EcoTipping Points

- How do they work?

- Leveraging vicious

cycles to virtuous - Ingredients for success

- Create your own

EcoTipping Points!

Stories by Region

- USA-Canada

- Latin America

- Europe

- Middle East

- South Asia

- Southeast Asia

- East Asia

- Africa

- Oceania-Australia

Stories by Topic

- Agriculture

- Business

- Education

- Energy

- Fisheries

- Forests

- Public Health

- Urban Ecosystems

- Water and Watersheds

Short Videos

- Saving a Coral Reef and Fishery (Apo Island, Philippines)

- Community Gardens Reverse Urban Decay (NYC, USA)

- Community Forests Reverse Tropical Deforestation (Thailand)

- Escaping the Pesticide Trap (India)

- Rainwater Harvesting and Groundwater Replenishment (Rajasthan, India)

How Success Works:

- Saving a Coral Reef and Fishery (Apo Island, Philippines)

- Community Gardens Reverse Urban Decay (NYC, USA)

- Community Forests Reverse Tropical Deforestation (Thailand)

- Escaping the Pesticide Trap (India)

- Rainwater Harvesting and Groundwater Replenishment (Rajasthan, India)

Human Ecology:

Principles underlying

EcoTipping Points

He‘eia Fishpond and Watershed

Author: Regina Gregory

Special thanks: Christy Mishina

Posted: December 2015

Hawaiians divided their land by ahupua‘a, roughly translated as watersheds. Resources were managed in an integrated way from the mountaintop to the outer edge of the reef, and everyone had access to whatever they needed. This concept is slowly making a comeback, and the ahupua‘a of He‘eia is one example. Restoration of the coastal fishpond, and various upstream projects to restore the ecosystem, are described. Detailed ecotipping points analyses by seven students are presented in the Appendix.

Sometime between the years 300 and 1200 A.D., Polynesians sailed across the Pacific and settled on the islands of what we now call Hawai‘i. With the basic philosophy of working with nature to create abundance, and conserving the productivity of resources in perpetuity, they developed a food system that was totally self-sufficient and sustainable. Early European explorers marveled at the large population and the high productivity of the land. But in just 230 years, Hawai‘i changed from totally self-sufficient to about 90% dependent on imports for food. A movement is underway to reverse the loss; remnants of taro patches (lo‘i kalo) (see related story) and fishponds (loko i‘a) are helpful guides.

According to Kelly (1975), the difference between Hawaiian modifications to the environment and modern economic development is not just a matter of degree, but a different set of values. The desire to be pono (good, righteous) is one essential element for a “modern ahupuaʻa” to succeed. It is reinforced by education. The other two essential elements are community organizing and holistic management (Kittinger 2013).

Fishponds in Hawai‘i

Hawaiians developed a unique system of aquaculture that is “one of the most significant and successful aquacultural achievements in the world” (Farber 1997, p. 1). Beginning around 1,200 years ago, Hawaiians built nearly 500 fishponds on the islands. A watershed with one or more fishponds was considered “fat” (momona) and prosperous.

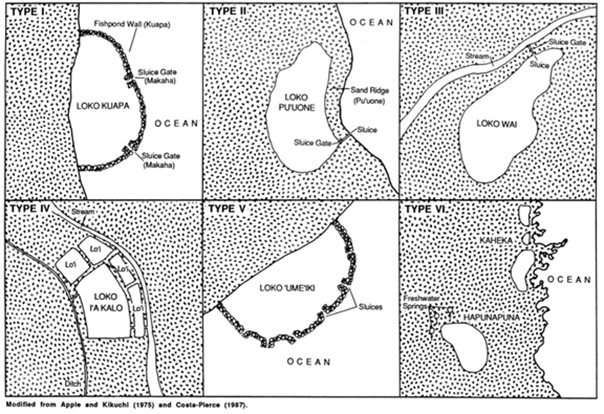

There are six basic types of fishpond, as shown in Figure 1. The first three types (kuapā, pu‘uone, and loko wai) were “royal,” i.e., owned by and for the use of ruling chiefs. It is thought that by feeding the chiefs from fishponds, more fish were left in the open ocean for commoners to catch; also, a well-fed chief would demand less “taxes” (i.e., food and other natural products) from the residents of his ahupua‘a (Apple & Kikuchi 1975, Keala 2007).

Figure 1. Hawaiian fishpond types

Source: DHM Planners 1989

Sluice gates (mākāhā) on Types I, II, and III are made of poles lashed together so that water can come in and out. The poles are spaced so that juvenile fish can enter the pond, but when they grow larger they cannot come out. Mature fish ready to go back to the ocean would gather at the gates and be easily caught.

Types I, II, and V are brackish water ponds, that is, they contain a mixture of freshwater and saltwater. The brackish water suits the taste of young fish in the ocean. They swim into the pond and are trapped. Besides brackish water, the fishpond must also have the right kind of algae to lure in the young fish and feed them. Pond depth must also be maintained so the water is deep enough to keep fish cool, but shallow enough for the algae to get enough sunlight.

Depending on intensity, a fishpond can yield hundreds or thousands of pounds per acre (Wyban 1991). The reliance on herbivorous fish makes it especially efficient: According to Henry (1993), in the natural food chain, 10,000 pounds of algae produces 1 pound of man. In the Hawaiian fishpond food chain, 10,000 pounds of algae produces 100 pounds of man.

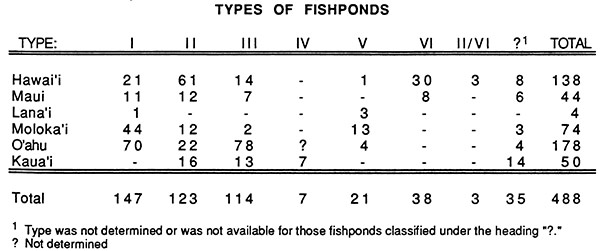

DHM Inc. (1989, 1990) cataloged 488 fishponds in the Hawaiian Islands, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Fishponds in Hawai‘i, by island and type

Source: DHM Inc. 1990

Currently, only about a dozen fishponds are functioning as intended. Twenty-five of the 488 are in good-to-excellent condition, 97 are in fair-to-good condition, and the rest are in poor condition or gone entirely (DHM Inc. 1990). Fifty-six were deemed potentially useful (6 excellent, 15 good, and the rest fair or poor) (Keala 2007).

Many factors contributed to the decline of Hawaiian fishponds, beginning with the arrival of Captain Cook in 1778:

- Western diseases decimated the local population.

- Land ownership was privatized and the tradition of sharing and cooperating broke down.

- The market economy replaced the subsistence economy; money, instead of food production, became the main measure of success.

- Water was diverted by sugarcane plantations.

- Sedimentation—from both agricultural and urban development—polluted the water.

- People left the land to live in cities.

- The number of local fish markets fell.

- Invasive alien plant and animal species were introduced.

- Ponds were filled to create more land for development.

- Fishpond caretakers died.

- Without maintenance, natural forces cause fishpond deterioration.

But many fishponds are being restored. The future looks brighter because of:

- Enthusiasm of the younger generation (“young Hawaiians with a lot of energy,” according to Hi‘ilei Kawelo) to restore their culture and local self-reliance, coupled with the fact that some elders are still alive to explain traditional resource management.

- A shift in state policy which streamlines the permitting process for fishpond restoration—“the most frustrating, time-consuming, and costly aspect of fishpond restoration and revitalization projects” (Keala 2007, p. 5). Before, rebuilding a fishpond required just as many permits as, e.g., a resort with a marina.

- A state master plan to restore Kāne‘ohe Bay (Office of State Planning 1992).

- The Governor’s task force on fishpond restoration.

- A shift in landowner policy (in this case, Kamehameha Schools, the state’s largest private landowner) to consider values other than maximum profit.

- Organization: The Hui Mālama Loko I‘a—a growing network of fishpond practitioners and allies who share knowledge and resources—now includes over 100 people from 38 fishponds (kuahawaii.org).

He‘eia Fishpond

The 88-acre He‘eia Fishpond was built 600-800 years ago by the residents of the He‘eia watershed. He‘eia is located on Kāne‘ohe Bay on the northeast shore of the island of O‘ahu, the district called Koʻolaupoko (see Figure 2). This is the “windward side” and prevailing winds rise up the Ko‘olau Mountains and create a large amount of rainfall. Often the cliffs sport waterfalls. Especially heavy rains cause “pulse events” of 5,000-6,000 cubic feet per second of water flowing through the watershed. These events are expected to become more frequent with climate change (Kanekoa Kukea-Shultz, interview 9/23/14). The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has named He‘eia a “Sentinel Site” where climate change mitigation and adaptation are studied. So far it is the only Sentinel Site where “past management and past practices” are considered part of the solution (Leong 2013).

Figure 2. He‘eia Fishpond

Photo: Manuel Mejia, The Nature Conservancy of Hawai‘i

He‘eia Fishpond is a loko kuapā (Type I) pond. Its wall is extraordinary: it is 12-15 feet wide and consists of two lava rock walls with a layer of coral between. Unlike other kuapā-type ponds, the wall forms a complete circle rather than a semi-circle. It is possibly the longest fishpond wall in Hawai‘i, 7,000 feet long. He’eia Fishpond has six sluice gates—three along the seaward edge that regulate salt water input and three along He‘eia stream that regulate fresh water input. Fish that live in the pond include ‘ama‘ama (mullet), awa (milkfish), pualu and palani (surgeonfish), āholehole (mountain bass), moi (threadfin), kōkala (porcupine fish), kākū (barracuda), and pāpio (trevally). The fishpond is also home to different species of pāpa’i (crab), ‘ōpae (shrimp), puhi (eel), and pipi (oyster) (paepaeoheeia.org). It is thought that the pond once produced 200 pounds of fish per acre per year (Koani Foundation 2014).

He‘eia Fishpond’s early history is unclear, but it is known that at the time of the Great Māhele (land division) of 1848, Abner Pāki was the chief of He‘eia and he was awarded the entire watershed, including the fishpond.1 Pāki’s daughter, Princess Bernice Pauahi Bishop, inherited the land. It is still part of Bishop Estate (now known as Kamehameha Schools) (paepaeoheeia.org).

As the socioeconomic system changed, oversight of the fishpond changed from appointed guardians (kia‘i loko) to paying lessees. The Au family leased the pond until the floods of 1921 damaged the wall. They sold the lease to the Hee family. Flooding in 1927 also damaged the wall and was repaired by the Hee family (Kelly 1975). According to Henry (1993), in 1930 Hau Hee took over from his father and implemented some innovations, such as subdividing the pond and experimenting with fish propagation. He fed the young mullets middling and bran every day and caught fish only from April to October, leaving them to spawn the rest of the year. During the season, Hee took an average of 100 pounds a day to his stall at the fish market, not only mullet but also āholehole (mountain bass), weke (goatfish), and awa (milkfish). Hee also experimented with growing shrimps. He employed five men most of the year, and 12-15 when there was extra work to be done.

In 1948, Bishop Estate hired a consultant for the development of He‘eia. Initially a residential community of 30,000-40,000 homes was planned, along with a marina replacing the fishpond. In 1964 a golf course was added to the plan. But in 1973, He‘eia Fishpond was selected as a U.S. National Historic Site and the pond was rezoned from urban to conservation. In addition, the community had protested against the planned large-scale land development, and in the early 1980s the plans were abandoned. The State of Hawaii purchased the peninsula next to He‘eia Fishpond as a state park, and made plans to also acquire the wetlands just south of the fishpond, but did not purchase the pond (Henry 1993).

In 1965 the devastating “Keapuka Flood” caused a 600-foot break in the river side and a 200-foot break in the ocean side of the fishpond wall, so that He‘eia Stream flowed directly into the pond, and fish could easily escape from the ocean side. The fishpond went mostly unused for almost 25 years after that. Invasive mangroves grew unchecked, further damaging the wall. Heavy siltation from the stream caused the pond to become too shallow, so that some of the bottom was exposed at very low tide (Brooks 1991, Henry 1993).

In 1988, former state aquaculture extension agent Mark (later Mary) Brooks leased the pond, and for the next two years he and volunteers worked on repairing the hole in the ocean side. Being very budget-conscious, Brooks used mostly free materials, e.g., cement test cylinders about 6 inches in diameter and 1 foot long (Brooks 1991, Henry 1993). Brooks was successful at raising ‘amaʻama (mullet), moi (threadfin), tilapia, and ogo (seaweed), and experimented with other aquaculture ventures (paepaeoheeia.org).

In 2000, Brooks taught the first “Mālama Loko I’a” (Take Care of the Fishpond) class at the University of Hawaii – Mānoa. Former student Hi‘ilei Kawelo recalls, “we had class on Fridays at UH, a lecture. The lab was all day here [at the fishpond] on Saturdays, and the large majority of what we did was cut mangroves, every Saturday” (interview 8/14/14). This was the beginning of the pond’s current restoration. Kawelo and eight other young Hawaiians formed Paepae o He`eia the following year. The organization now works on a fee-for-service basis with Kamehameha Schools to manage and maintain He‘eia Fishpond for the community (paepaeoheeia.org). Kawelo is the executive director. In 2010 Kamehameha Schools replaced the aging lessee’s house on the bank of the pond with a nice new one. It is now the home of caretaker and master fishpond builder Peleke Flores.

Paepae o He‘eia’s main programs include restoration, education, and production.

Restoration

According to Paepae o He‘eia’s website, the fishpond’s restoration has three steps, which are going on simultaneously in different sections. Step one of the restoration process is removal of mangrove that has taken root on the wall. The mangrove roots loosen the wall’s rocks and destroy its structural integrity. As mentioned above, this began in the late 1990s with pond lessee Mary Brooks and students from the University of Hawai‘i. Over the years since then, thousands of volunteers have joined in the effort.

Step two is rebuilding the wall with the traditional Hawaiian dry-stack method. To date about half (3,500 of 7,000 feet) of the wall has been completely restored. After a long wait, a federal permit to close the remaining 80-foot hole on the ocean side was granted. Rather than hire a contractor, Paepae o Heʻeia chose to make this a community-building project (Hi‘ilei Kawelo, interview 8/14/14). The organization raised $100,000 for its “Pani ka Puka” (Close the Hole) project and called for 1,000 people to come on December 12, 2015 to form a line and pass rocks like their ancestors did. About 2,000 people came, including the Governor of Hawaiʻi, and formed a 2,000-foot-long line. They passed thousands of pounds of lava rocks and coral, as well as two new sluice gates, down the line and now—50 years after the Keapuka Flood—the hole is finally repaired.

Figure 3. Volunteers help rebuild the fishpond wall

Photo: Paepae o He‘eia

Step three is invasive seaweed removal. Paepae o He‘eia has been removing seaweed since 2004 with the help of The Nature Conservancy, the state Division of Aquatic Resources, the Oʻahu Invasive Species Council, and volunteers.

Paepae o He‘eia’s nine staff members work all week. Volunteers are welcomed every Friday morning, and on the second and fourth Saturdays of every month. Every year 7,000-8,000 people come to help.

Education

Eco-cultural education is one of Paepae o He‘eia’s principle products—its “bread and butter,” according to Kawelo. It is fortunate timing that Hawaiian charter schools became popular around 2001. Paepae o He‘eia has partnered with Hawaiian charter schools to use the fishpond as an outdoor classroom and lab. Every Thursday, for instance, 7th graders from Hālau Kū Māna come to the fishpond for science and math credit. The outdoor setting makes it much more interesting for students. They are happy to be there instead of in a classroom, and the fishpond offers a practical combination of oceanography, biology, chemistry, math, physics, and engineering (Koani Foundation 2014). But the most important lesson is mālama ‘āina (take care of the land).

Every Monday through Thursday Paepae o He‘eia hosts one-hour walking tours and three-hour field trips. Prices range from $20 for a walking tour for one to four people to $500 for a field trip for 70-80 people. The field trips include a service learning project and educational lessons that can be subject-specific if requested. Mostly 4th and 6th graders from public schools attend the field trips, but the range is from preschool to adult. Every year about 3,000 students visit the fishpond, and they contribute to the volunteer labor force as well (paepaeoheeia.org, Koani Foundation 2014).

Figure 4. Students helping with algae removal at the fishpond

Source: paepaeoheeia.org

Naturally students from Kamehameha Schools, the owner of the fishpond, also come to learn. Kamehameha teacher Christy Mishina (a long-time fishpond volunteer) brings her 7th grade class every year. In 2014, as a Ph.D. student in Sustainability Education, Mishina taught a special lesson about ecotipping points. The students wrote eloquently about the fishpond’s negative and positive tipping points and evaluated its adherence to the 10 “ingredients for success” (see explanation). Seventy-five percent of the students agreed that He‘eia Fishpond is a successful ecotipping points story (49% strongly agreed and 26% somewhat agreed) (Mishina 2014). Seven of the students’ ecotipping points analyses are presented in the Appendix.

At the University of Hawai‘i, the fishpond class mentioned above is still taught one semester per year—Hawaiian Studies 353, Mālama Loko Iʻa. Its description reads, “Study of traditional Hawaiian fishpond management with hands-on experience at He‘eia fishpond near Kāneʻohe, merging traditional Native knowledge and ways of seeing with Western science” (www.hawaii.edu).

Paepae o He‘eia also offers a paid internship—the He‘eia Ahupua‘a Internship. Participants learn important skills not only in the fishpond but also in the taro patches upstream (paepaeoheeia.org).

In addition, Paepae o He‘eia hosts occasional special programs in the evening. For instance, March 13, 2014 was keiki (children) night with stories about the history of the area and crafts. On June 19 there was a “talk story” with fishpond restoration expert “Uncle Buddy” Keala (paepaeoheeia.org).

Besides education, the fishpond is the site of much research by entities such as the state Division of Aquatic Resources, NOAA, various universities, and The Nature Conservancy. Research topics include water quality, water flow, sediment chemistry, invasive algae and native algae, bivalves, and microbes. Further support is provided by a collaboration between Paepae o He‘eia and the Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology. It offers six 6-month paid research internships in which students focus on “the biological and geological processes in the fishpond, integrated with eco-cultural knowledge and practices.” Research continually improves the knowledge base that guides Paepae o He‘eia’s management strategies (paepaeoheeia.org).

Production

The most valuable fish in He‘eia Fishpond is moi (Pacific threadfin). It was once eaten only by Hawaiian royalty. Availability is seasonal. When available, moi are sold during one-day sales at the fishpond or to restaurants. At the 2006 “Moi and Poi” event, 800 pounds, at $8.00 per pound, was sold out in just 45 minutes. Many people went away disappointed, but the event raised awareness and enthusiasm about the fishpond (Keliʻi Kotubetey, interview 8/14/14).

Unfortunately, 2010 was an El Niño year. The water temperature was too high, resulting in low dissolved oxygen, and all the fish died. A new project is to raise mullet in large pens. Baby mullet were obtained from the Oceanic Institute, and it is hoped that within three years they will be ready for harvest (Keliʻi Kotubetey, interview 8/14/14).

The invasive algae that is being removed, “gorilla ogo,” is edible and is sold at $3.00 per pound. Paepae o He‘eia also gives seaweed to local farmers for fertilizer.

Two species of oysters live in the pond. Their viability as a commercial product is being researched and appears encouraging.

Mangrove wood (for firewood and construction material) is given away for free (paepaeoheeia.org).

A possible question for future research is how to increase the number of fish in the sea to populate the fishpond.

The He‘eia Watershed

Even all that work at the fishpond is not enough, because the fishpond will only be as healthy and productive as the rest of the watershed (Sanburn 2014). Luckily, Kawelo’s friends from college formed nonprofit organizations upstream and together they work as Hanohano He‘eia.

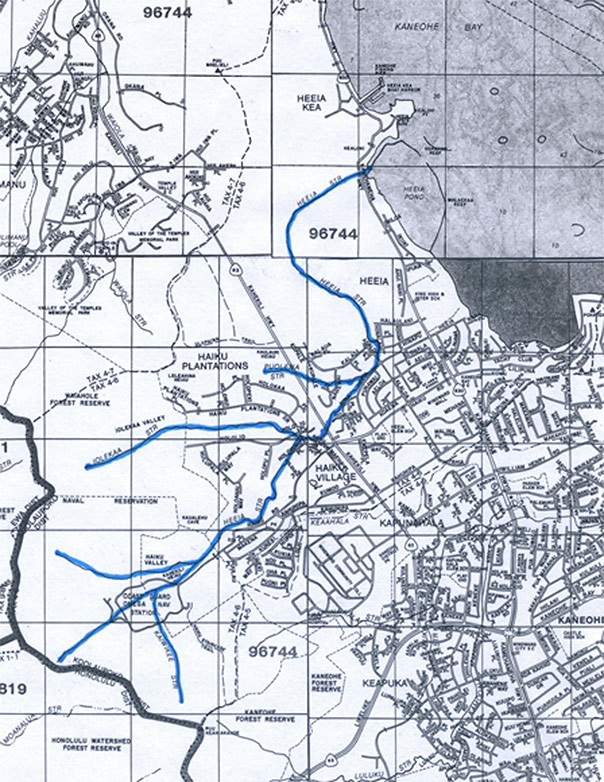

Figure 5 shows a map of He‘eia Stream and its tributaries from the mountain to the fishpond. One can see from this and from Figure 2 that the watershed straddles the border between “town” and “country,” and much of it is urbanized.

Figure 5. Map of He‘eia watershed

Source: Bryan’s Sectional Maps of O‘ahu 1991

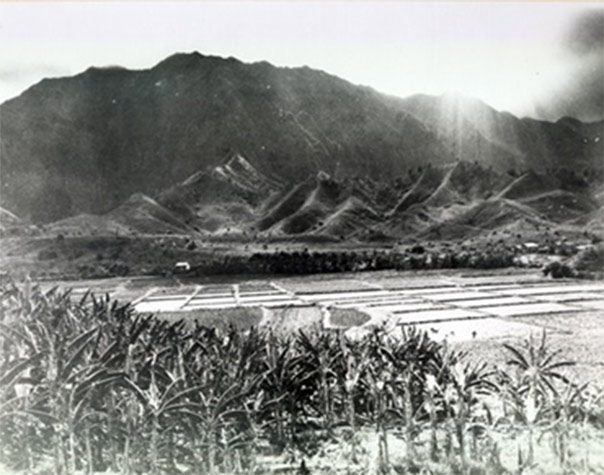

Hoi Wetland

Directly across the highway from He‘eia fishpond is a 400-acre wetland called Hoi (the large green area in Figure 2). The land was traditionally planted in taro patches (see Figure 6) and had four poi mills (Sanburn 2014). But this gave way to a succession of sugarcane, rice, and pineapple fields. After those plantations moved away, the land was used for cattle grazing, which explains the current abundance of California grass covering the wetland. The new land uses increased erosion and runoff during heavy rains, which degraded the health of He‘eia Fishpond.

Figure 6. Hoi Wetland, 1920s

Source: TenBruggencate n.d.

As mentioned above, in the 1970s the land was spared from housing and resort development by Kamehameha Schools. In 1991 Kamehameha Schools swapped this 405 acres of land for a much smaller piece of land in urban Honolulu from the Hawai‘i Community Development Authority (HCDA), a state agency. So, unlike the rest of the He‘eia watershed, this land is now owned by HCDA.

In 2010 HCDA granted a 38-year lease to Kāko‘o ‘Ōiwi, a community-based non-profit organization. Kāko‘o ‘Ōiwi was created in cooperation with the Koʻolaupoko Hawaiian Civic Club and is governed by a board of local residents and a Kūpuna Council (Council of Elders). Its main project is Māhuahua ‘Ai o Hoi (“Regrowing the Fruit of Hoi”), which aims to restore the agricultural as well as ecological productivity of the land, and transfer knowledge of traditional Hawaiian land stewardship practices and customs to a new generation. “This project is something the community has needed for more than 30 years,” said community activist Mahealani Cypher (TenBruggencate n.d.). The plan is to restore 220 acres of taro patches and use the remaining 185 acres for growing other foods (Villanueva 2015). At 30,000 pounds per acre, even just 75 acres would produce over 2 million pounds of taro (Kanekoa Kukea-Shultz, interview 9/23/14). “The plan is to put poi on the table for everybody,” according to board member Alice Hewett (TenBruggencate n.d.).

It is an organic farm; no herbicides are used to clear the land and the fertilizer is all organic matter, including algae from He‘eia Fishpond. So far 5 acres have been cleared and 3 acres have been planted to taro and vegetables. Breadfruit and banana trees grow along the fenceline. There are freshwater fishponds as well (loko i‘a kalo, Type IV in Figure 1). They previously held catfish and tilapia, but are now home to the native species āholehole (mountain bass) and ʻama‘ama (mullet). They are fed taro, pumpkin, sweet potato, and a high-protein meal such as soy (Kanekoa Kukea-Shultz, interview 9/23/14).

Figure 7. An endangered ae‘o flies over a taro patch at Hoi Wetland

Photo: Zach Villanueva, Office of Hawaiian Affairs

Kanekoa Kukea-Shultz is the executive director of Kāko‘o ‘Ōiwi and spends most of his time on the farm. He is also the Kāne‘ohe Bay Marine Coordinator for The Nature Conservancy of Hawai‘i. The farm fits in well with The Nature Conservancy’s efforts to restore the reefs of Kāne‘ohe Bay. Making the taro patch walls a little higher than usual greatly increases the water retention capacity—an estimated 280,000 gallons per rain event—which is crucial for reducing the sediment reaching the bay. The sediment not only smothers the reef, but also provides nutrients for the invasive algae that are smothering the reef. The farm also serves the Nature Conservancy’s goal of reviving endangered waterfowl: the ae‘o (Hawaiian stilt) has already made a comeback.

Currently the farm has four staff members. Unlike Paepae o He‘eia, Kāko‘o ‘Ōiwi does not receive any support from Kamehameha Schools. The Nature Conservancy pays Kukea-Shultz’s salary, and provides additional manpower in the form of Marine Fellows (Villanueva 2015). In the past, grants have come from the Office of Hawaiian Affairs and the Hawai‘i Community Foundation. Kukea-Shultz spends much of his time on grant writing. He must also contend with a cumbersome permitting process: although Māhuahua ‘Ai o Hoi is designed to restore the ecosystem, an environmental assessment is required as well as a Clean Water Act Section 404 Permit, a Special Management Area Use Permit, and a Conservation District Use Permit, among others (Kāko‘o ‘Ōiwi 2010).

Kāko‘o ‘Ōiwi sells taro directly to consumers around the island at $2.50 per pound and sells vegetables to local restaurants. It is hoped that over time the farm will generate more of its own revenue stream through the sale of its products.

Community work days are on the second Saturday of each month. I joined in on November 8, 2014. It was like working in a giant mud puddle. The crops grew in raised beds, but all around was 1-2 inches of water and very sticky mud. We did not begin with introductions, but by listening carefully as we worked, I found out the volunteers included: residents of the local community (including four children), a group of students from Hawai‘i Pacific University, some U.S. Vets, someone from Conservation International, someone from NOAA, two people from the restaurant industry, a Ph.D. student in Hawaiian Studies doing research for her dissertation, and the four Kāko‘o ‘Ōiwi staff members plus Kukea-Shultz. In all it was 40-50 people. We were divided into three teams: weeding, mulching, and staking. I chose weeding and spent about three hours weeding around chick peas, beans, carrots, peppers, tomatillos, and leeks.

Waipao

In 1999 long-time friends Rick Barboza and Kapaliku Schirman started a native Hawaiian plant nursery called Hui Kū Maoli Ola. They were concerned that

Centuries of severe habitat destruction and the introduction of countless exotic plants and animals have left Hawaii’s natural environment in a state of despair, with innumerable native plant species pushed to the brink of extinction (or over it!) and largely forgotten by the general public. (hawaiiannativeplants.com)

With little competition in the native plants market and growing public awareness of invasive species, plus an arrangement with Home Depot, Hui Kū Maoli Ola flourished. Barboza and Schirman expanded into habitat restoration, with funding from the federal government. They are now recognized as experts on native Hawaiian plants, as well as cultural and environmental experts. In 2005 Hui Kū Maoli Ola moved from Waimānalo to He‘eia, far up in the valley in an area known as Waipao. Landscaping was added to the business (Rick Barboza, interview 9/19/14).

Figure 8. Hui Kū Maoli Ola native plant nursery

Source: hawaiiannativeplants.com

When Hui Kū Maoli Ola opened its nursery to schoolchildren, the demand was so overwhelming that they decided to create a sister educational nonprofit organization, Papahana Kuaola, on an adjacent piece of land. That land had been an unofficial dump site for many years. It was full of construction debris, abandoned vehicles, etc. that all had to be cleared out (Rick Barboza, interview 9/19/14). Today it is clean and green, with a large house for offices and meeting space, a rock platform, and many gardens, including taro patches. Thanks to reforestation and stream restoration efforts, He‘eia Stream flows through strong and clear. Kamehameha Schools is the landowner and a key sponsor.

Papahana Kuaola’s education program seeks to address modern issues through Hawaiian knowledge. Education director Kīhei Nahale-a notes that modern academic systems are not created to sustain communities, and are not fulfilling to the students. It is crucial to reconnect the people with the land. Nahale-a teaches restoration and sustainability through tradition, creating skillsets and mindsets that honor the connection between people, land, and gods. Rather than merely education, he says, it is a “lifestyle practitionship” (Kīhei Nahale-a, interview 9/19/14).

Once a week, students from Hakipu‘u Learning Center work in the taro patch for physical education credit.

Papahana Kuaola programs that groups of all ages can choose from include:

- Aloha ‘Āina: Building relationship with ‘āina (land) through restoration work

- Nā Pana o Waipao: Cultivating a sense of place through storytelling and holoholo (walking)

- E ulu mau ka Hāloa: Strengthening identity through work in the lo‘i (taro patch) and with Hāloa (taro)

- E mālama i kou waiwai : Nurturing values through learning about waiwai (the water cycle) (papahanakuaola.com)

Besides field trips, there are after-school programs three days a week. Classes are also offered off-site, including on the island of Molokaʻi.

Like at Paepae o He‘eia, students provide revenue (about $6 per person) and a volunteer labor force as well. They work in the gardens and taro patches; in the forest they help weed out invasive species and plant native ones. The reforestation and riparian efforts reduce erosion, which in turn improves the quality of He‘eia Stream. The restored ecosystem benefits not just plants, but also birds, insects, and fish (Leong 2013).

Figure 9. 7th graders from ‘Iolani School at Papahana Kualoa

Source: iolani.org

Figure 10. Students from Kamehameha School catch invasive species of fish

Source: kuliablog.com

Community work days are the fourth Saturday of every month. Often large corporate groups participate, for example 200 Hawaiian Electric Company employees came in June 2013. Their tasks were to prepare a garden for rare banana trees; prepare guava wood and pili grass for a new structure; clean the taro patch; and plant native plants (HECO 2013).

On every third Saturday, Papahana Kuaola hosts the He‘eia Stream Restoration project. Between 2010 and 2014 this was a partnership between Hui o Ko‘olaupoko, Papahana Kuaola, Hui Kū Maoli Ola, and Ke Kula o Samuel M. Kamakau (charter school) with project funding from the Environmental Protection Agency and Hawai‘i Department of Health. The main goal was to restore native vegetation along the streambanks. Hui o Ko‘olaupoko has moved its stream restoration work to the other end of He‘eia Stream, clearing mangrove from the estuary near the fishpond, but Papahana Kuaola and Hui Kū Maoli Ola continue the upstream work. Hui o Ko‘olaupoko also works to inform the watershed residents about the importance of reducing fertilizer use, because nitrates and phosphates are high in the stream.

In addition, Papahana Kuaola hosts occasional evening programs, “Ho‘ale‘ale Kapuna,” a cultural series featuring teachings from the elders.

In all, over 20,000 people visit Papahana Kuaola each year.

Even further uphill, the Coast Guard communication station shown in Figure 5 was closed in September 1997. The land belongs to the Department of Hawaiian Homelands, and plans are underway to create the Hā‘iku Valley Cultural Preserve. The Ko‘olaupoko Hawaiian Civic Club has already been hosting work days and educational sessions at Kahekili Heiau (temple). Other important cultural sites in the area include Kaualehu Cave and Kane ame Kanaloa Heiau. They were used for burials. The Samuel Kamakau charter school is also in the area. The abandoned Coast Guard building might be converted to a museum. Besides cultural preservation and education, plans include repopulation with native vegetation. The Office of Hawaiian Affairs awarded a grant for work on the project to Ko‘olau Foundation (O’Connor 2011, various testimony on Senate Bill 2524, February 2012).

1 Within the watershed residents filed claims for smaller pieces (kuleana lands) and some families have lived on these lands for generations.

References

Apple, Russell A. and William K. Kikuchi. 1975. Ancient Hawaii shore zone fishponds: an evaluation of survivors for historical preservation. Honolulu: National Park Service.

Brooks, Mark. 1991. He‘eia Fishpond. Pp. 20-24 in Wyban, Carol A. (ed.) Proceedings of The Governor’s Moloka‘i Fishpond Restoration Workshop. Honolulu: Office of Hawaiian Affairs.

DHM Inc. 1989. Hawaiian Fishpond Study: Islands of O‘ahu, Moloka‘i and Hawai‘i. Honolulu: Bishop Museum.

DHM Inc. 1990. Hawaiian Fishpond Study: Islands of Hawai‘i, Maui, Lana‘i and Kaua‘i. Honolulu: Bishop Museum.

Farber, Joseph M. 1997. Ancient Hawaiian Fishponds: Can Restoration Succeed on Moloka‘i? Encinitas, CA: Neptune House.

HECO (Hawaiian Electric Company). 2013. Nearly 200 Hawaiian Electric volunteers learn about Hawaiian culture while helping to preserve it. Press release. http://www.hawaiianelectric.com/heco/_hidden_Hidden/CorpComm/Nearly-200-Hawaiian-Electric-volunteers-learn-about-Hawaiian-culture-while-helping-to-preserve-it?cpsextcurrchannel=1

Henry, Lehman L. (“Bud”). 1993. He‘eia Fishpond: An interpretive guide for the He‘eia State Park visitor. Kane‘ohe: Friends of He‘eia State Park.

Kako‘o ‘Oiwi. 2010. Mahuahua ‘Ai o Hoi Strategic Plan 2010-2015.

Keala, Graydon “Buddy” with James R. Hollyer and Luisa Catro. 2007. Loko I‘a: A Manual on Hawaiian Fishpond Restoration and Management. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources.

Kelly, Marion. 1975. Loko I‘a O He‘eia: Heeia Fishpond. Honolulu: Bishop Museum.

Kittinger, Jack. 2013. Our Modern Ahupuaʻa: Sustainable solutions for our communities. Green Magazine 5(1), p. 40-46.

Koani Foundation. 2014. Hawai‘i’s Ancient Fishponds – A Visit with Hi‘ilei Kawelo. Video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6MC_7BbmEUo

Leong, Lavonne. 2013. From the Mountain to the Sea: Saving the Heeia Ahupuaa. Honolulu Magazine, June 18. http://www.honolulumagazine.com/Honolulu-Magazine/June-2013/From-the-Mountain-to-the-Sea-Saving-the-Heeia-Ahupuaa/

Mishina, Christy. 2014. Culminating Paper: Eco Tipping Points: Maximizing Eco-Social Leverage Points. Prescott College.

O’Connor, Christina. 2011. Haiku Preservation Plan Wins OHA Grant. MidWeek, May 18. http://archives.midweek.com/content/zones/windward_news_article/haiku_preservation_plan_wins_oha_grant/

Office of State Planning, State of Hawai‘i. 1992. Kane‘ohe Bay Master Plan.

Sanburn, Curt. 2014. The Flowing Lands: Restoring O‘ahu’s Ahupua‘a. Hana Hou 17(4), p. 80-91.

TenBruggencate, Jan. n.d. 'Taropy': Healing an Ahupua‘a. The Nature Conservancy. http://www.nature.org/ourinitiatives/regions/northamerica/unitedstates/hawaii/explore/the-nature-conservancy-in-hawaii-taropy.xml

Villanueva, Zach. 2015. In He‘eia ahupua‘a, an OHA grantee makes strides in land sustainability. Ka Wai Ola 32(6), p. 13.

Wyban, Carol A. 1991. Lokoea Fishpond. Pp. 12-19 in Wyban, Carol A. (ed.) Proceedings of The Governor’s Moloka‘i Fishpond Restoration Workshop. Honolulu: Office of Hawaiian Affairs.

Appendix: EcoTipping Points Analysis by Kamehameha School Students

Courtesy of Christy Mishina

Assignment

- First think about everything you have learned about the Eco Tipping Points success stories and their ‘Ingredients for Success’. You have seen several examples of successful tipping points stories and we have discussed why they were successful.

- Next, consider all that you have learned about the background, history, and current state of He‘eia Fishpond along with its negative and positive tipping factors. You have learned about fishponds in general as well as specific information about He‘eia fishpond.

- Now, taking all of that information into account, write a reflective essay explaining whether or not you believe He‘eia Fishpond is an example of a successful Eco Tipping Points story. Please use evidence from the website, the keynote, the videos, class discussions, your worksheets, your first hand experiences, etc. to back up your stance.

- When you have completed your essay, compare it to the grading rubric, revise and edit as necessary. There is no correct answer, so you will be graded on how complete your ideas are communicated and how well you back up your ideas with supporting evidence.

He’eia Loko I’a Essay

T. Cox

I am surprised at what the Hawaiians of old were able to build and accomplish. They did not have heavy machinery or equipment but with their understanding of the land and the sea, they successfully built some of the best aqua cultural fishponds in the world. After visiting He’eia Loko I’a I am both sad at the current condition of He’eia and yet proud to be able to identify myself with the Hawaiian culture.

I learned Princess Bernice Pauahi’s father, High Chief Abner Paki received the lands of He’eia at the time of the Great Mahele of 1948. After Princess Pauahi’s father and mother, High Chiefess Laura Konia, died, she was given the lands of He’eia. After the Princess died, her husband, Charles Reed Bishop took care of all of her lands in the Bishop Estate. Today, Kamehameha Schools owns He’eia Loko I’a.

He’eia Fishpond is a kuapā or walled type of fishpond. The kuapā is about 7,000 feet long and 12-‐15 feet wide and forms a circle around the pond. He’eia has six mākāhā or sluice gates – three along the seaward edge to control the salt water input and three along the He’eia stream to control the fresh water input. When salt water and fresh water mix, it is called brackish water. Some of the plants and animals that live in He’eia are limu, moi, papio, aholehole, puhi and pipi.

As the years passed, there was land development near He’eia and then the Keapuka Flood of 1965 destroyed a 200 foot section of the kuapā. For about 25 years no one used the fishpond and in 1988 Mark Brooks and many volunteers fixed the broken section of the wall. In 1998, Mark Brooks and the University of Hawaii at Mānoa planted the seeds for the current restoration and Paepae o He’eia.

To bring He’eia back to a healthy and sustainable fishpond, I looked at the positive and the negative factors. After visiting He’eia, I realize and understand how important this fishpond is to me and my Hawaiian culture. I also realize how much work, time and dedication it takes to take care and restore He’eia.

The first positive factor for a sustainable He’eia was the mangrove removal. The mangrove was used to help control erosion but is spread to all parts of the fishpond and did more damage to the wall and rocks than good.

The second positive factor in the restoration of He’eia is Kū Hou Kuapā which means, “Let The Wall Rise Again.” The goal is to restore the ancient wall to preserve the integrity of the fishpond and support our unique culture, education, and aquaculture programs.

Third, Paepae o He’eia has been removing invasive limu. When the reef is clean and not covered with invasive limu it is healthy and strong. Paepae o He’eia has removed 50 tons of invasive limu by hand or net from 2004 to 2012. The limu is not thrown away in our landfills. Farmers use the limu as fertilizer.

With the removal of invasive limu, the reintroduction of native limu to He’eia is a positive eco tipping point.

There are the big projects like the wall restoration and there are the small jobs that all add up to restoring He’eia Fishpond. Another positive factor is the trash

pickup activities that are scheduled at He’eia.

The last positive eco tipping point is the upland restoration. When development and growth happens upland from the fishpond, pollution and run off helps to destroy the ecosystem in the fishpond. Lucky, now that the community and government are aware of this pollution, He’eia Fishpond shouldn’t suffer.

Whenever there is positive, there is usually negative and I believe He’eia Fishpond seen more than its share of negative eco tipping points. The first negative tipping point was the Great Mahele. What was supposed to keep Hawaiian lands in the hands of the Hawaiian people ended up making many of them lose their lands. The traditional land system changed to the concept of private ownership and in the end most of this land was sold or leased to foreigners.

Second, it was cheaper to import fish than it was to raise fish. When the cost to take care of the fishpond increased, and the amount of labor it required to raise fish in the fishpond increased, importing fish was cheaper and became the norm.

Third, as streams were diverted people didn’t realize what was going on downstream. When the route of a stream is changed it could affect many things in its path. At He’eia, stream diversion caused a lot of harm to the delicate chemistry of the fishpond.

Similarly, upland developments caused pollution is streams. It also caused run-offs. When the land around and near He’eia started to change and grow, this caused rain water run-‐off to enter the fishpond and streams and also causing pollution.

Another negative tipping point is when invasive species took over He’eia.

Invasive mangrove and limu are the two species that restoration groups are always battling. The mangrove blocks the sunlight and wind to He’eia. Blocked light prevents the growth of native limu that fish feed on. Blocked wind makes the water temperature warmer and warmer water hold less oxygen.

Finally, one of the biggest negative tipping points is the decrease of fishponds. Loko i’a was very important to the sustainability of the Hawaiian people. As the years went by, we saw less and less fishponds in use. It was because of the Great Mahele, the cost to maintain, pollution and invasive species that decreased the amount of active fishponds.

The only way to keep the loko i’a healthy and thriving with sea life is with hard work and dedication. There are ten ingredients for success:

1. Outside stimulation and facilitation – “An Eco Tipping point story typically begins when people or information from outside a community bring on a shared awareness about a problem.”

The Paepae o He’eia organization is committed to restoring and caring for the He’eia Fishpond. I believe it is organizations like Paepae o He’eia that help build community awareness about the importance of cultural sustainability. By sharing their knowledge about He’eia with others and organizing community volunteers to help remove invasive species and sediment in the pond, restore the wall around the pond, and trash pickup activities, they help people understand the importance of perpetuating our Hawaiian culture.

2. Strong democratic local institutions and enduring commitment of local leadership – “The community moves forward with its own decisions…everyone feels a sense of ownership.”

The community of He’eia consists of volunteers having a voice, commitment, and dedication to one goal – “to implement values and concepts from the model of a traditional fishpond to provide intellectual, physical, and spiritual sustenance for our community.” (paepaeoheeia.org) When everyone who cares for He’eia moves forward together, it creates a sustainable fishpond that feeds people fish and protein. “If you take care of the pond, the pond will take care of you.”

3. Coadaptation between social system and ecosystem – “Social system and ecosystem fit together, functioning as a sustainable whole. When one gains, so does the other.”

I learned when there is an understanding between the community and the eco system and they work together as one, both systems will be successful and healthy. The He’eia, Fishpond is not a working fishpond and is not operating correctly and this does not make a win-‐win-‐win situation. However, I believe that when the community restores He’eia Loko I’a and it provides fish and protein to eat, coadaptation between the social system and ecosystem has been achieved and we will have a win-‐win-‐win model.

4. Letting nature do the work – “Eco Tipping Points create the condition for an ecosystem to restore itself by drawing on nature’s healing powers.”

Although He’eia needs plenty of help from people and the community, nature offers plenty of help. With the wall still broken and the takeover of invasive species, the fishpond is unable to function and pursue its purpose of providing a source of sustainability. Once the wall is restored and the invasive species controlled, we will begin to see “nature’s healing powers.” Sediment levels will slowly disappear, creating healthier water, native plants will regrow and populate naturally, and the fish will have a healthier diet.

5. Rapid Results – “Quick “payback” and something that can stand as a symbol of success help communities stay committed to change.”

When the people and communities involved see the results of their hard work, they will stay dedicated. The newly built hale, rock wall and sluice gate at He’eia stand as symbols of everyone’s hard work, effort, cooperation and dedication.

6. A powerful Symbol – “Something that serves as inspiration or stands for success in a way that helps communities stay committed to change.”

There are many achievements and symbols at He’eia. For example, the break in the wall remains broken and I believe it symbolizes our Hawaiian culture. When it is fixed, the fishpond will be filled with fish and the He’eia people will continue with the Hawaiian culture and traditions of fish farming. Another powerful symbol is the 3,500 foot mark of the removal of mangrove.

7. Overcoming social obstacles – “Overcoming social, political, and economic obstacles that could block positive change.”

Another ingredient for success for He’eia Loko I’a is receiving a permit to re-‐build the wall after three years of fighting with the government.

8. Social & ecological diversity – “Diversity of people, ideas, experiences, & natural elements provide more choices & opportunities, with better chances that some of the choices will be good.”

Success is achieved when everyone join ideas and work together to reach one goal. There are a few organizations and many volunteers associated with He’eia. Although they each come from different age groups, experience levels, ethnicities and values, everyone works and laulima or cooperate with each other to reach the same goal – “to perpetuate a foundation of cultural sustainability for communities (‘ohana) of Hawai`i through education.” (paepaeoheeia.org)

9. Social and ecological memory – “Learning from the past adds to the diversity and often points to choices that were once sustainable. Nature has some of this memory built in.”

He’eia’s sustainable past adds diversity to the present because we could have a natural and sustainable fishpond resource that we learned from our knowledgeable kūpuna.

10. Building resilience – “Locking in” sustainability by creating the ability to adapt and deal with new (and often unexpected) conditions that threaten sustainability.”

When we can adjust to new and unexpected conditions, I believe we can achieve sustainability. Paepae o He’eia’s hands on approach allows us to experience our Hawaiian culture and traditions through a sustainable resource. While learning and sharing the ancient and sacred ways of sustainability they are perpetuating and educating us on our Hawaiian culture and heritage.

I believe He’eia Fishpond is a good example of a successful Eco Tipping Points story. I believe it is a success because of the community group like Paepae o He’eia and schools like Kamehameha Schools that continue to educate students and people about the importance of restoration and sustainability. By experiencing He’eia first hand, I can understand how hard the work was to raise your own food. Every day I take things for granted. When I’m hungry I open a bag of chips. When I’m thirsty, I open a bottle of water. Our fieldtrip to He’eia made me stop to think how lucky I am. It also made me understand the importance of learning how my ancestors lived. They didn’t need power machines, computers or smart phones but they were very akamai and successful.

He‘eia Essay

H. Dikilato

There have been many instances throughout the history of the world where a bad situation was transformed into something better. These stories include eco tipping points as well as ingredients to success. He‘eia fishpond was once a thriving resource that provided for the community. After years of neglect, this great fishpond began to fall apart. How could we restore this one thriving loko kuapa?

He‘eia was once a flourishing fishpond when our kūpuna were managing it. It was a great resource of food for the island of Oahu, until the negative tipping points affected this wonderful place. According to what we learned from the He‘eia keynote, the Great Mahele changed the original land ownership system, resulting in Hawaiians losing their lands. Changes in economy also drove the kanaka towards the city in order to gain money, resulting in leaving their lands behind. After these unfortunate events, imported fish became normal due to lower costs and less labor, allowing the fishpond problems to spiral even further down.As upland development began and He‘eia was left unmaintained, more problems occurred. Streams were diverted and the development on land contributed to runoff and pollution to streams that feed into the fishpond. The massive harvesting of trees also led to runoff that ended up as sediment in the pond. Lastly, invasive species, such as mangrove, began to choke the fishpond, not allowing native limu growth and trapping sediment in the pond. Invasive limu began to grow and took over the pond, adding to large amount of negative tipping points.

Although there seemed to be little hope in restoring Heʻeia fishpond, an outside stimulation called Paepae o He‘eia came to restore this once flourishing kūapa. In class, we learned that Paepae o He‘eia began to remove the massive amounts of mangrove the resided in the pond, allowing the water to flow. From our experience at the pond, we found out that these mangrove trees were later used for wood to make a hale, which meant that the people were able to take something bad and turn it into something good. Paepae o He‘eia are starting to rebuild the kūapa and also began clearing out invasive limu that has infested the pond. In the future, they will remove sediment and restore the uplands. In class, we learn that once the aina is restored and the mangrove is gone, the sediment will be naturally flushed out of the pond and the native species will come back on their own. This is an excellent example of “letting nature do the work”, due to the fact that nature is restoring itself because of the eco tipping points.

All of the work at He‘eia couldn’t have been made possible if it wasn’t for Paepae o He‘eia and their volunteer opportunities. Through the He‘eia website, we learned that people outside of Paepae o He‘eia helped them to restore the fishpond. They were able to involve the Hawaiian community with the project and allowed the kanaka to feel a sense of ownership. This is an example of strong democratic institution and enduring commitment of local leadership. Having volunteers working at He‘eia also promotes social and ecological diversity. Since there are so many people who come from all walks of life that with the restoration, they have a variety of men and women who contribute different ideas, experiences, etc.

He‘eia’s journey from being a forgotten loko kuapa to an almost operational fishpond took hard work and included many ingredients to success. For instance, if we take care of the fishpond, the fishpond takes care of us due to the fact that it teaches us about of culture and allows us to learn about our kūpuna. This creates a win-‐win-‐win situation and a coadaptation between social system and ecosystem. The land wins because we’re cleaning it up, the people win by learning about their culture, and I win because of the mana‘o that we’re being taught.

He‘eia fishpond also had some obstacles that stood in their way. For example, in class, we learned that many years ago a portion of the kuapa was knocked down in a storm. Paepae o He‘eia tried to restore the wall but couldn’t get a wall-‐building permit. After years and years of never giving up and pushing to get the permit, they finally received permission, thus overcoming a social obstacle. This event could have also been seen as a powerful symbol because it served as inspiration and stands for success. From our first hand experience at the fishpond, we also learned that they cleared 3,500 feet of mangrove, which is another inspirational event that shows that their work can make a difference.

In my opinion, I don’t think that He‘eia had any rapid results. All of their accomplishments like clearing the mangrove and getting the wall-‐building permit took years and years to do. From reading their website, we learned that Paepae o He‘eia was created in 2001 and has been working non-‐stop on the loko kuapa since then. They have done so much to restore the fishpond, but the results didn’t come quickly. They have been removing mangrove for years and there is still a lot to be removed. It has been a long work in progress, which is why I don’t believe that there has been any quick “payback”. As a result, I don’t think that there have been any rapid results in the restoration of the fishpond.

With all of these good and bad tipping points, He‘eia is beginning to be the fishpond our kūpuna used to fish out of. The pond is still a work in progress, but Paepae o He‘eia is doing a great job at restoring this piece of history. We are trying to learn from what worked before in order to make this fishpond work, thus promoting social and ecological memory. From the fishpond website, we learned that Paepae of He‘eia brings in students from multiple schools from around the island. Through this, the next generation is learning about the loko i‘a and the knowledge is being passed down to them. Through building resilience, we hope that He‘eia’s legacy will live on for generations to come.

He‘eia Fishpond

K. Liu

Here is a journey of a loko kuapā called He‘eia Loko I‘a. This one fishpond has gone through so much, but when the time of The (not so) Great Mahele came thats when it all went down hill. In the time of The (not so) Great Mahele which was 1848 the native Hawaiians ahupua‘a system was broken. According to the keynote and script made by Ms. Mishina, The (not so) Great Mahele started private ownership of the land and denied people access to resources that were once shared. What followed after The (not so) Great Mahele (also found on keynote) was the changing of the economy. The economy changed from a subsistence economy to a market economy. The changes in the economy led to the breakdown of roles and responsibilities. Therefore many had to leave the land for towns to make money for their families. After all that happening the Hawaiians connection and relationship to the land was changed. 30% of the Hawaiian population recieved land awards during the time of The (not so) Great Mahele, 70% of the population were left landless which meant loss of land to loss of family. There was a great decline of operating fishponds (information from script). There were about 350 in use in 1800 but in 1900 there were 158 and finally in 1994 there were 122 classified as being in fair excellent condition. I was taught by a man of Paepae O He‘eia that lower cost and less labor requirements led to the importing of fish . Streams were diverted and the diverting of streams messed up the chemistry of fishponds. According to the photos seen in the keynote pollution came from upland development as well as the harvesting of trees and grazing animals . These polluted streams led to the fishpond with soil run-‐off that ended up as sediment. There was a flood called the Keapuka Flood which happened in 1965. This flood destroyed 200+ feet of the kuapā. As I have seen with first hand experience the introduction of an invasive plant called mangrove huge problem that still continues. The mangrove blocked light which prevented the native limu to grow, blocked the wind which caused the pond water to become warmer meaning there was less oxygen in the water and it retained sediment that soon flushed out into the pond. Acanthophora spicifera and gracilaria salicornia are two names of invasive limu that took over the fish pond and prevented the native limu to grow. These are the many negative eco tipping points of He‘eia Loko I‘a.

A non-‐profit organization called Paepae O He‘eia was established in 2001 and is a group of young hawaiians who have come and partnered with the land owner Kamehameha Schools (our school) to save this fishpond that was once and still is a huge part of our culture and history. According to the website paepaeoheeia.org they have 6 steps to returning this fishpond back to a healthy state. They are mangrove removal, kuapā rehabilitation, invasive limu removal, sediment removal, native limu restoration and upland restoration. As I have seen at the fishpond half of the mangrove around the pond has already been removed. Paepae O He‘eia is also helping to build a house to with the mangrove because the previous house was burnt down with the mangrove we debarked on our field trip to He‘eia Fishpond. Paepae O He‘eia has finally gotten their permit to fix the remaining part of the wall that needs to be rebuilt due to the Keapuka Flood.

The outside stimulation and facilitation came from UH creating a class to teach there and then from that came along the non-‐profit organization Paepae O He‘eia. These are the groups that brought information and shared awarness about the problem in this fishpond. I believe that they have strong democratic local instutuions and enduring commitment of local leadership because everyone who helps restore the fishpond such as Paepae O Heʻeia and volunteers feel ownership of this fishpond. But they could do better and persuade others to get involved starting with the people who live in the ahupua‘a and eventually they could persuade the whole island perhaps. This fishpond does have a coadaptation between social system and ecosystem “win-‐win situation” because we take care of the pond and the pond takes care of us by feeding us fish and teaching us more about our ancestors and culture. With this fishpond is originally and is mostly “letting nature do the work” because the fish reproduce themselves, the tides still come and go flushing out the sediment and bringing in fish, the native plants are starting to come back on their own and the food for the fish is naturally in the fishpond. One of the rapid results of this fishpond is that they are still able to harvest/ produce fish. I got this information from the video of them harvesting fish on paepaeoheeia.org. The powerful symbols of this fishpond I learned from the people of Paepae O He‘eia are ½ (3,500 feet) of the mangrove removed, permit to build the part of the wall that was destroyed,the harvesting of the fish and the healthy relationship between the fishpond and the community/ hawaiians. Some overcoming social obstacles are the state wouldn’t approve the permit of Paepae O He‘eia finishing the kuapā but finally after fighting for it for so long they finally got it. The other obstacle is the community/ neighborhood complaints form people who own houses and live there. An example of social and ecological diversity is the many different types of people who work at He‘eia Fishpond and volunteer there. They differ in age, ethnicity and values. He‘eia Loko I‘a has social and ecological diversity because Paepae O He‘eia is using the ways of our ancestors to create a sustainable fishpond like once before, they are bringing it back. The people of the fishpond are building resilience by teaching others and “locking in” the information to the younger and new generations. I know this because I was one of many who were able to learn about this fishpond and how to care for it.

A loko kuapā is a royal fishpond surrounded by a wall made of stone and where men caught the fish. The first recorded owner of this fish pond is High Cheif Abner Paki who is the father of the founder of our school, Princess Bernice Pauahi Bishop. Our ancestors were very intellegient they knew that by creating a brackish water pond with lots of food for baby fish, the baby fish would come in through the small entrances in the gate, they would then eat to much and be too fat to fit out of the gate to go out to the salt water. The fish were then harvested and some were set free to reproduce to balance the population of the fish. The two fish harvested there are ‘ama‘ama (mullet) and ‘awa (milkfish). The non-‐profit organization called Paepae O He‘eia is a great organization they help teach the new, next or younger generations how to keep the fishpond safe and to keep it from pollution. The have done lots of things to help the health of the fishponds as stated before. I was given the privledge to get to meet the people of this organization they are very hard working people, I give them credit for for all that they have done, it truely is amazing. I got to experience debarking mangrove and passing logs of mangrove. I appreciate all they have done for this fishpond.

I believe this a good example of a sucessful eco-‐tipping point story because from all that this fishpond has gone through since 1848 the volunteers, Paepae O Heʻeia and the community has done an outstanding job getting the fishpond in the state it is in now is amazing. I thank them for all they have done. This is a fishpond that has had a long journey and is still standing as strong as it can.

He‘eia Loko i‘a

M. Melim

Over the years, many people and organizations have tried to restore He‘eia Fishpond back to how it was in ancient times: thriving and beautiful, providing food and sustainability for the people of the land. But even with all of the hands that have put so much time and effort into helping this cause, He‘eia Fishpond still doesn’t seem like a successful Eco Tipping Point Story to me.

As time passed, He‘eia Loko I‘a has faced many negative factors that caused them to tip the wrong way. The first factor that set off this chain of events was The (not so) Great Mahele. During this period, many people were separated from their land so they were unable to mālama it. The slideshow that we saw about loko i‘a stated that only 30% of the Hawaiian population received land, causing the subsistence economy to become a market economy and that changed the view of the ‘āina as just something they could make money off of. Two other factors that had a big impact on the fishpond was the Decline of loko i‘a and storm that damaged the kuapā. From the 1800s to the mid 1190s the amount of functional loko i‘a went from about 350-122. To make matters worse, a storm in 1965 wiped out a section of the rock wall, leaving a gap in one of the most crucial parts of the fishpond. Polluted water from upland development, sediment caused by grazing animals and the harvesting of erosion control trees, and streams being diverted for other purposes are just some of the more recent negative factors that have added to the fire.

Though it may seem like the condition of He‘eia fishpond is still traveling downhill, there are many things signaling that tipping into the positive zone could be just around the corner. On the Paepae o He‘eia website, I noticed three programs (or factors) that are helping to rebuild the fishpond: Kū Hou Kuapā~Restoration of the Kuapā, Ka ‘Ai Kamaha‘o~Educating the people about the loko i‘a and how to care for it, and ‘āina Momona~Production of the different things that the loko i‘a provides. But, none of these things could be put into action if they didn’t have all of their volunteers that kokua. Some of the things that the volunteers do to help restore the pond are removing mangrove and invasive limu and gathering rocks to finish the damaged section of the kuapā. Aside from all the hard work and labor, I think that another positive factor is that they are able to produce things from the loko i‘a. Not only can they catch fish, crabs and oysters for themselves, but they share it with the people of the community. Taking in the ways of our ancestors, they use every resource that they have, just like how we debarked mangrove for the new hale at Ka‘ala farms.

An Eco Tipping Points story couldn’t be successful unless it had all the Ingredients for Success. The ingredients that I believe that He‘eia loko i‘a already has are Outside Stimulation and Facilitation, Letting Nature do the Work, A powerful symbol, Overcoming social obstacles, Social and Ecological diversity, Social and Ecological Memory and Building Resilience. The Outside Stimulation and Facilitation that I recognized was Paepae o He‘eia. Though there were different owners and stewards of this fishpond, they were the ones to make the most positive difference. We can’t truly destroy nature, so when I see the ingredient Letting Nature do the Work, I think about how the tides bring the fish in through the mākāhā and how removing the mangrove helps to circulate the sediment so that the native species can grow back. One of the Powerful Symbols and an example of Overcoming Social obstacles for He‘eia loko i‘a is when they were finally able to get their permit to rebuild the kuapā. Some proof that they have Social and Ecological diversity is the people who volunteer are of all ages, sizes and races. They even work with schools, other organizations and share their methods of restoration with different fishponds. The Social and Ecological memory comes from all of the knowledge, practices and methods that our kupuna passed on to us and the way it is integrated with the Western ways of thinking. I think the most important ingredient is Building Resilience. Paepae o He‘eia is educating the people-especially the children-about the fishpond so that we can ensure that the future generations have a fully sustainable loko i‘a.

The ingredients that I feel can’t be identified with a yes or no are: Strong democratic local institutions and enduring commitment of local leadership, Coadaptation between social system and ecosystem and Rapid Results. For the Strong democratic local institutions and enduring commitment of local leadership ingredient, I think it all depends on how you define “community”. Community to one person could mean the people who live in that area. Community to another person could mean the people who take care of the fishpond. In this case, I’m thinking of the Hawaiian community. The ups and downs of He‘eia fishpond don’t effect all of the Hawaiian people and not everyone has helped this cause. The Coadaptation between social system and ecosystem is partially shown. The fishpond is not fully self-sufficient because of things like the mangrove and the hole in the kuapā, but they are still able to produce things from it. When I see “Rapid Results” I think about instant change. But, since many things that Paepae o He‘eia does to make a difference takes time, seeing even a little bit of progress can take a while.

To some, it might seem impossible that the loko i‘a will ever be restored to its full potential because of all the problems that it has and new ones that might arise. But, I think that if a few more positive ingredients are added to the mix, we can experience He‘eia Loko i‘a as our kupuna did. “He ali‘i ka ‘āina; he kauā ke kanaka.~The land is a chief; man is its servant.” Our ancestors believed that it is our kuleana to mālama the ‘āina. If we all help to make others more aware of these kinds of problems in our own home, then maybe one day all of our Eco Tipping Point stories will be successful, and we can reverse the thinking that land is an object, not something to be treated with aloha and care.

Citation

http://www.nakilohonuaoheeia.org/site-description/

He‘eia Fishpond- Nā Kilo Honua o He‘eia

http://paepaeoheeia.org

Paepae o He‘eia

http://ksdl2.ksbe.edu/heeia

Virtual Field Trip to He‘eia Fishpond

http://www.kumukahi.org/units/ka_honua/ao/aina

Kumukahi

He’eia Loko I‘a

M. Moody

He‘eia Loko I‘a is a valued place in Hawai‘i where everyone that belongs to the Hawaiian heritage would want to save it and keep it going on forever. This was a place where the ancient Hawaiians would gather their food after a long, hard day of working in the loʻi. They had worked so hard to make sure that this system that they had thought of worked and could support them for the future generations. But when a tragic event happened (Keapuka flood) in 1965, most of their hard work was banished by the heavy ua that struck the handcrafted wall that had protected their food. Ever since then, communities and organizations have been trying to get this fishpond back together again so we can use this resource to help us live like our ancestors and connect to them as well.

This fishpond has gone through many ups and downs throughout the last 50-‐60 years that have made fixing this fishpond even harder for the people of Hawai‘i. For example, the Great Mahele started the idea of private ownership and abolished the traditional land system, so this separated the people of Hawai‘i from working together as a community to help contain the fishpond so it could stay healthy. Loss of land started to occur after the Great Mahele was made, people would no longer have the land that would help them in survive because it would now belong to the higher seated chiefs and Hawaiians. And not shortly after that, the storm in 1965 had destroyed the rock wall. This set back the Hawaiians from actively using this on a regular basis and this also meant that they would have to rebuild the fishpond if they ever wanted to use it again. While the wall started to fall apart, so did other parts of the fishpond. The mangrove, sandalwood, and iliahi plants/trees started to take over the fishpond, slowly choking it to its final death. The mangroves started to make shade and block the wind from cooling the water, so this would make the water warmer and kill the fish and plants living in the fishpond, one by one. The sandalwood and iliahi started to grow in the fishpond and infested the land around it also. And since the rock wall had broke during the big storm, the fish living in the fishpond started to escape through the big hole formed from that one night. People were starting to care less about the pollution they made in the streams flowing through the land, so since the people were growing more trees in the uplands, the pollution being made from them was started to crowd up the streams, flow down to the fishpond, and pollute it. Pollution was also coming from the upland development, and they flow down and pollute the streams. The labor requirements started to become less and less, and the costs of items started to lower as well. And from that, imported fish products became a pattern with the Hawaiians. They had to do this because they could not supply themselves with their own fish cause the fishpond could no longer support them and help them live like the way it used to be. But right when it looked like the Hawaiians had lost in their fishpond, things started to go uphill from there. Communities started to work together to remove the mangrove and invasive limu that has been harming their fishponds. And after they completed that task, they introduced the native limu back into the fishpond, so the fishpond would contain healthy, native plants. Instead of unhealthy, invasive plants that would kill the fishpond all over again.