CEO Ray Anderson was so inspired by Paul Hawken’s book, The Ecology of Commerce, that he made a “mid-course correction” from being a corporate plunderer to being “America’s greenest CEO.” Anderson was already an innovator in carpet tiles, which allow parts of a carpet to be replaced instead of the entire thing, and carpet “leasing” in which only the use of the carpet is sold. In 1994 Anderson stunned his board of directors and workforce with a proclamation that the firm would embark on a climb up Mount Sustainability, with the summit being zero footprint—hence Mission Zero. He provided this diagram to illustrate:

Figure 1. Mount Sustainability (Anderson 2009, p. 6)

Based on the principle that sustainability requires that the linear take-make-waste process must be changed to a cyclical process, in which nothing is taken that cannot be renewed, Anderson stated,

We’re going to push the envelope until we no longer take anything the earth can’t easily renew. We’re going to keep pushing until all our products are made from recycled or renewable materials. And we’re not going to stop pushing until all our waste is biodegradable or recyclable, until nothing we make ends up as pollution. No gases up a smokestack, no dirty water out a pipe, no piles of carpet scraps to the dump (Anderson 2009, p. 17).

For a company with annual sales of more than a billion dollars of products that are mostly a complex mix of petrochemicals, this was a tall order indeed.

Anderson’s drawing of Mount Sustainability is very simple, but the “mountain” has seven faces, he says, each of which must be climbed:

- moving toward zero waste;

- increasingly benign emissions, working up the supply chain;

- increasing efficiency and using more and more renewable energy;

- closed-loop recycling, copying nature’s way of turning waste into food;

- resource-efficient transportation, from commuting to logistics to plant siting;

- sensitivity hook-up, changing minds and getting employees, suppliers, customers, and our own communities on the same page; creating a corporate “ecosystem,” to borrow a term from nature, with cooperation replacing confrontation;

- redesigning commerce, teaching a new Economics 101 that puts it all together and assesses accurate costs, sets real prices, and maximizes resource-efficiency (Anderson 2009, p. 41-42).

Wastes

Assuming that the employees themselves know best about how manufacturing processes could be improved, the Quality Utilizing Employee Suggestions and Teamwork (QUEST) program was started in 1995. Every manager was given a goal of 10% annual waste reduction, and their bonuses were tied to how successful they were. All the other employees are financially rewarded for their waste reduction ideas as well. For instance, one came up with the idea of portable creels for feeding yarn, which reduced scrap yarn by 54%. Another thought of changing the way yarn is moved around the factory to minimize damage.

Water use was reduced by 75%, and Interface was able to shut down 71% of its wastewater pipes as well as one third of its smokestacks due to process changes. Carpet waste previously sent to the landfill has been reduced by 78%. Overall Interface has achieved a 41% reduction in waste cost per unit, resulting in $438 million in avoided costs since 1994.

Energy

Interface installed energy management systems, upgraded equipment, and skylights and solar tubes to improve energy efficiency. Total energy use per unit of product fell by 43% between 1996 and 2010. These kilowatts not used present savings for years to come.

To use more renewable energy, Interface undertook the following:

- Installed photovoltaics at the City of Industry, California factory

- Partnered with the local municipality to use landfill gas for the LaGrange, Georgia factory

- Installed photovoltaics at the factory in Scherpenzeel, Netherlands

- Installed photovoltaics at LaGrange.

Interface also purchases renewable energy from wind, solar and biomass projects directly from utilities where it is available. Where it is not, renewable energy credits are bought. Thus eight of Interface’s nine factories can be said to have 100% renewable electricity. (The five of these eight located in the U.S. rely heavily on renewable energy credits, but the three located in England, Ireland, and Holland rely solely on wind, biogas, and photovoltaics for electricity.)

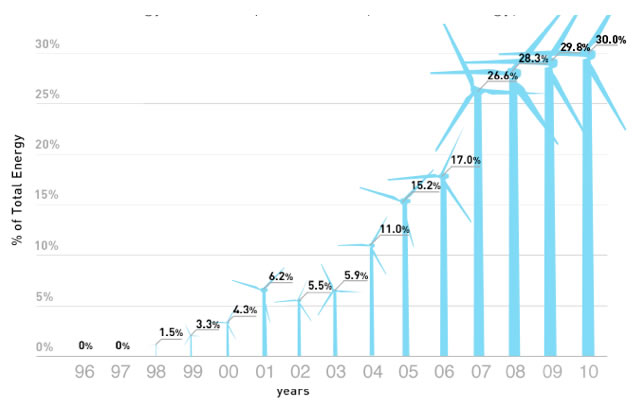

For total energy requirements (including other than electricity), 30% comes from renewables. Figure 2 shows progress over the years.

Figure 2. Renewable energy use at carpet factories (% of total energy) (Interface Carpet Company 2012)

Raw materials

To stop using virgin raw materials, Anderson reasoned, would require “harvesting the billions of square yards of carpets and textiles already made… using those precious organic molecules again and again in an endless cycle” (2009, p. 40). So far about 175 million pounds of carpet have been recycled. As of 2010, 40% of Interface’s raw materials were recycled or biobased. In 2007, the company became the first carpet manufacturer to implement a “clean separation” process (“ReEntry®”) to separate carpet fiber from its backing. The nylon fiber is returned to Interface’s supplier for reprocessing, and the backing material is reused into new backing with the “Cool Blue®” technology. Interface is able to manufacture products with 64% to 75% recycled content, including over 30% post-consumer recycled content.

Interface also switched from using virgin calcium carbonate to using aluminosilicate glass (a coal combustion byproduct) in producing carpet tile backing. And at “Supplier Summits” Interface encourages key suppliers to increase the recycled content of their products.

Transportation

To make transportation more eco-friendly, Interface selects the most efficient means of shipping available, e.g., using rail and ship, and avoids rush deliveries. For the company fleet, Interface works with Subaru to maximize efficiency—including “Partial Zero Emissions Vehicles” for the sales force. Subaru offsets the carbon footprint for the first 60,000 miles of company cars by purchasing and retiring carbon offsets, and the fleet uses “Cool Fuel”—gas with a carbon offset charge.

Employees who drive to work are encouraged to join the “Cool CO2mmute” program, in which the company shares the cost of sponsoring a tree planting program to offset carbon emissions. Similarly, Interface’s “Trees for Travel” program tracks and neutralizes carbon emissions from business-related air travel. Nearly 200,000 trees have been planted as a result of these programs.

Consulting

Interface Carpet created a consulting arm—InterfaceRAISE—to advise other businesses on going green. And Mr. Anderson travelled around the world to spread his message to a variety of audiences. His 2009 speech for TED on the business logic of sustainability can be viewed on YouTube [link http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iP9QF_lBOyA].

McDonald’s

According to its website (aboutmcdonalds.com), McDonald’s has collaborated with over 25 environmental organizations around the world over the last two decades. Some of these collaborations resulted in only superficial changes, like rainforest artwork for happy meals. But others are more significant. For instance, according to its “partner timeline:”

- In 1990 McDonald’s USA and the Environmental Defense Fund formed a task force to find ways to reduce, reuse and recycle materials generated by restaurants, suppliers, and the distribution system.

- In 1992 McDonald’s became a founding member of the Buy Recycled Business Alliance, a business-to-business group dedicated to increasing purchases of recycled products.

- In 1993 McDonald’s joined as official participant of Green Lights, a program aimed at promoting energy efficiency through investment in energy-saving lighting.

- In 2001 Conservation International helped McDonald’s develop its Sustainable Fisheries Program.

- In 2002 McDonald’s Europe worked with World Wildlife Fund to create its sustainable forestry policy.

- In 2005 McDonald’s partnered with Conservation International to develop its Supplier Environmental Scorecard.

- In 2006 in cooperation with Greenpeace International McDonald’s joined a moratorium on sourcing soya grown illegally in the Amazon biome.

- In 2007 McDonald’s became one of 25 members of the Sustainable Agriculture Initiative, the main food industry initiative supporting the development of sustainable agriculture worldwide.

- In 2009 the Japan Ministry of the Environment and McDonald’s Japan partnered to install LED lighting in over 30 restaurants, reducing energy consumption by 44%.

- In 2010 McDonald’s worked with World Wildlife Fund to complete the first assessment of its Sustainable Land Management Commitment and was a leading sponsor of the Global Conference on Sustainable Beef. Also that year McDonald’s USA partnered with RecycleBank in rewarding consumers for taking environmentally preferred actions.

According to its 2011 Global Sustainability Scorecard, McDonald’s’ sustainability strategy has five focus areas: Nutrition & Well-Being, Sustainable Supply Chain, Environmental Responsibility, Employee Experience, and Community. Of these, Sustainable Supply Chain and Environmental Responsibility are most relevant here.

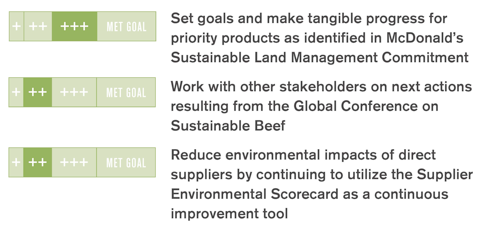

Sustainable Supply Chain

McDonald’s’ 2011 Global Sustainability Scorecard notes that 99% of its fish now comes from Marine Stewardship Council-certified fisheries. In Europe it is 100%, and all the filet-o-fish sandwich boxes are adorned with the MSC seal of approval. The company is working toward a goal of finding sustainable sources of beef, poultry, coffee, palm oil, and fiber as well. To this end the Supplier Environmental Scorecard was developed as a “continuous improvement tool.” Figure 3 shows progress on McDonald’s’ Sustainable Supply Chain goals.

Figure 3. Progress on Sustainable Supply Chain goals (McDonald’s 2011)

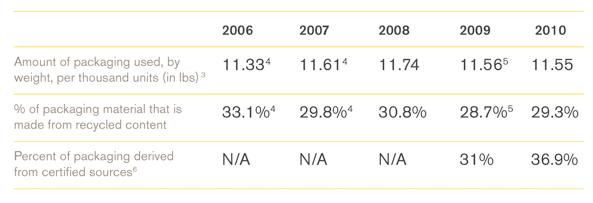

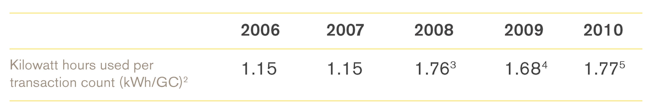

One obvious change is the switch from styrofoam containers to cardboard boxes with 37% post-consumer recycled content. But the company has little hope of recycling the huge amount of waste generated by its restaurants, since it is heavily contaminated with food residues. Table 1 shows statistics on consumer packaging, which actually seem to have gotten worse in the period 2006-2010.

Notes:

4 Not including China

5 Not including Brazil

Table 1. Characteristics of McDonald’s consumer packaging (McDonald’s 2011)

While McDonald’s can encourage suppliers to be more sustainable, it has no direct control over them. McDonald’s ranks #294 on Newsweek’s green ranking of America’s 500 largest businesses, but its biggest supplier, Archer-Daniels-Midland, ranks #495.

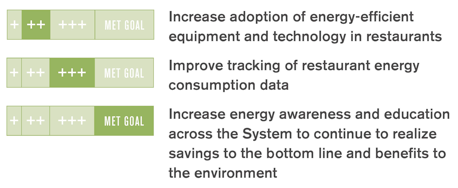

Environmental Responsibility

The area of Environmental Responsibility focuses mainly on energy use, and here McDonald’s’ Global Sustainability Scorecard highlights the fact that its 600 restaurants in Brazil underwent retrofits and reduced their energy costs to below 2007 levels, despite an increase in operating hours and energy prices. Worldwide, however, kilowatt-hours used per transaction count seems to have increased from 1.15 in 2006 to 1.77 in 2010. Figure 4 and Table 2 show progress on McDonald’s’ Environmental Responsibility goals.

Figure 4. Progress on Environmental Responsibility goals (McDonald’s 2011)

Notes:

3 Does not include data from Australia, Brazil or China. Restaurants for which data are reported represent approximately 19% of total restaurants as of December 31, 2008.

4 Does not include data from Australia, Brazil or China. Restaurants for which data are reported represent approximately 18% of total restaurants as of December 31, 2009.

5 Restaurants for which data are reported represent approximately 36% of total restaurants as of December 31, 2010.

Table 2. Energy usage in McDonald’s restaurants (McDonald’s 2011)

Walmart

Walmart happens to be a client of Ray Anderson’s consulting firm InterfaceRAISE; executives from Walmart and some of its suppliers participate in annual “Sustainability Summits” arranged by InterfaceRAISE. Walmart also hired Adam Werbach—former president of the Sierra Club and current CEO of Saatchi & Saatchi S—to advise its 1.4 million U.S. employees on sustainability. The Environmental Defense Fund, Natural Resources Defense Council, and World Wildlife Fund joined the campaign, reasoning that with 8,970 stores worldwide, Walmart could have a major impact on the world economy (Kroll 2012).

Similar to Interface Carpet Co., in 2005 Walmart’s CEO proclaimed three ambitious environmental goals:

- To be supplied by 100 percent renewable energy

- To create zero waste

- To sell products that sustain people and the environment

In 2010 the company added a goal of eliminating 20 million metric tons of greenhouse gas emissions from its supply chain by the end of 2015.

Energy

According to Walmart’s 2012 Global Responsibility Report, the company itself generates 1.1 billion kilowatt-hours of electricity from renewable projects, about 4% of its demand. Another estimated 18% renewables comes from the grid, for a total of 22% renewable electricity. When building energy needs other than electricity are included, about 15% of total energy is said to be renewable. Some gains have been made in energy efficiency as well. According to Anderson (2009, p. 169):

- In 2007, they [Walmart] opened three high-efficiency stores, called HE.1, that use 20 percent less energy than a typical supercenter.

- In January 2008, they opened the first of four next-generation high-efficiency stores (HE.2). This store is 25 percent more energy efficient than the 2005 baseline, and it has reduced refrigerant use by 90 percent.

Energy improvements were made to older stores as well, reducing consumption by an average of 10% per store. For its 200 top factories in China, Walmart set a goal of 20% improvement in energy efficiency per unit of production by the end of 2012. At the end of 2011, 148 factories had achieved that goal.

Concerning the problem of energy for transportation, Anderson (2009) notes that “As the owner of one of the largest private trucking fleets in the world, the company is partnering with truck manufacturers to radically improve its efficiency, as well as retrofitting its existing fleet with diesel-saving technologies” (p. 169-170). Walmart (2012) reports a 69% improvement in cases shipped per gallon burned in the U.S. for 2011 compared to a 2005 baseline. The goal is to double fleet efficiency by October 2015.

Waste

Walmart’s goal of eliminating landfill waste from operations at its U.S. stores and Sam’s Club locations is 80.9% complete and the company earned an estimated $231 million in recycling revenue and savings (Louie 2012). Plastic bag waste reportedly has been reduced by 35%. Baselines are being established for the goal of reducing food waste by 15% in “emerging market” stores and by 10% in all other markets (Walmart 2012). The amount of waste that consumers take home with them is another matter entirely. Walmart’s goals are to reduce packaging by 5% between 2008 and 2013, and to be “packaging neutral” by 2025—i.e., to switch to packaging that is recyclable, reusable, and made with recycled and/or sustainably sourced renewable content. According to the 2012 Global Responsibility Report, “significant progress is being made” and the company is “on track” toward this goal.

Sustainable products

In terms of selling products that “sustain people and the environment,” Walmart’s first step was to include language in all supplier agreements requiring them to declare compliance with relevant social and environmental regulations. It also distributed a sustainability questionnaire to over 100,000 of its suppliers.

Anderson (2009, p. 169-170) notes that:

- In May 2008, Wal-Mart achieved its goal to sell only concentrated liquid laundry detergent … saving 400 million gallons of water, 95 million pounds of plastic resin, and 125 million pounds of cardboard.

- Last year they sold 137 million compact fluorescent lamps … it prevents twenty-five million tons of carbon dioxide from being released. That’s the equivalent of taking one million cars off the road.

However, under its two “goals not met,” Walmart (2012) admits that its goals were to (a) reduce phosphates in laundry and dish soaps sold in the Americas by 70% between 2008 and 2011 (only a 43% reduction was achieved) and (b) to double the U.S. sale of products that make homes more efficient (there was a 33.5% increase).

In the area of produce, Walmart adopted a “direct farm” program to source more foods from local small- and medium-sized farmers, and plans to undertake a farmer training program in sustainable agricultural practices. In the U.S., Walmart nearly achieved its goal of doubling the sales of locally sourced produce (i.e., within the same state), but the total still only amounts to 10% of produce sold. The company also hopes to achieve sustainability certification for sources of palm oil, beef, and fish by 2015. Currently only one particular brand of banana nut bread is Sustainable Palm Oil certified; 76% of Walmart’s seafood suppliers are certified.

Walmart is in the process of developing a sustainable product index. The first step was the aforementioned supplier sustainability questionnaire. The second step is to develop a product lifecycle analysis database—from raw materials to disposal—with the help of The Sustainability Consortium. These two elements will be combined into an easy-to-understand rating, like calorie counts on today’s food packaging, to help both suppliers and shoppers make greener choices.

Greenhouse gases

As for the goal of eliminating 20 million metric tons of greenhouse gas emissions from the global supply chain by 2015, 120,000 metric tons have been eliminated so far—only 0.6% of the goal.

Newsweek gave Walmart a green ranking of #52 on its list of 500 biggest U.S. companies. But Stacy Mitchell of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance complains that the media focus on Walmart’s accomplishments without giving the proper context—a “PR boost [that] has enabled Walmart to accelerate the pace of its expansion.” For instance,

- The media focus on Walmart’s goal of 100% renewable energy, which has no timeframe, instead of the fact that less than 2% of its energy is self-generated renewables. The number is not higher because of corporate greed: further investments do not meet the company’s “ROI [return on investment] requirements.” Walmart’s energy efficiency savings are dwarfed by the energy consumed by hundreds of new stores built each year. The 200 top factories in China that were to achieve a 20% reduction in energy consumption represent less than 1% of its factories in that country.

- In terms of waste, Walmart sells shoddier products and “speeds the flow of goods from factory to landfill.”

- The Sustainability Consortium was created by Walmart to develop the product sustainability index and is dominated by business interests and administered by educational institutions that have ties to Walmart’s founder. The sustainability questionnaire distributed to its suppliers is superficial and unverified. With its increasing share of the grocery market since 1988, Walmart is taking over and transforming our food system for the worse.

- Walmart ignores its biggest climate impact: sprawl. The company never mentions its impact on land use patterns and household driving, as it destroys local economies (Mitchell 2012).

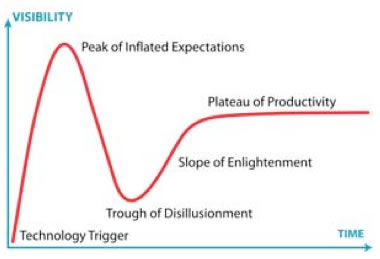

Michelle Harvey of Environmental Defense Fund, which has worked with Walmart since 2005, notes Walmart is following the Gartner Hype Cycle, with its “peak of inflated expectations” followed by a “trough of disillusionment” (see Figure 5). For instance, regarding Walmart’s quest for accurate raw-material-to-final-disposal product footprints (the sustainable product index), “after two years, when everything wasn’t done, when the sustainability scores of every product weren’t known and being shared with customers, the buzz turned sour and disparaging comments piled up. … It appeared at times that they were backing away from sustainability. Projects started and stopped. Sustainability messaging got softer, and sometimes seemed to disappear. Walmart moved slower than we knew they could.” But she insists the new product category scorecard is well underway and will influence Walmart’s buying decisions; the “slope of enlightenment”—the next stage of the hype cycle—is near.

Figure 5. The “hype cycle” (Harvey 2012)

Investigative journalist Andy Kroll went to China for a firsthand look at the effort to reduce energy consumption by 20% at the country’s 200 top Walmart factories. He found the project to be basically dormant, mainly because the Environmental Defense Fund quit. A bigger problem is that Walmart’s 30,000 Chinese factories have sub- and sub-sub-suppliers, or “shadow factories” that are very difficult to trace, much less convert to sustainable enterprises. His article is subtitled “Walmart wants you to believe its green makeover is changing the world. Just one hitch: China” (Kroll 2012).

Creating New Green Businesses

According to LOHAS (lohas.com), the U.S. “Lifestyles of Health and Sustainability” market, with over 40 million consumers, presents a largely untapped $290 billion in business opportunities, as follows:

- Personal health - $117 billion

- Green building - $100 billion

- Eco tourism - $42 billion

- Alternative transportation - $20 billion

- Natural lifestyles - $10 billion

- Alternative energy - $1 billion (renewable energy systems are included under green building)

LOHAS offers education and networking through its newsletter, journal, forums, and business directory for companies that cater to the LOHAS-oriented consumer.

Scott Cooney (2009) has compiled a practical how-to guide for a wide range of green business ideas. For readers who may be interested, the entire table of contents is reproduced here:

- Dry Cleaning Services and Laundromats

Eco-Laundromat

Alternative Dry Cleaning Service - Ecotourism and Related Services

Ecotour Operator

Ecotransport Rental Operation

Green Bed & Breakfast - Entertainment and Events

Organic Foods Caterer

Wedding and Event Planner - House and Office Services

Carpet and Floor Cleaning

Floor Installation

Home and Office Cleaning

Landscape Design

Lawn Mowing and Landscape Maintenance

Organic Garden Creation and Maintenance

Painting

Pool and Spa Cleaning and Maintenance - Manufacturing and Wholesale Production

Biodiesel Cooperative

Gift Basket Service

Organic Community-Supported Agriculture - Personal Services

Fitness Training and Diet Planning

Green Real Estate Brokerage

Green Shuttle Services

Organic Food Delivery Services

Organic Day Spa

Travel Planning - Publishing and Related Businesses

Environmental Freelance Writer

Green Product Catalog Producer

Publication Distribution Service - Retail Food and Food Services

Free-Range, Organic Fresh-Mex Restaurant

Organic Coffee Shop

Organic Juice and Smoothie Bar

Organic Pizzeria

Raw Food Bar

Sustainable Buffet-Style Restaurant

Vegan Café - Retail Nonfood Operations

Alternative Transportation Retail Store

Aveda Concept Salon

Bike Shop

Consignment Store

Edible and Organic “Floral” Arrangements

Green Building Supply Store

Green Product Retail Store

Native and Organic Plant Nursery

Printer Cartridge Refilling Store

Used-Book Exchange - Services to Businesses and Nonprofit Organizations

Fundraiser and Grant Writer

Independent Publicist

Independent Sales Representative

Restaurant Delivery Service

Specialty Advertising

Sustainability Consultant - Other Types of Green Businesses

Carbon Offsets

Environmentally Themed E-business

Green Venture Capitalist

Sustainable Remodeling and Flipping Houses

Cooney’s website, greenbusinessowner.com, provides further up-to-date information, including financing opportunities.

Also helpful is the federal Small Business Administration’s new Green Business Guide. It includes sections on green marketing, green business case studies, green business practices, certification and ecolabeling, and product development, among others. See http://www.sba.gov/category/navigation-structure/starting-managing-business/managing-business/running-business/green-business-guide

Besides offering green goods and services, according to Hawken (1993), businesses must replace nationally and internationally produced items with products created locally and regionally. They should not require exotic sources of capital. This is closely related to what economist David Korten (2009, 2012) calls “local living economies,” which better mimic natural systems in organizing local resources to meet local needs. Korten is on the board of the Business Alliance for Local Living Economies (livingeconomies.org), a network of over 22,000 small businesses organized into over 80 community networks in 30 U.S. states and Canadian provinces. With the building blocks of sustainable agriculture, green building, renewable energy, community capital, zero-waste manufacturing, and independent retail they strive toward “local living economies that function in harmony with local ecosystems, meet the basic needs of all people, support just and democratic societies, and foster joyful community life.”

Conclusion

So what is the state of green business in America today? Suffice it to say the revolution is not complete. We are on the right track, but have a long way to go in creating anything resembling a “restorative” economy.

According to Adam Werbach (2012), the corporate sustainability movement seems to have stalled. The “low-hanging fruit” ran out; the financial crisis struck; the regulatory framework weakened; energy prices stabilized; there is a lack of urgency. The latest State of Green Business report (Makower et al. 2012) shows some discouraging results. Positive trends continued for:

- clean energy patents

- e-waste recycling

- electricity from renewables

- sales of organic food

But positive trends were reversed in the last year for:

- toxic chemicals used per billion dollars of GDP

- paper used per billion dollars of GDP

- hazardous emissions per billion dollars of GDP

- energy use per billion dollars of GDP

- packaging materials per million dollars of GDP

- cleantech investments

- greenhouse gas emissions per vehicle

It seems unlikely that multinational corporations with long supply chains selling disposable goods can ever be good for the environment. Nor can a whole economy based on producing an overabundance of things people do not really need. There is more hope in the “new economy” some see emerging. New businesses are more localized and socially conscious. Alternatives to the traditional capitalist model are emerging, as more Americans become involved in cooperative enterprises or create their own jobs. Detroit is a prime example, where the shrinking population has taken up urban farming (Joyce 2012). There is hope too in the field of education, where more business schools are including sustainability in the curriculum. Chief financial officers are increasingly using triple bottom line accounting. Perhaps Anderson’s “new Economics 101” is emerging.

But more effort is needed in changing the fundamental framework in which American business operates. For far too long, “the expense of destroying the earth is largely absent from the prices set in the marketplace” (Hawken 1993, p. 13). The government could conceivably address that pricing problem with, e.g., taxes reform and fees. It could try alternative measures to gross domestic product—e.g., Maryland’s Genuine Progress Indicator—to recognize that consumption is not the same as well-being.

The government could also shift its spending priorities to create a more restorative economy. Van Jones, the federal “green jobs czar” in March-September 2009, envisioned a Green New Deal in which government subsidies are shifted from fossil fuels and wars to renewable energy and environmental restoration. “Right now,” he says, “the public sector gives most of its love, respect, and money to the problem makers in our economy: the war makers, polluters, and incarcerators. They all get billions and billions of dollars in tax breaks and direct subsidies, while the renewable sectors—the job creators of the future—still get pennies.” A “green-collar economy” could solve our two biggest problems—the economy and the environment—simultaneously (Jones 2008). It is time to “propose solutions at the scale of the problems we face.” We need a new economy that is based on:

- production instead of consumption

- thrift instead of credit

- ecological restoration instead of ecological destruction (Jones 2012).

Over the years a number of comprehensive plans have emerged for creating a sustainable economy, such as Herman Daly’s Steady-State Economics, Lester Brown’s Eco-Economy, Paul Hawken et al.’s Natural Capitalism, Gus Speth’s Charter for a New Economy (and forthcoming Roadmap to a New Economy). They are all worthy of consideration and implementation, but that is beyond the scope of this report. In any case, they will need the wholehearted cooperation of American business to succeed.

References

Anderson, Ray C. with Robin White. 2009. Confessions of a Radical Industrialist: Profits, People, Purpose—Doing Business by Respecting the Earth. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Brown, Lester R. 2001. Eco-Economy: Building an Economy for the Earth. New York: W. W. Norton.

Cooney, Scott. 2009. Build a Green Small Business: Profitable Ways to Become an Ecopreneur. New York: McGraw Hill.

Daly, Herman E. 1991. Steady-State Economics (2nd ed.). Washington: Island Press.

Harvey, Michelle Mauthe. 2012. Where is Walmart on the ‘Hype Cycle’? Website http://www.greenbiz.com/blog/2012/03/30/where-walmart-hype-cycle

Hawken, Paul. 1993. The Ecology of Commerce: A Declaration of Sustainability. New York: HarperCollins.

Hawken, Paul, Amory Lovins and L. Hunter Lovins. 1999. Natural Capitalism: Creating the Next Industrial Revolution. New York: Little, Brown & Co.

Interface Carpet Company. 2012. Our Progress. Website http://www.interfaceglobal.com/Sustainability/Our-Progress.aspx

Jones, Van. 2012. After Financial Collapse, A New, Green Economy. Solutions Journal 3(3). Website http://www.thesolutionsjournal.com/node/1110

Jones, Van with Ariane Conrad. 2008. The Green-Collar Economy: How One Solution Can Fix Our Two Biggest Problems. New York: HarperCollins.

Joyce, Frank. 2012. Is It Possible To Build An Economy Without Jobs? Alternet, April 30. Website http://www.alternet.org/story/155186/is_it_possible_to_build_an_economy_without_jobs

Korten, David. 2009. Agenda for a New Economy: From Phantom Wealth to Real Wealth. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Korten, David. 2012. Interview for Spring of Sustainability, April 18. Website http://springofsustainability.com/

Kroll, Andy. 2012. Walmart’s Shadow Factories. Mother Jones March/April, p. 36-44.

Louie, Eric. 2012. Walmart creeps forward on its sustainability goals. Website http://www.greenbiz.com/blog/2012/04/16/walmart-sustainability-report-2012

Lu, Cecilia. 2010. Corporate Social Responsibility’s Seven Best Practices: Avoid Greenwashing Through Stakeholder Engagement. GLOBE-Net online, July 13 Website http://www.globe-net.com/articles/2010/july/13/corporate-social-responsibility%E2%80%99s-seven-best-practices/

Makower, Joel and the editors of GreenBiz.com. 2012. State of Green Business 2012. Website http://www.greenbiz.com/research/report/2012/01/state-green-business-report-2012

McDonald’s Corporation. 2011. McDonald’s 2011 Global Sustainability Scorecard. Website http://www.aboutmcdonalds.com/content/dam/AboutMcDonalds/Sustainability/Sustainability%20Library/2011-Sustainability-Scorecard.pdf

Mitchell, Stacy. 2012. Walmart’s Greenwash: How the company’s much-publicized sustainability campaign falls short, while its relentless growth devastates the environment. Institute for Local Self-Reliance. Website http://www.ilsr.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/walmart-greenwash-report.pdf

Newsweek Green Rankings. Website http://www.thedailybeast.com/newsweek/features/green-rankings/2011/us.html

Speth, Gus. 2012. For Rio+20: A Charter for a New Economy. Solutions Journal 3(3). Website http://www.thesolutionsjournal.com/node/1106

Sullivan, Thomas F.P. (ed.). 1992. The Greening of American Business: Making Bottom-Line Sense of Environmental Responsibility. Rockville, MD: Government Institutes Inc.

Walmart. 2012. Beyond 50 years: Building a sustainable future (Walmart 2012 Global Responsibility Report). Website http://www.walmartstores.com/sites/responsibility-report/2012/pdf/WMT_2012_GRR.pdf

Werbach, Adam. 2012. Interview for Spring of Sustainability, April 24. Website http://springofsustainability.com/

Useful websites

Business Alliance for Local Living Economies

Lifestyles of Health and Sustainability

Small Business Administration Green Business Guide