EcoTipping Points

- How do they work?

- Leveraging vicious

cycles to virtuous - Ingredients for success

- Create your own

EcoTipping Points!

Stories by Region

- USA-Canada

- Latin America

- Europe

- Middle East

- South Asia

- Southeast Asia

- East Asia

- Africa

- Oceania-Australia

Stories by Topic

- Agriculture

- Business

- Education

- Energy

- Fisheries

- Forests

- Public Health

- Urban Ecosystems

- Water and Watersheds

Short Videos

- Saving a Coral Reef and Fishery (Apo Island, Philippines)

- Community Gardens Reverse Urban Decay (NYC, USA)

- Community Forests Reverse Tropical Deforestation (Thailand)

- Escaping the Pesticide Trap (India)

- Rainwater Harvesting and Groundwater Replenishment (Rajasthan, India)

How Success Works:

- Saving a Coral Reef and Fishery (Apo Island, Philippines)

- Community Gardens Reverse Urban Decay (NYC, USA)

- Community Forests Reverse Tropical Deforestation (Thailand)

- Escaping the Pesticide Trap (India)

- Rainwater Harvesting and Groundwater Replenishment (Rajasthan, India)

Human Ecology:

Principles underlying

EcoTipping Points

Water Warriors: Rainwater Harvesting to Replenish Underground Water (Rajasthan, India)

- Author: Amanda Suutari and Gerry Marten

- Posted: June 2005

- Site visit assistance and editorial contributions: Steve Brooks and Ann Marten

- Short video of this story (11 minutes)

- Educational materials: “How Success Works” lesson for this case (study plan, narratives of various lengths, photos, PowerPoints, student worksheets, teacher keys)

- This story features a Photogallery

Contents of this page

- The narrative (immediately below)

- Photos for the narrative

- Ingredients for success in this story

- Feedback analysis for this story (vicious cycles and virtuous cycles)

- The complete report on this story - “Restoring Rajasthan’s Traditional Earthen Dams for Rainwater Harvesting and Groundwater Replenishment” by Amanda Suutari

- An update on this story (January 2014) - “Learning from Tarun Bharat Sangh’s dissemination of rainwater harvesting in Rajasthan, India” by Ted Swagerty

- “Summary of a Tarun Bharat Sangh Report: FLOW – Impact of TBS Work on River Rejuvenation” by Regina Gregory

- “India’s National Water Community” by Ted Swagerty

- An update on this story (February 2014) - "KRAPAVIS: Sacred Forests and Rainwater Harvesting in Rajasthan, India" by Vikas Birhmaan

The wells in Rajasthan’s Alwar District had dried up, thrusting the people into abject and seemingly inescapable poverty. The revival of traditional earthen dams to capture rainwater for recharging the underground water supply provided a tipping point that brought the wells back to life. And with the water came a better life for the people. It started in the spare, humble village of Gopalpura. Nearly a thousand villages are now following Gopalpura’s example.

Rajasthan receives a scant 16 inches of rainfall annually. Most of it falls during the monsoon months from June to September, leaving the soil to parch the rest of the year. Religious rituals have emphasized how precious water is. “When a male child is born, or when a couple marries, the village has a ceremony where they walk around the well in worship of the water,” says Murali Lal Jangid, from the village of Jamdoli. “And when a person dies, the body is cremated, and the remaining bones are brought to a religious site where there is holy water. It shows how water is related to our culture from birth to death.”

Rajasthan has long been known for its underground water supply. Ancient Hindu scriptures mention the key technology: rainwater harvesting. Drawing upon centuries of experience, people built structures to catch and hold the monsoon rains and store them for the dry season to come. Archeologists have dated some rainwater catchments as far back as 1500 B.C. The dominant structure was the johad, a crescent-shaped dam of earth and rocks, built to intercept rainfall runoff. A johad served two functions. On the surface, it held water for livestock. But like an iceberg, its most important parts were below the surface. By holding water in place, it allowed the liquid to percolate down through the soil. It recharged the aquifer below, as far as a kilometer away. Stored underground, the water could not be lost to evaporation. In the midst of the dry season, without pipes or ditches to deliver water, villagers could always count on plenty of water from their wells, and irrigated fields lush with wheat, mustard and beans.

A johad was more than any one family could build. It took a village. But because every villager had a stake in the johads, residents banded together to build and maintain them. The rajas, the kings of small states who gave the region its name, would often finance johad construction, taking a sixth of the crops in return. Community institutions extended to other shared resources. Because forest conservation was bound up with water, villagers regulated the cutting of trees. As late as 1890, 60 percent of the land was covered with forests where villagers gathered firewood and royal families went hunting for tigers.

Nor Any Drop to Drink

After centuries of relative stability, the social contract around water and trees began to fall apart when Great Britain consolidated its control over India late in the 19th century. Crown companies were hungry for timber, and too many princes were willing to provide it. First, they declared the forests off-limits to the villagers who had tended them for generations. Later on, they sold the logging rights. Rajasthan’s Alwar District kept its forests until the late 1940s, when India was heading toward independence. Then the local raja, afraid of losing his lands to the new national government, let the loggers in. The venerable trees turned into railroad ties and charcoal.

The deforestation of Alwar set off a slow-motion chain reaction in which the ruin of one resource led to the ruin of others, and the impoverishment of nature led to the impoverishment of the people. The first wave of degradation was the loss of the trees themselves. Their destruction starved out wildlife and exposed the topsoil to erosion. When the rains came, they washed soil down the treeless hillsides, and much of that soil was deposited in johad ponds. Over time, thousands of johads were filling with silt. As silted johad ponds channeled less water underground to recharge the aquifer, the underground water began to retreated deeper below the surface.

In earlier times, villagers would have dug out the silt and rebuilt their crumbling dams. But as the government seized more and more of their common lands, they had less and less incentive to protect what was left. Where farmers had once banded together to manage their resources, now they competed over the dwindling remains. Traditional village councils, called gram sabhas, fell apart, and a tradition of communal labor washed away with the topsoil. “After independence,” recalls Gopalpura village elder Mangu Patel, “village unity collapsed, and the people neglected their johad structures, because johads can only be made by a group, not by individuals. So, one by one, the structures gradually deteriorated and stopped being used.”

In place of johads, the villagers turned to modern technology to keep the water flowing. With government aid in the 1950s, they began drilling “tube wells”– deep wells that brought up the water with diesel-powered pumps. But the new wells ensnared them in a vicious cycle. When the water table dropped, they drilled even deeper; and the deeper they drilled, the more the water dropped.As a villager explained, “Everyone was very enthusiastic when a new tube well came to our village, because there was not much labor necessary to get the water. They just turned on the switch and got as much as they wanted. But they took so much water – they could take it 24 hours a day – and underground water levels dropped so much that eventually it became impossible to get water more than five or six hours a day.” Eventually, the underground water dropped deeper than people could drill, wells began to go dry, and even streams and rivers were drying up.

The advent of tube wells and the consequent spiral of deeper wells and receding underground water was only the first of a series of interconnected and mutually reinforcing vicious cycles that drove depletion of the aquifer. In another vicious cycle, trees and other plants that depended on underground water died because the water was beyond the reach of their roots. Without the plants protecting the soil, erosion increased and johad ponds filled in more rapidly with silt. In addition, less vegetation meant less transpiration (evaporation of water from plant leaves), which resulted in less rain. Monsoon seasons became shorter, from 101 days in 1973 to 55 days in 1987. The result was even less rainwater to replenish the aquifer.

Another vicious cycle was social. Before the decline of the aquifer, wells had provided irrigation water to grow a crop during the dry season. Now wells were drying up and the supply of irrigation water for a dry-season crop was declining. Many farmers were down to a single harvest in the rainy season. The land could no longer support the families who lived on it, and many families had to split up. Able-bodied young men migrated to the shantytowns of cities like Delhi. They sent home cash to support their wives and children. Back in the villages, the wells were dry and village forests, their source of firewood, had perished for lack of water. Women and children had to spend up to 10 hours a day walking to distant locations to fetch firewood and water, hauling the water home in ceramic jugs balanced on their heads. There was no time for children to go to school. Women no longer had time for all their household chores, nor did they have time for extra economic activities to supplement family income. Community institutions became even weaker, and people no longer had time for community obligations such as maintaining johads, a final blow that rendered johads a fading memory of the past.

Logging Alwar’s forests had set in motion a chain of events that dried up the aquifer and tore away the people’s hopes for the future. The downward spiral seemed irreversible. But events would show that it was not.

Return of the Johad

Water was not on the mind of an idealistic, 28-year-old doctor, when he stepped off the bus in Alwar District in 1985. Rajendra Singh was hoping to start a medical clinic. The son of a well-off landowner in the state of Uttar Pradesh, Singh had earned a degree in Ayurvedic medicine, a traditional Indian system that bolsters the body’s ability to heal itself. After graduation, he had moved to Jaipur, the capital of Rajasthan, and joined Tarun Bharat Sangh, meaning “Young India Organization.” The group followed a Gandhian philosophy of helping the poor to help themselves. But Singh was restless in the city. By day, as he worked at a government job, he felt he was only teaching the needy to rely on a bureaucracy. He formed a more radical plan, to work in the most destitute corner of Rajasthan. He sold his furniture and sent his young wife to live with her parents. With four friends, he boarded a bus and vowed to ride to the end of the line. The end of the line turned out to be a village called Kishori.

Kishori did not welcome the newcomers with open arms. Five strange young men from the city were as likely to be terrorists as social workers. After questioning and searching them, villagers relented and gave them shelter in a local temple. A sympathetic landlord in nearby Bhikhampura eventually offered them a two-room house. Singh opened his clinic, but the villagers seemed uninterested in supporting it. He soon found out that they had more pressing needs.

One day, as Singh was walking home from nearby Gopalpura, he got a ride from the driver of a camel cart. The driver was Mangu Patel. As the two talked, Singh learned that Patel owned 200 bighas of land, about 600 acres, in an area where the average landholding was a mere 3 to 6 acres. By local standards, Patel was a wealthy man. But he could not support his extended family. He had three grandsons running bicycle taxis in the city of Ahmedabad, 430 miles away. Each made 30 rupees a day, about $2.43 in U.S. dollars. It was more than they could earn by farming. Twenty years later, Patel still recalls that first meeting with Rajendra Singh: “I asked him, ‘Why are you here, wandering around? Don’t you have any work to do?’ and he said, ‘I am here to do some social work.’ “He had planned to work for the education of children and health projects, but I was the person who told him ‘No, the immediate need is for water. If you work for water, we will help you.’”

At age 60, Patel was old enough to remember a time when the johads had been full of water instead of dirt. On his suggestion, Singh and two colleagues took up pickaxes and spades and began to dig out one of the johad ponds. At first, the three worked alone. But Patel offered grain to anyone who would help. In a time of water scarcity, food was a powerful enticement to pitch in. After seven months, the johad had been excavated to a depth of 15 feet. Singh and his colleagues set down their shovels and awaited the monsoons.

Rain fell on Rajasthan. As luck would have it, the monsoon of 1986 was the region’s first significant precipitation in four years. By the end of the season, the pond was full. And something unexpected had happened. A neighborhood well, one that had long been exhausted, had begun flowing again. Gopalpura had created its EcoTipping Point.

Trickling up

Water was not all that began flowing. The rebirth of rainwater harvesting set loose a cascade of constructive forces, in Gopalpura and beyond. The effects ping-ponged from ecosystem to social system and back, and the momentum got stronger and stronger, as both systems began to heal themselves.

The first wave of effects swept through Gopalpura itself. Successful restoration of the first johad inspired villagers to take on a bigger job: a crumbling irrigation dam. TBS helped with technical advice and the villagers contributed 10,000 person-days of labor. By the next monsoon season, the dam was reconstructed, 20 feet high and 1,400 feet long.

One achievement kept leading to another. By 1996, Gopalpurans had built nine johads, covering 2,381 acres and holding 162 million gallons of water. Underground water had risen from an average level of 45 feet below the surface to only 22 feet, and all the wells had water. The ascending aquifer trickled up through the village economy. Well water was once again available just a few steps from home. Moister subsoil allowed crops to thrive with less irrigation. Because well levels were higher, less fuel was needed to pump water to the surface. The expense of diesel fuel dropped 75 percent. The area of wheat fields jumped from 33 to 108 hectares, and some farmers diversified into sugarcane, potatoes and onions. Many of their fields could now produce two crops, one in the rainy season and an irrigated crop in the dry season. As people ate and drank better, so did their livestock. There were more leftover leaves and stems to serve as fodder for sheep, goats and dairy cows.

As their quality of life improved, Gopalpura’s residents realized that their social order depended on the natural one. They had restored one resource: water. They were ready to bring back another: trees. They revived their traditional gram sabha community council, with participation from every family, and decided to reforest 10 hectares along the edge of the village. The trees would help protect the johads, by cutting down on soil erosion. The trees would provide fuel and animal feed, saving villagers another agonizing daily walk. Residents could break off dead branches for firewood, but to protect the forest from overuse, they would be fined 11 rupees for cutting green ones. Any witness who failed to report a violation could also be fined.

To symbolize the villagers’ commitment to their newly-planted village forest, TBS adapted an old religious ritual. The rakhi was a brightly-woven bracelet, worn by family members and friends as a promise of mutual protection. As villagers planted trees, they performed ceremonies in which they tied rakhis around the trunks. “The father of water is the tree,” says Singh, “and the mother of water is the forest. So if your father and mother are not healthy, the children will not be healthy either.”

As village society reassembled, so did its basic unit: the family. Young men came home from distant cities to work in the fields year-round. Their wives, freed from long walks for water and firewood, had more time for housekeeping and child care. Their daughters, no longer needed for hours of chores, had time to go to school. “Now, there are two schools,” says female elder Manbhar Devi of nearby Bhaonta-Kolyala village, “for small children and older children as well. At that time [before rainwater harvesting], not a single girl went to school. Their parents did not let them go to school. Now every family sends both boys and girls to school, and at least they can finish their primary education here in this village.”

With the gift of spare time, some women earned extra money through soap making, carpet making, spinning and weaving. If they needed seed money, they could borrow it from samuhs, revolving loan funds started by the women themselves. Phuli Devi belongs to a samuh in nearby Bhikampura village. “They are collecting 100 rupees per month,” she explains. “And whenever we need it, someone in the collective can borrow it at a very small interest rate, say 2 rupees per month. Ten or fifteen women come together and pool their money. “We take the loan from the self-help group whenever we need to. And so because of this, we can solve so many problems, nobody needs to migrate from this place.”

From Vicious to Virtuous

Feedback loops are the key to EcoTipping Points. They explain how a small-scale action can set off large-scale change. The rebirth of rainwater harvesting in Rajasthan was an EcoTipping Point “lever” that reversed the vicious cycles driving decline, transforming them into “virtuous cycles” that propelled restoration. For Golpapura that lever was restoration of the first johad. After years of taking too much water out of the ground, the villagers began to put it back. The same forces that were running the region into ruin changed course and began to rebuild it. The virtuous cycles were mirror images of the vicious cycles that preceded them:

- Success breeds success. As their wells filled with water, villagers were encouraged to build more johads, bringing even more wells back to life. They revived the traditional gram sabha village council, which planned, built and maintained more johads. The rewards of united action made village social institutions stronger, inspiring more community action to improve the village in numerous ways.

- Trees and underground water. The rise in the water table encouraged villagers to plant trees. The trees and other vegetation protected the soil, reducing erosion and siltation of johads, allowing more rainwater to seep underground and raise the water table even more.

- Community manpower. Once there was enough water for a dry season crop, young men moved back from cities to the village, providing more labor to construct and maintain johads.

Ripples in Rajasthan

Multiply Gopalpura by 750 villages, and you can imagine the power of an EcoTipping Point. As visitors carried the news home, other towns constructed their own johads. The practice spread further as jal yodhas, or “water warriors,” went on evangelical walking tours, called padyatras. By 2005, TBS counted 5,000 structures in 750 villages, covering 3,000 square miles over five districts. Alwar’s forest had spread 33 percent in fifteen years. A survey of 970 wells in 120 villages found that all were flowing – including 800 that had been dry just six years before.

Gujar Kanhaiyalal, a resident of Bhaonta-Kolyala, recalls the vivid change. “In 1985 to 1988 there was a big drought in Rajasthan. In Bhaonta there were 20 wells, but only two or three had water. But in the next drought, from 1999 to 2002, not a single well dried up.” In Kanhaiyalal’s village, johads brought a dead river back to life. In 1990, he and his neighbors built a catchment dam across the dry Arvari riverbed. After the monsoons had filled the new basin, a small stream sprang up, downhill from the dam. It ran a few weeks. As they built more structures to recharge the aquifer, the stream ran for a longer time, until in 1995, it was a river running all year long. After that, other rivers that had gone dry also resumed year-round flows.

The new rivers and watering holes provided sustenance for wild animals. Bhaonta-Kolyala reforested 1,500 acres of the neighboring hills and declared it a people’s wildlife sanctuary. Named after the local deity Bhairon Dev, it provided habitat for birds and mammals, such as sambar deer, nilgai antelopes, porcupines and jackals. Villagers caught glimpses of leopards, which they had not seen in twenty years.

So valuable were the resurrected rivers that they drew another predator: state government. Officials had largely ignored the watershed, but now, the fisheries department claimed the Arvari’s water and its creatures as state property. It sold fishing contracts to private companies. Realizing their hard-won resource could be lost, 70 villages along the river formed the Arvari Sansad or river parliament. The body had no legal standing. But it organized mass protests and got the contracts revoked. Today, the river parliament meets twice yearly to tackle new challenges.

The Arvari conflict was not an isolated problem. As villagers created new resources, they sometimes stirred up the same social forces that had plundered their old ones. But this time around, their village councils did not collapse into disunity. Instead, they got stronger. The same momentum that had restored their countryside and their communities was also restoring their will to defend them. Two years after Gopalpura had planted trees, government officials cited residents for encroaching on public land. The state flattened the forest and slapped a fine on TBS. But after a two-year struggle, officials reversed themselves. They granted the village an additional 10 hectares, along with 10,000 rupees for tree-planting.

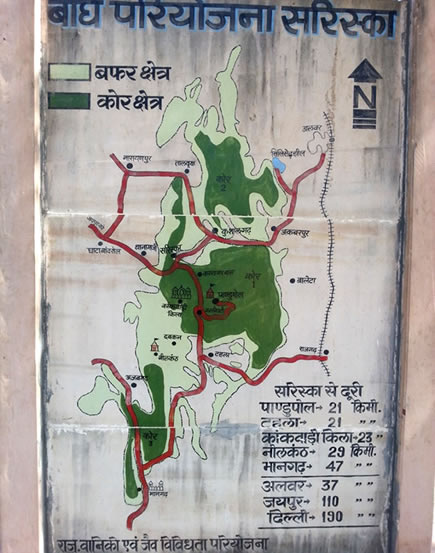

TBS defied the state again in the early 1990s. In the heart of Rajasthan lay a national park called the Sariska Tiger Reserve. Its long-time residents were building johads, but their wells were not filling up. The problem turned out to be illegal marble mines, which were sucking the underground water dry. In spite of threats from the “marble mafia,” TBS sued to close the mines. More than once, Singh and other organizers were beaten by hired thugs. But the group finally won a Supreme Court order, shutting down 471 marble mining pits. Villagers got their underground water back, and more tigers roamed the reserve.

As recently as 2001, the state ordered TBS members to destroy a dam at Lava Ka Baas village or face arrest. The residents, however, would not let the bulldozers near. For two months, they held a vigil over the structure, night and day. In the end, the authorities backed down.

Today, the water warriors of Rajasthan are challenging the government on a national scale. In 2002, the national government announced a plan to help 100,000 villages that lacked a local water supply. The plan would spend up to $125 billion on a centralized network of canals and pipelines, to hook up 37 river basins. Much of the money would come from private companies. Just as Alwar’s forests had been snatched from the people, the nation would hand over vast quantities of its water to corporate ownership. Farmers would have no control over its availability or its price.

Singh has a different vision. He maintains it is far cheaper to help villages create and control their own water supplies than to build more gargantuan dams and ditches. TBS and other groups have joined in a National Water Convention and a national walking tour, setting foot in 30 states. Singh compares his peaceful warriors to another independence campaign, 70 years earlier, when Gandhi made spinning wheels and homemade cloth or khadi into symbols of a self-sufficient India. “If Gandhi were alive today, what would he be doing?” says Singh. “Instead of using the khadi as the symbol, he would be making johads, because today the biggest exploitation is underground water mining and the commercialization of water.”

Rainwater harvesting in Rajasthan. A johad is a dam that collects rainwater to channel it into the ground to replenish the supply of underground water.

A wheat field, irrigated during the dry season.

A mustard field, irrigated during the dry season. Mustard production is a major source of income for Rajasthan's farmers.

Restored village forests provide firewood close to home. The firewood is used primarily for cooking.

Local transportation.

Gram sabah (traditional village council) meeting.

A village elder who provided guidance for reconstructing the johads in Golpapura.

A johad in Golpapura village during the dry season. Part of the village forest is in the background

A well in Golpapura village provides water for crop irrigation, livestock, and washing clothes.

A village well. The ditch at the right of the photo transports water to irrigate the wheat field in the background. You can see how dry the land is beyond the wheat field, where there is no irrigation.

A well provides drinking water for people and livestock.

A Golpapura woman walks to a nearby well to fetch water.

Ingredients for Success – Rainwater Harvesting in Rajasthan

- Author: Gerry Marten

- Shared community awareness and commitment. Strong democratic institutions and genuine community participation are prominent in EcoTipping Point stories. Of particular importance is a shared understanding of the problem and what to do about it, and shared ownership of the action that follows. Communities move forward with their own decisions, manpower, and financial resources. Working only for food, a number of Golpapura villagers joined the team to restore the first johad. The following year, a larger dam was restored by the residents with an estimated 10,000 person-days of labor. Traditional participatory village councils (Gram Sabha), which featured representation from every family and reached decisions by consensus, were revived to manage dam construction. The Gram Sabha also initiated community reforestation projects. These cooperative efforts strengthened village solidarity, which was later crucial for the nonviolent civil disobedience that resisted government efforts to shut down the johads.

- Outside stimulation and facilitation. Outsiders can be a source of fresh ideas. While action at the local level is essential, a success story typically begins when people or information from outside a community stimulate a shared awareness about a problem and introduce game-changing ideas for how to deal with it. Five young men from the group Tarun Bharat Sangh ("Young India Organization") came to the village of Gopalpura intending to set up a health clinic. But they found the greatest need was water and, on the advice of a village elder, began to work on restoring traditional earthen dams (johad) for rainwater catchment and underground water replenishment. They were helped by outside professional engineers.

- Enduring commitment of local leadership. Trusted and persistent leaders inspire the deep-rooted and continuing community commitment and participation necessary for success. Rajendra Singh, one of the five young men from Tarun Bharat Sangh, maintained his role as leader, and Tarun Bharat Sangh has actively facilitated the construction of johads in more villages by hosting thousands of visitors to see what was achieved in Golpapura and insisting on contracts that rigorously specify labor and cash commitments by villages that want Tarun Bharat Sangh to help them build their own johads.

- Co-adaption between social system and ecosystem. Social system and ecosystem fit together, functioning as a sustainable whole. Communities create a "social commons" to fit their "environmental commons." Effects from the rebirth of rainwater harvesting ping-ponged from ecosystem to social system and back, and the momentum got stronger as both ecosystem and social system began to heal. The communally-oriented traditional Gram Sabha councils were able to manage communal enterprises such as johad and village forests with an effectiveness not found in conventional village councils (pancharat). Young men came back home from the cities, providing additional labor for johad restoration. Villagers also organized tree planting and protection of the village forest. This mobilization of manpower led to the restoration of the environmental support system, so that once again the ecosystem provided for people's needs.

- "Letting nature do the work." EcoTipping Points give nature the opportunity to marshal its self-organizing powers to set restoration in motion. Once the dams were constructed, one had only to wait for the monsoon rains. The ponds behind the dams filled with rainwater, which percolated into the underground water, and wells began to flow again. Underground transport of the water from dams to wells was achieved at no expense for infrastructure such as pipes or ditches, and no water was lost to evaporation. Rivers and streams were restored to year-round flows, providing further "free" water distribution. The higher water table meant that crops could grow with less irrigation, and trees could grow close enough to villages to reduce the effort for firewood collection. The recovery of forests reduced soil erosion, protecting the johads from siltation.

- Rapid results. Quick "payback" helps to mobilize community commitment. Results from the very first johad pond were seen in just a few months. During the monsoon it filled with water and a nearby well began flowing again. This quick payback inspired more dam building. Ten years later there were 10 such ponds in Gopalpura, holding 162 million gallons of water. The practice eventually spread to 750 other villages.

- A powerful symbol. It is common for prominent features of EcoTipping Point stories to serve as inspirations for success, representing the restoration process in a way that consolidates community commitment and mobilizes community action. The leader of TBS, the non-profit organization stimulating these changes, became a symbol of the movement throughout the region. To underscore their commitment to the trees, villagers tied colorful rachis (kinship bracelets), around their trunks, a symbol of family protection.

- Overcoming social obstacles. The larger socio-economic system can present numerous obstacles to success on a local scale. The restored resources – underground water, village forest and river fisheries - attracted the interest of the government, which sought to claim the resources as state property. But the "water warriors of Rajasthan" had become well organized and were able to defend their resources.

- Social and ecological diversity. Diversity provides more choices, and therefore more opportunities for good choices. With water and firewood just a short walk away, women had time to start cooperatives, selling milk products, handicrafts, and soap, diversifying sources of income. Children had time to go to school, including girls who had not previously had the opportunity, bringing new skills and confidence to the village. The area of wheat fields jumped from 33 to 108 hectares, and with the land and sense of possibility restored, some farmers diversified into sugarcane, potatoes and onions, which increases the chance that if one crop is having a bad year another crop is there to help the community thrive.

- Social and ecological memory. Learning from the past adds to the diversity of choices, including choices that proved sustainable by withstanding the "test of time." Reviving the tradition of building johads was possible because elders remembered how to construct and maintain them. The traditions of the Gram Sabha village councils, voluntary labor, and foot marches ensured success and the spread of success to other villages. Nature contains an evolutionary "memory" of its ecological design for sustainability.Because of ecological memory, the restored rivers and forests provided habitat for wildlife that had not been seen in the area for many years.

- Building resilience. "Resilience" is the ability to continue functioning in the face of sometimes severe external disturbances. The key is adaptability. The forest helped to maintain and protect the watershed. Underground water storage reduced evaporation, and ensured water supply for household use and dry season irrigation even in times of low rainfall. The social organization and community solidarity were also strong protections. The circle of positive effects—more water, more agriculture, more vegetation, less erosion, more water—and the related social benefits (e.g., men returning to the village) ensured the sustainability of the gains. It was no longer necessary for women and children to haul water from distant sources. As a consequence, women had more time for housework, child care, and supplemental economic activities, while children had time to return to school and the education that could provide them a more secure future.

Feedback Analysis– Rainwater Harvesting in Rajasthan

- Author: Gerry Marten

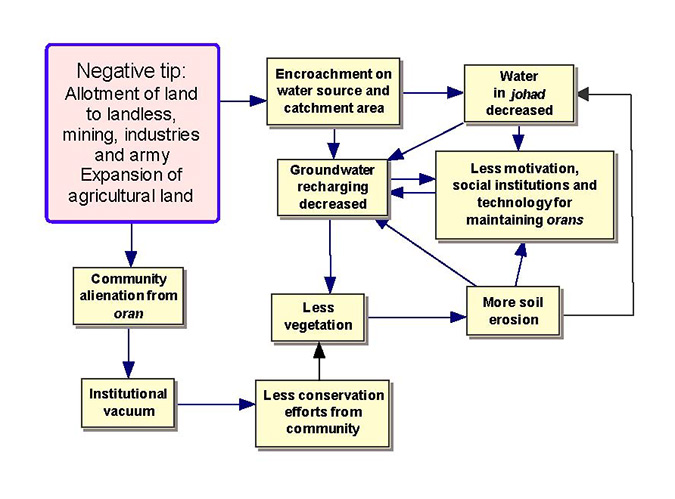

Negative Tip

The negative tipping point in this story was introduction of commercial logging. A system of interconnected and mutually reinforcing vicious cycles was set in motion by the cascade of effects from the logging:

- Logging reduced the forest’s protection of the watershed from soil erosion. Soil erosion and the sediment load in rainwater runoff increased. More sediment was deposited in johad ponds, reducing their capacity to channel water to the aquifer. With less water input to the aquifer, the water table slowly dropped. Trees and other vegetation died when the water table fell beyond reach of their roots. The loss of vegetation led to even more erosion and sediment in the runoff.

- Villagers compensated for the drop in the water table by using tube well technology to dig deeper wells. That lowered the water table even further, forcing the digging of even deeper wells.

- More sediment deposition in the johad required more labor to remove it. This, and the fact that the water supply was shifting to deeper and deeper tube wells, reduced the villagers’ motivation to maintain the johad. As they fell into disrepair, the johad gradually went out of use along with the social institutions and technology for maintaining them.

- Eventually the water table was so low that even the deepest tube wells were drying up. So did the irrigation water necessary for dry-season agriculture. Men moved to cities to find work, leaving villages without the labor supply needed to maintain the johad. This accelerated decline of the johad and depletion of the aquifer even further.

Positive Tip

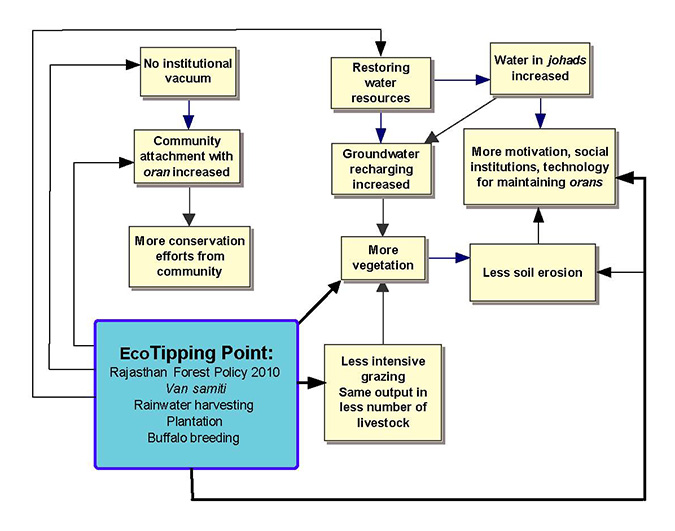

As one can see in the diagram, the four vicious cycles listed above were interconnected and mutually reinforcing.

The end result was disappearance of the johad and loss of the local water supplies and village forests. Women and children were cast into a nightmare of walking long distances to collect water and fuel wood. Children had no time for school, and women had little time for other family responsibilities and economic activities.

The positive tipping point was the restoration of a single johad in Gopalpura village, along with restoration of the traditional gram sabha village council to manage it. The ensuing cascade of effects reversed three of the feedback loops in the negative tip, transforming the vicious cycles to virtuous cycles:

- Water soon returned to wells near the johad, stimulating the villagers to restore more johad. The technology and social institutions for restoring, maintaining, and building new johad, evolved as more johad were put into service.

- The water table rose, filling more wells and restoring irrigation agriculture. Men moved back to the villages, providing the labor necessary to restore, build, and maintain even more johad.

- With the water table once again close to the surface, the villagers planted trees to restore the village forest. The forest not only provided firewood but also reduced soil erosion, reducing sedimentation of the johad and making them easier to maintain.

The virtuous cycles continued until all village wells were flowing and the village locked into a sustainable water supply. Women and children no longer had to spend long hours getting water and firewood. Children returned to school and women returned more attention to family and economic activities. A new virtuous cycle was set into motion when people from other villages heard about the success in Gopalpura and came to see what happened. Johad spread to hundreds of villages.

Restoring Rajasthan’s Traditional Earthen Dams for Rainwater Harvesting and Groundwater Replenishment

- Author: Amanda Suutari

- Based on site visits in December 2004 and March 2005

The Water Problem

Historically a water-rich country, India is now facing a water crisis. Changes such as the Green Revolution, economic growth, and urbanization have all put enormous pressure on its freshwater resources. With 16% of the world’s population but only 2.45% of the world’s land area and 4% of the world’s water resources, India’s demand for water is outstripping its supply. Meanwhile, the population is increasing by 19 million every year, the equivalent of a new Canada every year and a half. Half the nation’s inhabitants are expected to make a drastic demographic shift to urban areas by 2050.

The Central Groundwater Board of India projects that the reservoir of groundwater will dry up by 2025 in up to 15 states if the current rate of exploitation continues. Punjab state is estimated to have already used up 98% of its groundwater, which means that if current trends continue, this breadbasket of the nation could turn into a desert. Moreover, water distribution is dramatically unequal: from 9000 millimeters of rainfall in Meghalaya in the west of India to 100 millimeters in western Rajasthan in the east of the country. The reservoir of groundwater, estimated at 432 billion cubic meters, is rapidly being depleted with major metropolitan centers estimated to go dry by 2015.

Water scarcity is a familiar subject in the media and has become a major political flashpoint. Conflicts, sometimes violent, have erupted at all levels--between states, regions, urban and rural areas, upstream/downstream populations, and along national borders. Sometimes conflicts surface along ethnic lines, as between the Bishnoi and Bill peoples of Rajasthan. While many of the ethnic conflicts are rooted in complex historical, ethnic and religious issues, scarcity now plays a critical role. Some of the major hotspots which simmer under the surface in years of stability and erupt in years of scarcity are the conflict between Karnataka and Tamil Nadu state over the Cauvery River Basin; between India and Pakistan over the Sindh river; and historical conflicts between India and its downstream neighbor Bangladesh over the Ganges and Bramaputra Rivers. Bangladesh blames Indian mismanagement of the Ganges for floods which repeatedly washed through the country.

Under pressure from multilateral development banks, the Indian government has tended to look for solutions in markets and large-scale, costly infrastructure. Dams, diversion projects, and the controversial plan to interlink the major rivers have been widely criticized for displacing and impoverishing villagers, wreaking havoc on wildlife, and pushing India further into debt. South of Rajasthan in neighboring Gujarat state, the notorious Narmada dam has been the subject of international campaigns because of its astronomical costs and its flooding of villages that is expected to displace over a million rural dwellers.

Rainwater Harvesting in Rajasthan

Against the backdrop of urban water shortages and increasingly volatile friction over water sources, the groundbreaking revival of traditional rainwater harvesting initiative in the arid state of Rajasthan has received nationwide attention.

Rainwater harvesting (RWH) is not new to India; in fact, it has been a major source of irrigation on the subcontinent for centuries. Archeological evidence of water harvesting tanks date back to around 1500 BC, and reference is made to them in ancient texts. One study cites evidence of sophisticated irrigation systems and hydraulic structures that used water harvesting as early as 5,000 years ago. In the medieval period rulers in southern parts of India financially supported the construction of village-level structures for rainwater harvest or storage running into the tens of thousands.

Traditionally water and forests were seen as intimately linked. Both were bound up in spiritual and social traditions which forbade cutting of trees or misuse of water. The Rajasthani people co-evolved rainwater harvesting traditions that practiced water conservation so that their naturally arid region did not translate into water scarcity. Water was considered sacred, and an "amrit," a nectar or ambrosia. Around communal ponds, people tied threads around the trees in worship of them. Various ceremonies marking important milestones in family life such as births, deaths and marriages often involved water or some kind of ceremony around the village well. It is also common for daily offerings of water to be made to the deity of the village temple. In the forests people believed deities lived in the trees. In Sariska, people saw the degradation of the forests by the destructive mining activities as a sign of anger from the gods with rain and water being withheld from them as punishment. The Peepal and Banyan, their sacred trees, would not grow, because there was no water or sand to hold them. They also believed deities were angered by the blasting and dumping that were disturbing the animals that lived there.

Despite regional variations, these beliefs and practices prevailed in the region for centuries, if not millenia, until the 19th century. Changes started to take place with the arrival of colonial Britain and accelerated after Independence. Control of formerly communal forests and water resources were taken over by centralized authorities. Based far away and with no local ties, they had little interest in or understanding of local conditions. They frequently opened these resources up to exploitation by commercial mining and logging companies. Over the years, the dependence on government to manage their resources eroded traditional communal management institutions and people lost their sense of stewardship for their village forests and watersheds. Wooded areas became denuded and overgrazed, and water harvesting structures became neglected.

The State of Rajasthan is the second largest in the country, covering 34.3 million hectares, over 10% of the total geographic area of India. It comprises 5% of the country’s population. It is divided into 30 districts, which are further divided into blocks. There are 15.7 million hectares of arable land. It is among the driest states, with total surface water resources only about 1% of India’s total surface water. All rivers are rainfed, with 14 major river basins and 59 sub-basins. Surface water is found mostly in the south and southeast of the state. There is a large area in the west which has no distinct drainage basin. The scarce water resources are distributed unevenly temporally as well, with most of the rainfall occurring during the monsoon. Large-scale infrastructure, such as dams, reservoirs, and diversion canals are available to about 30% of the state’s population, but not without significant social and environmental costs. Groundwater mining is causing water tables to drop up to a meter per year in some areas.

Rajasthan is a historically and culturally rich region, and was once home to very wealthy merchants and maharajas. It is located along the trading routes where camel caravans crossed the western part of the state. There are various ethnic groups in Rajasthan, speaking Hindi or Rajasthani or, because they are similar, a patois of both. Hindu is the dominant religion, followed by Islam. One major ethnic group is the Rajputs, warrior clans known for their bravery, whose dynasty peaked at the beginning of the 16th century . They were overtaken by the Mughal Empire but struggled for independence as the Mughal empire declined. Allying themselves with the British, they managed to remain an independent state, but during the ensuing extravagance and escalating corruption their wealth and privilege were squandered. Today it is one of the poorest regions in India. The female literacy rate is lowest in the country, with 1.7% compared to 87.8% in Kerala in the south. The child labor rate, on the other hand, is high.

The Negative Tip

The Alwar District lies northeast of Jaipur in the northeast part of Rajasthan, covering an area of 8,380 square kilometers. It has a population of nearly two million people, living in 1,991 villages and five towns. It is divided into eleven blocks, or administrative subunits. It was a princely state during the pre-Independence period, merging with the Indian union in 1949 with the birth of Rajasthan. The area is at the northern edge of the Aravalli mountain range that extends from south Rajasthan to Delhi. Its climate is semi-arid with an average rainfall of 350-400 mm distributed unevenly throughout the season. It is mainly an elevated, rolling plateau interrupted by the hills and rocky ranges of the Aravallis. Thought to be one of the world’s most ancient mountain ranges, geologists say the Aravallis belong to the pre-Cambrian period of 1,500 million years ago. The ranges run from Delhi to near Ahmadabad in Gujarat state, with peaks rising in the southern portion to about 6,000 feet near Mout Abu in Raja. The mountains are composed mainly of shrub lands with forests of dry, deciduous vegetation. They provide habitat for endangered species such as the panther, leopard, and four-horned antelope. Forest cover is the best in Rajasthan and covers 10-15% of the district.

The main inhabitants of the region are the tribal Gujjar, Balai, Rajput, Kumar and Meena. The main sources of livelihood are agriculture, mainly staple crops such as wheat, mustard and pulses, and livestock such as cows, buffalo, sheep, goats and camels. The crops and animals often vary depending on the ethnic group. Landholdings are small, averaging between 1.5 and 2.5 hectares in area. In the forested areas, there is less agriculture and more emphasis on minor forest products. Houses are made of stone, mud, and thatch.

Ironically, the Alwar District was once locally known as “naha," meaning an area with a high water table. This was due mainly to the practice of harvesting rainwater. Unfortunately, just prior to Independence, a wealthy prince sold off logging rights to the local forests. They were subsequently cleared without the consent of the people whose livelihood depended on them. Although the changes that occurred in the region over the years are a result of complex interacting forces, this act of clearing the forests set in motion a wide-ranging web of effects. First, it caused severe soil erosion during the monsoon. Rains ran off the mountains and land and escaped, carrying topsoil into water tanks. As they lost their de facto ownership and sense of stewardship of the forests, villagers became alienated from their long established communal forest management institutions. Since water and forest management were inseparable to the people, this also eroded their water conservation practices. Water harvesting structures silted up and became neglected. At the same time, state control of water resources created a further disincentive for villagers to maintain their traditions. They became increasingly dependent on the distant bureaucracy to provide water sources in the form of wells, diversion canals, and water harvesting structures. These were essentially ill-conceived projects foisted on villagers without their participation and without in-depth knowledge of local conditions. As such neither the government nor the villagers themselves properly managed or maintained them.

Paradoxically, as the natural resources began providing less of their formerly reliable services, pressure on them intensified. Wells were dug deeper to capture receding water. This "groundwater mining" caused water tables to fall further. This in turn reduced crop yields to one harvest per year and lowered livestock productivity. It also increased the workload of women, who were walking much longer distances to find water sources. Once self-sufficient villages were pushed into the cash economy as able-bodied men left the countryside for towns and cities in search of work. This out-migration put an added population pressure on growing cities as well as eroding the social fabric in the villages. Absent men contributed little to the upkeep of their community, increasing the pressure on women and female children to care for children and the elderly in addition to the normal farming, household, and water fetching responsibilities. With falling crop yields, food security for villagers and livestock was low, and forested areas were overgrazed by hungry livestock. Increasingly, destitute villagers were clearing forests and grazing malnourished livestock. Despite the fact that they may have been aware of the long term unsustainability of their actions, they were forced to focus on daily survival needs.

The Positive Tip

Around this time, 1975, a small youth organization known as Tarun Bharat Sangh (Young India Organization), or TBS, formed in response to the destruction wrought by a fire on the campus of Rajasthan University. A group of volunteers came together to offer assistance, medical help, food and shelter to the victims of the fire. After this initial project, the group decided to stay together and shifted their attention to rural development. They began to learn about poverty in the villages, and the impact of the Green Revolution and economic liberalization on villages.

In 1984 they moved into Bhikampura village in the Alwar district with the goal of introducing some health and education programs. The villagers were skeptical. Jaded by the misguided efforts of outside aid organizations, they had little faith in TBS’s vision of development. An older wealthy farmer from the neighboring village of Gopalpura, Mangu Patel, told TBS worker Rajendra Singh that they didn’t need hospitals and schools, they needed water. At that time, the region was in the midst of a severe drought. Village wells had dried up completely, and urban migration had reached a peak of 3-4 people from each family. Patel offered to show him how to repair a used traditional water structure known as a johad-- a water harvesting structure that traps the monsoon rains, recharging the groundwater that supplies the village wells. It was difficult to get younger village men to volunteer their labor to the project, as it meant giving up wages in town. Finally a "test case" on an existing johad was launched with the technical help of the irrigation department. Within two years, the results of the work were apparent. The monsoon of 1986 came and went, leaving water tables higher for a longer period of time than before. This prompted the villagers into the more ambitious task of masonry repair of an irrigation dam. The same engineer gave them further guidance along with encouragement from TBS. For this project, some villagers sent for family members working in the towns. The structure was completed in time for the 1987 monsoon. This success sparked interest in neighboring villages. The next year, more new structures were built or repaired. Eventually critical mass was achieved, and today there are over 10,000 johad water harvesting structures in the region. Badri Prasad, a local landlord, eventually donated some land near Bhikampura village to TBS. Over the years this headquarters has grown from a two-room building to a complex which houses an Ayurvedic clinic, guest house, kitchen and administrative office.

Because the villages lie along the Aravalli mountain range, the topography is complex. One study, “Johad” (1998) states that “it would not be right to make any statement regarding the exact increase in ground water level.” At the same time, it acknowledges that “Johad construction plays a major role in recharging groundwater.” It cites a survey collaborated on between TBS and Action for Food Production (AFPRO) which was conducted first in 1988, which suggested that out of 970 wells in 120 villages, only 170 wells were operational and the rest were dry. The same team conducted another survey in 1994, 6 years later, and found that all 970 wells were in use and supplying water year-round. Another evaluation report suggests that in the regions harvesting rainwater, groundwater has risen by 20 to 50 feet in 10 years. A TBS study finds that between 1987 and 1997 in Gopalpura, where the project started, the water column of the village wells increased during the monsoons from 15 feet to 55 feet. Dry season levels also increased from 10 feet in 1987 to 35 feet in 1994.

Spin-Offs

Just as the deforestation of the hills caused the social system and ecosystem to slide into an unhealthy stability domain, this catalytic action of building the water harvesting structures has had multiple spin-offs. First, it significantly improved the quality of life for the women. Freed up from the drudgery of walking many kilometers to fetch water, women had more time and energy to spend on priorities such as health and child care. Female children, no longer needed to help their mothers at home, began to go to school. With a year-round supply of water in wells, new fields, formerly "wasteland," were opened up for cultivation and a second--and sometimes even a third-- annual crop were added. This dramatically increased food security. When the water table is higher, less diesel fuel is used for the pump to extract the water, so fuel use is reduced. Also, high groundwater levels mean less water is needed to irrigate cropland.

Meanwhile, with livestock able to drink from johads, and with more agriculture, there is more crop residue to be used as fodder for animals. In this way the health and productivity of livestock improved. With this extra income and security, and new responsibilities for men in the villages, migration to the cities slowed down. This has helped restore family and social bonds, and has relieved some of the agricultural burden on women who were compensating for absent family members.

Among TBS and villagers awareness grew of the need to protect and regenerate the forests to prevent soil from silting up the newly built johads. This rekindled a holistic perspective and began to revive forgotten communal forest and water management institutions. It also recreated a sense of ownership among villagers who had now invested their energy and time into these resources. It motivated them to come together against the power structures that were threatening them. In the region’s Sariska Wildlife Sanctuary, marble mining had seriously impacted the forests and water supply. The villagers living in the reserve joined forces with TBS to oppose the mining and stop poaching, and in 1991 successfully managed to stop mining in the reserve. This has helped the water tables to rise, the forest to regenerate, and has increased the amount of wildlife in the sanctuary, including the endangered tiger.

An unexpected result of the rise in groundwater levels is the revival of two seasonal river basins, the Arvari and the Ruparel, which now flow nearly year-round. When the government of Rajasthan sold a fishing license to a commercial fisher, villagers united in opposition and forced it to rescind the license. This prompted all the villagers living in the basin of the Arvari to form the Arvari Sansad, or Arvari River Parliament, to make rules on its use and take measures to protect it from other outside interests. Some villages also began their own independent councils, where they discussed the water and forest resources and set up regulations governing their use.

These developments have had benefits which reached from the ecosystem into the social system. The solidarity and confidence gained by the villagers, encouraged by TBS, have triggered the launch of other projects and village councils that regulate the use of water and forest resources. At least one member from each household is part of these village councils, or Gram Sabha. While they can create regulations governing use of water and forests and enforce penalties, they are not recognized by the government and have no legal power outside the village. An example of rules governing forest use, for example, is the limits on areas where people may bring animals for grazing. Sometimes certain areas of the forests are off-limits for given periods, or the age of the trees may be used as limits for particular animals. For example, sheep are allowed only after trees are tall enough for their leaves to be out of the reach of the sheep. Similarly a cow would not be allowed in a given area until trees grow out of their reach, while longer periods would be given for camels, and so on. Some Gram Sabha have also set up a village fund, or Gram Kosh, which is put towards village maintenance or investment in income generation or other future projects. This has given villagers the financial means to achieve common goals.

Another democratic structure emerged after the revival of the Arvari River in 1994, when villagers realized there was a need to protect the newly revived river from commercial interests. After banding together to successfully defeat efforts by the Fisheries Department to issue a fishing license to a commercial fisher in 1996, they went on to form the Arvari Parliament. The parliament is made up of 70 villages along the river basin, with one or two representatives from each village. Currently there are 150 members, 30 of whom are female. The parliament normally meets for two consecutive days every six months. These biannual meetings are held in different places each time, usually in a village which is facing some water or forest management problem. This provides motivation and inspiration to the host village as they hear members from other villages share their success stories. Outside of these regular meetings, a core group of 22 meet more frequently. One coordinator and two vice-coordinators are nominated every five years, but the membership can decide to change the coordinator if they’re not satisfied, or if he/she misses more than two meetings, as sometimes happens.

With the Gram Sabha and the Arvari Sansad, the villagers have de facto control over the river and forests. For the time being this reinforces the institutions of communal management. However, because they do not have official government authorization of this control, there is always the possibility that they will lose these rights should the government or commercial interests enforce a claim to them.

The emergence of women’s Self-Help Groups has had a huge impact on the community. A group of village women contribute a certain amount of money to a pool and deposit it into a cooperative bank. This acts as a "revolving credit" fund where whoever needs it can borrow money at low interest. They must then pay it back as quickly as possible for the next person to borrow it. The resulting increase in solidarity and entrepreneurship among women has encouraged them to play a more active role in this deeply patriarchal society. Some of the micro-enterprises developed include soapmaking, selling milk and milk products such as ghee, carpetmaking, spinning and weaving. Improvements have been made to education and health care. There has been a shift in priorities away from the conventional symbols of progress such as electricity and roads, and towards self-sufficiency, reinforced by the summer padyatras, or foot marches, which promote this value. There have also been some changes in socially oppressive customs. The dowry system, ostentatious, costly weddings, purdah where women must cover their faces and stay inside, and child labor in the carpet industry have all been actively discouraged. As community cohesion strengthened in Gopalpura, they became the first village to give up the making and consumption of alcohol and it is still today a "dry" village.

Replication

TBS and villagers have disseminated their approaches in several ways based on using local customs. One of these is known as the foot march, or padyatra, which has very old roots in India’s spiritual traditions. In the past, people would wake up early, around 4 a.m., and make a "morning march," walking door to door through the villages singing religious songs to wake up, for example, Krishna, or whatever gods, goddesses, or nature-based spirits were locally worshiped. Sometimes it is also symbolic of awakening not only the body but the spirit. Pilgrims who had a religious message would walk from village to village to disseminate it. Gandhi used and popularized the foot marches as he went through the villages mobilizing them against the oppression of colonial rule, and one of his disciples, Vinoba Bhave, used them during his famous land redistribution movement where he managed to get rich landowners to donate over a million acres of land to landless peasants. Politicians also use the padyatras as a way to get rural votes.

TBS has been involved with three kinds of padyatras. One starts at the beginning of summer, one comes at the start of the monsoon (technically July) during the Rakshabandan festival, and another in October. The people joining the march, the "padyatris," are made up of available TBS workers and other people somehow related to the particular area or village where the padyatra was held. The march begins in one village, where the group stays a few days, and then moves on to the next one as a group. In each village there are ceremonies, cultural events, and discussions on whatever the subject of the march is. If the region chosen is very large, sometimes they break up into groups. Within 40 days they go from village to village. Depending on the distance between villages, anywhere from 15 to 50 villages may be visited.

Funding for the work of building rainwater harvesting structures is usually divided between TBS and villagers, who contribute a quarter to a third of the costs in cash or in kind. Generally the contribution TBS makes is for contracting skilled work such as masonry or specific engineering tasks. Over the years, the contribution of TBS has contracted as that of the villages has expanded. Physical labor is provided by people in the recipient villages. Sometimes villages have a system where grain contributions are sold by the Gram Sabha and the proceeds put toward johad construction or other projects.

TBS receives funding from various sources, from both groups and individuals. It has also been funded for specifically-designed projects by various agencies in Europe, as well as the Ford Foundation, OXFAM India, and some government agencies such as the national Department of Science and Technology, and the state Watershed Department. Sometimes TBS has solicited the contributions of local business. There are some 50 full-time TBS workers, about 200 part-time workers, and hundreds of volunteers spread out across villages in Alwar and neighboring districts. Many are either from villages or stay in the field long-term, returning to the Bhikampura campus from time to time. A few staff members and volunteers also stay at the campus year-round. Rajendra Singh won the Ramon Magsaysay Award for Community in Leadership in 2001. At the campus there is a showcase with various other awards displayed in it. The award given to Bhaonta-Kholyala, the “Down to Earth Joseph C. John Award” in 2000 is documented on the painted map of the water harvesting structures in the village (see photos). TBS continues in its work in the villages but has increasingly extended its reach into the arena of advocacy and influencing policy on water and the environment. It has been instrumental in the formation of a nationwide coalition of civil society groups called the Jal Rasthryia, National Water Coalition, with Rajendra Singh as the head.

Challenges

There will always be important challenges that threaten to derail the progress made in this district. Every time new assets are created, a fresh dilemma emerges over how to manage these assets and protect them from powerful interests from both outside and within. As well, the relationship between various government agencies and these newly mobilized villages has been rocky. It’s important to note that "the government" is not just one entity but a vast array of individuals and agencies among layers of bureaucracy from forest rangers, local police, Gram Panchayat (the elected village councils, different from the self-organized village councils or Gram Sabha), the irrigation department and engineering staff from the latter. A few have been sympathetic from the beginning (like the engineers who donated their technical assistance to repair the first johad in Gopalpura), some have initially been unsupportive but over the years have come to trust and work in partnership with TBS (like the forest rangers of the Sariska Tiger Sanctuary), and others may remain unsupportive if not outright hostile still today. Worse, the bureaucratic tangle of fragmented administrative and legal entities has created ambiguity and confusion for all communities and organizations doing water-related projects. For starters, the Drainage Act (that says that all groundwater and runoff is the property of the state), the Fisheries Act, and the Panchayat Raj Act all have conflicting definitions of both control and ownership of water resources. At the national level, the overlapping Ministries of Rural Development and Agriculture, and the underfunded Ministry of Environment and Forests all work haphazardly at cross-purposes with little coordination among them. As one article states, “In India, water seems to be everybody’s turf but nobody’s responsibility.” Nevertheless, TBS has received financial support from government agencies at the state and national level, and gradually over the years relations have thawed somewhat.

TBS members and villagers have been threatened with arrest, fines and even violence on numerous occasions. In 1987, they were given a notice which quoted the Irrigation Drainage Act, saying that no stream or canal water could be stopped as it "belonged to the government." Villagers and TBS protested that the rain belonged to them and all they were doing was stopping the rainwater from draining away. In 1989, the Alwar district administration slapped a fine of Rs 5,955 (US $150) on Rajendra Singh for planting trees on government land. They fought this for two years, saying that they were planting trees not for any one individual’s benefit but for the common good. In the late 1980s, Rajendra Singh said about legal 377 cases were brought against TBS workers, although he never went to court over any of them as they all collapsed on their own. The legal maneuvering simply strengthened their resolve to continue their work. There were also three rape charges against Rajendra Singh later dropped as baseless. He was also accused of poaching tigers in Sariska, but on the day he was said to have been seen in the reserve, he was in a meeting with government officials about building water harvesting structures.

While building structures in the Sariska Tiger Sanctuary, the government used the Wildlife Protection Act against TBS workers, saying that they were illegally building ponds on forest land. But after realizing the decrease in poaching and noticing the positive changes in the reserve, one official requested them to continue their work, and Rajendra Singh asked for some authorization that they could do so without fearing future accusations of breaking the law. The official, risking a jail term, gave his authorization. This was a groundbreaking change between forest officials and TBS. Their relationship has changed over 17 years from being antagonistic to cooperative. During their campaign to close the mines in Sariska, TBS’s coalition brought a petition to the Supreme Court against the mining, and the judge ordered 417 mines to be closed. At this time they faced intense intimidation by the agents of the mining companies, known as "the mining mafia." They were attacked three times, once in the presence of a retired judge. Because of this, one miner was sent to jail for contempt of court. There was also criticism that TBS’s efforts were insensitive to the needs of workers from the mines who were local villagers who depended on the mining income. However, this ignored the important reality that these mine laborers were formerly farmers or herders forced out of their livelihood due to destruction of their resource base by activities such as mining to begin with. Because life in Bhikampura had become tense and difficult, a padyatra was begun in October of 1993 from Gujarat to the Delhi ridge, which was able to boost the eroding morale of workers. As recently as 2001, the government requested TBS to destroy one of its water harvesting structures at Lava Ka Baas village or face arrest within seven days although no warrant was issued. The people held a vigil over the structure, and two months later the government backed down. In the article “Water Harvesters of Rajasthan,” journalist David Nicholson-Lord writes that Rajendra Singh explains the government’s antagonistic attitude by saying that “officials were hostile to johads because there was no rake-off for them and because self-governing villages are hard to manipulate.”

In a more ominous incident in June of 2002, Rajendra Singh was badly beaten up at a public hall in Aligarh town in Uttar Pradesh State, where he had been invited by a chapter of the Society Towards Ecological Protection to talk about water harvesting. In his speech, Singh talked about how people should depend on their own power and not the government to solve their water problems. During the question and answer session, a man known as Tejvir Singh got up and attacked him as the horrified audience, his young son among them, was forced out of the building by thugs who had accompanied Tejvir Singh to the lecture. An unconscious Singh was rushed to hospital where he spent several weeks in the neurosurgery ward under treatment for a blood clot in the brain. Police caught and arrested the assailant, a known criminal with strong political ties, who had already been implicated in cases of murder, assault and fraud. He has since been imprisoned where he remains today.

Another issue which has implications for the future is the commercial interest in regions rich in groundwater for industrial purposes. Because there is no legal protection to villages who have invested their resources in recharging groundwater levels, they would not be entitled to payment for the use of this water, say, through the generation of royalties. This is relevant because within the last decade the central government has issued notices to medium and major industries to relocate production from the Union Territory of Delhi in an attempt to control pollution and reduce pressure on the environment. As Alwar is outside of the Union Territory but accessible to Delhi, there has been an increase in construction of industrial units along the Delhi-Alwar highway and more projects are being planned, with industries looking to buy land at rates well above market rates. Some of the big farmers have been trying to motivate other farmers to take advantage of this opportunity, with some villagers reporting that the price offered for their land is ten times higher than the market rate.

Another area of concern is the lack of female participation in the village councils or Arvari Parliament. While efforts are being made by TBS staff and villagers to include more women, social norms and customs are strong limiting forces. Of course, responsibility lies on the men to encourage and support the women, and also on women to override these social conventions. There have been some real changes in this regard over the past two decades, but because men and women’s knowledge systems are different, their inclusion in decision-making needs to be made top priority. In “Bhaonta: A Village Wildlife Sanctuary,” Ashish Kothari writes, “Another... concern, though not articulated by the villagers themselves, is the lack of involvement of women in the decision-making. The gram sabha meetings are almost always exclusively male affairs. Women undoubtedly influence decisions via their husbands, but their absence from the direct participation may not be conducive to the kind of participatory decision-making that villagers pride themselves for.”

These challenges will continue to require flexibility and innovation on the part of the village networks and supporting organizations and of course, TBS. Conditions in the Alwar district vary from village to village, and life in this poor region is far from ideal. Change is frustratingly slow and has required patience, courage, and imagination at all stages. There are also the added obstacles–sometimes life-threatening--thrown up by the government and private sector, who will likely continue to do more of the same. The pressure of modernization will have as yet unseen impacts on this region. And of course conflicts and power struggles exist at the local level as much as anywhere else.

It’s not clear whether community cohesion and social action would have mobilized spontaneously or as quickly without the trusted presence and perseverance of TBS members although many of them do come from the villages themselves. Nevertheless, this case has shown how a society can avert socio-ecological crises such as urban flight, famines or resource-based conflicts, and is a rare, living example of alternative development and sustainable, self-sufficient rural existence.

Lessons about EcoTipping Points from the Rainwater Harvesting Story

- Strong local democratic institutions are both a prerequisite and a result of successful catalytic actions. In the communities which had not formed Gram Sabha, (independent village councils), the construction of the johads either failed or were less successful than those which created them. The labor-intensive work of building johad and planting trees demanded unity and commitment from the beneficiary communities. This cooperative effort in turn strengthened village solidarity. This is significant as strong communities are better equipped to deal with powerful interests who are in a position to exploit newly created assets such as regenerated forests or groundwater. In this case, revival of the Arvari and other rivers attracted the attention of the state government. It began offering licenses to commercial fishers, but the villagers mobilized and successfully blocked this action. This prompted villages sharing the Arvari basin to form an Arvari Parliament to coordinate use of the river and prevent further power plays from outside or within.

- Initial short feedback loops--or quick results--motivate and inspire people toward further action, even if the longer-term process of "tipping" ultimately involves more effort. The johads began yielding results within one to three years of construction. In the context of development, fast results are an important motivator as resources are few and people may be too impoverished to make choices for the long term. The construction of johad increased water levels in wells after the first monsoon, which fulfilled immediate needs. This provided encouragement and stimulus to build on the early successes by making improvements on other areas of the watershed through repairs to existing structures, bunding, terracing, planning of more johads, or reforestation efforts.

- ETPs involve natural and social forces doing much of the work. While construction of johads was labor-intensive, once completed, natural processes took over when monsoon rains caused water to be captured and to quickly percolate into the soil, raising the water table and village wells.

- A perceived sense of crisis will motivate people to act. Lack of water was pushing people toward the edge of malnourishment, leaving them vulnerable to crises such as drought, and forcing able-bodied people into cities for work, children out of school, and women on increasingly longer walks to find water sources. While the villagers knew that this was a priority, there was no sense of collective organization to strategize and find solutions to the problem. When TBS came to work on health care and education, a village elder pointed out that long-term necessities were unthinkable in the face of the urgent need for water. By identifying the problem, TBS was able to focus on this higher priority, and eventually enlist support of the villagers in a way they were not able to with their previous development projects.

- The ETP draws on both social and ecological memory. Reviving the tradition of building johads was possible as elders in the village remembered when they were still used and maintained, and were able to offer accurate knowledge of the technical aspects of construction, such as the location, height, and position of the johad. The local custom of "shramdan" or voluntary labor, was crucial in getting the johads built with limited resources. As TBS expanded its operations, other traditions such as padyatra, or foot marches, were key in spreading the message to other villages. Johads had evolved to suit this hilly terrain, and so these features of the landscape helped to capture and store rainwater underground, especially when combined with reforestation of native species.

References

- “Sacred Water and Sanctified Vegetation: Tanks and Trees in India.” Pandey, Deep Narayan, Indian Forest Service, 2000.

- “Johad: Putting Tradition Back into Practice.” UN Inter-Agency Working Group on Water and Environmental Sanitation, 1998.

- “The Promotion of Community Self-Reliance: Tarun Bharat Sangh in Action.” Dr. Margaret Khalakdina, OXFAM India Trust, 1998.