EcoTipping Points

- How do they work?

- Leveraging vicious

cycles to virtuous - Ingredients for success

- Create your own

EcoTipping Points!

Stories by Region

- USA-Canada

- Latin America

- Europe

- Middle East

- South Asia

- Southeast Asia

- East Asia

- Africa

- Oceania-Australia

Stories by Topic

- Agriculture

- Business

- Education

- Energy

- Fisheries

- Forests

- Public Health

- Urban Ecosystems

- Water and Watersheds

Short Videos

- Saving a Coral Reef and Fishery (Apo Island, Philippines)

- Community Gardens Reverse Urban Decay (NYC, USA)

- Community Forests Reverse Tropical Deforestation (Thailand)

- Escaping the Pesticide Trap (India)

- Rainwater Harvesting and Groundwater Replenishment (Rajasthan, India)

How Success Works:

- Saving a Coral Reef and Fishery (Apo Island, Philippines)

- Community Gardens Reverse Urban Decay (NYC, USA)

- Community Forests Reverse Tropical Deforestation (Thailand)

- Escaping the Pesticide Trap (India)

- Rainwater Harvesting and Groundwater Replenishment (Rajasthan, India)

Human Ecology:

Principles underlying

EcoTipping Points

Stories of Fisheries

In-depth (based on site visits with extensive interviews)

- India – East Calcutta - Making the Most of It: Wastewater, Fishponds, and Agriculture - Municipal wastewater feeds an integrated system of fish ponds and farms.

- Mexico - Quintana Roo - The Vigía Chico Fishing Cooperative - A remote fishing village devises community management to protect its lobster fishery and ensure a high quality of life for everyone

- Philippines - Apo Island - Marine Sanctuary: Restoring a Coral-Reef Fishery - A marine sanctuary rescues a fishery and coral-reef ecosystem headed for collapse.

- USA - Hawaii (Oahu) - He‘eia Fishpond and Watershed - Ecosystem restoration at He‘eia, Hawai‘i spans the watershed from the coastal fishpond to the upper valley.

- USA - Hawaii (Oahu) - EcoTipping Points at Hanauma Bay - An idyllic bay goes through two cycles of overuse and preservation.

- USA - Hawaii (Big Island) - The West Hawai‘i Fisheries Council: A Forum for Coral Reef Stakeholders - Stakeholder dialog reduces conflict and improves management of a coral reef.

Capsule (shorter pieces which appear below)

- Canada - British Columbia - Sustainable Oyster Farming - Oyster farming diversifies the economy and provides incentives for ecological protection.

- Fiji & Cook Islands - Coastal Fishery Restoration - Traditional no-take reserves and seasonal taboos restore troubled coastal fisheries.

- Guam - The Humåtak Project - A community-based project works to restore Guam's watersheds, coral reefs, and fisheries.

- Mexico - Sonora - Seri’s Sustainable Fisheries - The Seri Indians made full use of their traditional territorial rights in the Gulf of California to develop sustainable fisheries and scallop harvesting.

- USA - Community-Supported Fisheries - Modeled after community-supported agriculture, community-supported fisheries benefit fishermen, consumers, and the environment.

- USA – Maine – Alewife Restoration - Extraordinary measures are taken to restore Maine's river herring population, a keystone species in the ecosystem.

- USA - Maine - Maine Lobsters - Co-management in the Maine lobster fishery helps promote sustainability.

- USA - Washington State - Lummi Nation Marine Aquaculture - Native Americans save their reservation with eco-development.

Canada - British Columbia - Sustainable Oyster Farming

- Author: Amanda Suutari

- Posted: May 2005

This case is interesting because it is a radical departure from the boom-bust cycles characterizing Canadian Pacific Coast economies and ecosystems since the early 1900s. These include whaling, sealing, mining, sardine canning, and logging.

Clayoquot Sound includes coastal temperate rainforest, rivers, lakes, marine areas and beaches, and is home of the Nootka first nations peoples. It is best-known as being the focal point of one of the country's largest civil society campaigns to stop industrial logging, culminating in 1993 when the provincial government allowed logging of old-growth forest in the region. Activists organized blockades and other acts of civil disobedience which finally resulted in the region being declared a World Biosphere Reserve in 2000. (However, critics are skeptical of this because "reserve" does not legally protect the resources. Environmentalists insist that the same companies under changed names are using the sanitized euphemism of "conservation-based forestry" to continue industrial logging in a form virtually unchanged, which has lulled people into the belief that the area is protected.)

Anyway, as the economy searches for solutions to wean itself off its past addictions to resource extraction, aquaculture of shellfish began growing in the region since 1985 as a way to diversify the economy. An important difference between farming of shellfish (mainly oyster but also scallops and clams) and what has gone before is that it depends on a pristine marine ecosystem to thrive. It requires fertile water, good currents, and nutrients, including leaf litter from the shore, which means the marine ecosystem is recognized to include the neighboring terrestrial ecosystem. Because they grow in such good conditions, the oysters themselves are said to be of very high quality. In fact, shellfish farms have had to close a few times by law after heavy rainfall when fecal levels in the inlets where they are raised are too high. The practice itself is low-impact and relatively pollution-free (it does have some impacts and must be monitored carefully). The sector is expected to expand by up to three times by 2007.

This is another illustration of how markets can shape long-term preservation of a resource (as in silvofisheries in Malaysia, tree frogs in Peru, agroforestry in China's upper Yangtze watershed) as much as they were incentives for earlier short-sighted use of resources through the same pattern of discovery, exploitation, and depletion. Finally it shows some residents have learned important lessons after watching history repeating itself for a century.

Fiji & Cook Islands - Coastal Fishery Restoration

- Author: Amanda Suutari

- Posted: May 2005

The decline of the region's fishery (especially the kaikoso, a species of clam important to local subsistence and livelihood) was caused by various factors including overfishing, mangrove destruction, reef blasting, night fishing and foreign fishers.

When villagers of the Veratavou region and a local non-governmental organization got together to find solutions to the problem, they created a list of rules; they banned blasting, gill nets, and mangrove cutting around the lagoon, stopped issuing licenses to foreign fishers, and designated "tabu," or no-take, reserves in designated areas in the lagoons.

Results were immediete and dramatic. The kaikoso increased up to three times in the protected areas, there was a spillover effect into non-protected areas, and other vanished species, including a local delicacy, made reappearances. Residents reported up to 35% increased incomes (some of which goes into a collective trust fund for eight villages, which has been invested into electrification projects). Coastlines are expected to be more resilient to cyclones or other natural disturbances. Community cohesion is increased, and interest in science and tradition among young people has also improved.

Services restored/improved: Food/income, storm protection, cultural heritage values/knowledge systems

This case is similar to what happened in Fiji. The Cook Islands in the South Pacific are populated by indigenous Koutu Nui, whose way of life depends on coastal resources, especially the trochus (their shellfish staple source of subsistence and income).

Similar to Fiji, the Raratonga islanders' fishery was on the decline due to overfishing; fishers were going out further to chase increasingly fewer and less diverse species of seafood; trochus harvests were shrinking.

The elders in Raratonga, alarmed, decided to re-introduce the traditional no-take system known as raui. Unlike Fiji, these are temporary reserves which are instituted or lifted according to season, harvests, and other conditions. Bans on net fishing and night fishing were installed. The local churches, strong social centers for the Koutu Nui people, endorsed the program, which helped strengthen the commitment of villagers. Results were equally dramatic: Trochus populations have exploded, diversity of sea life has rebounded, corals have increased. It has given way to other plans, including bringing local schools to study the life in the lagoon.

Services restored/benefits: food/fiber, ornamental resources (trochus shells), recreation and tourism, education

For more information visit the South Pacific Regional Environment Programme.

Guam – The Humåtak Project

- Author: Regina Gregory

- Posted: September 2013

In the 1970s, Fouha (aka Fu’a) Bay on the southwest shore of Guam was home to a healthy coral reef ecosystem teeming with marine life, according to data from the University of Guam. But in 1988-1992 the Agat-Umatac Road was constructed without environmental mitigation measures, and hundreds of tons of sediment washed into the bay. The nearshore corals were smothered and killed, and the reef became dominated by algae instead of coral. Besides this catastrophic event, ongoing soil erosion and sedimentation are caused by ungulates (deer and pigs) and human activities in the watershed—especially the deer hunters’ practice of burning whole hillsides of forest so the tender new sprouts will attract easy-to-see deers. Some hilltops have become “hardpan,” i.e., all the soil has washed off and no plants can grow.

By 2002, fishing had gotten so bad in Fouha Bay that fishermen in the village of Humåtak (aka Umatac) took their concerns to Mayor Tony Quinata. They believed sedimentation was at the root of the problem. The mayor contacted Robert Richmond, then director of the University of Guam’s Marine Laboratory, for assistance. Dr. Richmond confirmed that sediment is the reef’s primary stressor, and any improvement would require better land management in the bay’s 5-km2 watershed. He assembled a team of researchers from the University of Guam Marine Laboratory, the University of Hawai‘i Social Science Research Institute, and the Australian Institute of Marine Science and obtained funding from the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

In cooperation with the mayor’s planning office, the researchers implemented a collaborative watershed planning project to help the people of Humåtak identify problems and solutions. This was the beginning of the Humåtak Project. As a partnership formed between community members, scientists, and resource agencies, the Humåtak Project became a community-led initiative with numerous partner organizations in the government, the university and high schools, and non-governmental organizations. “What we have is a community that is fully engaged in caring for their ecosystem,” says project coordinator Austin Shelton. Shelton is a marine biology Ph.D. student and a research assistant to Dr. Richmond at the University of Hawaii Marine Laboratory. They continue to provide scientific guidance and coordination for the Humåtak Project community restoration effort under a NOAA grant titled “Science to Conservation: Linking coral reefs, coastal watersheds and their human communities in the Pacific Islands."

The Humåtak Project’s objectives are to:

- have islanders develop true concern for the environment and natural resources;

- reduce sedimentation;

- reestablish fertile land and native forest;

- restore the health of the once-vibrant coral reefs and the abundant nearshore fisheries.

The three main components of the project are: educational outreach, watershed management, and scientific research.

Educational Outreach

Several projects are designed to increase environmental awareness in the community. According to the website (http://humatakproject.org/about-us.html):

The ‘Humåtak Project Educational Outreach Team’ delivers environmental education presentations to classrooms, summer camps, and community groups. Presentations focus on the problem of erosion, which leads to the destruction of native forests, loss of fertile land, contamination of drinking water supplies, sedimentation on coral reefs, and loss of the essential fish habitat.

The Humåtak Project also hosts “Watershed Adventure” field trips, taking participants through the watershed and explaining ecosystem connections. The first of these was in November 2012, when 160 participants—mostly high school marine biology students—hiked from the top of the watershed down to the bay and learned about the ecosystem. Half a dozen more Watershed Adventures have been conducted since then.

Community meetings are held at the village community center to update community members on the progress of initiatives. The Humåtak Project also utilizes social media to build environmental awareness and stay in touch with community members and volunteers. (Humåtak Project on Facebook)

Watershed Management

“The reefs further from shore are still OK,” says Shelton, but “the land is moving into the sea. We want to help the coral move back toward the land.” According to Shelton, once the stressor of sediment is removed, the reef can heal itself through natural processes. Sediment is gradually flushed out of the bay and fish will eat the excessive algae.

Beginning in 9011, the Humåtak Project’s erosion control projects include an innovative combination of reforestation and soil stabilization. In addition to planting tree seedlings, sediment filter socks are installed on the slopes of the watershed. The trees are donated by the Guam Department of Agriculture Forestry Division. The filter socks are created by the Humåtak Project itself, by stuffing mesh stockings with mulch and shredded telephone books. The socks are placed across the flow of water. They reduce erosion in three ways: by slowing water runoff; by trapping sediment; and by stabilizing land, allowing vegetation to reclaim bare soil areas. The photos below show how this method is effective in a very short time.

Source: Micronesia Challenge, May 24, 2013

Labor for these efforts comes from volunteers in the community, Americorps workers, and groups such as the University of Guam Green Interns. The project has hundreds of volunteers, who to date have contributed over 1,500 hours of labor.

To discourage arson by deer hunters, the Humåtak Project gives them alternative deer attractants such as salt licks free of charge, through a partnership with the Guam Coastal Management Program.

Scientific Research

The Humåtak Project is fulfilling a need for long-term, comprehensive data. Two of the Humåtak Project’s most important partners are the Guam Coastal Management Program Long-Term Coral Reef Monitoring Program, and the Guam Community Coral Reef Monitoring Program, which diligently monitor the health of the reef--including coral habitat and associated biological communities (reef fishes, sea stars, sea cucumbers, trochus, and other ecologically and economically important reef organisms)--in hopes of seeing improvement.

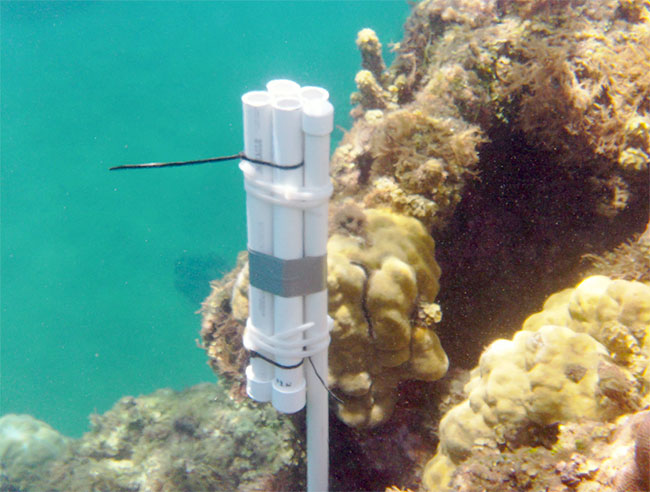

Sedimentation in Fouha Bay is the focus of Austin Shelton’s current research for his Ph.D. in marine biology from the University of Hawai‘i. He has placed sediment traps and multiparameter datasondes throughout the bay to collect data about turbidity, temperature, and salinity. In another year or so the data will be processed and compared to data collected in 2003 and 1978.

Source: Micronesia Challenge, May 24, 2013

The data are expected to be useful in other projects, particularly in improving the science of mitigating for impacts to coral reefs and aquatic resources. Shelton notes that a proposed expansion of the U.S. military on Guam might possibly destroy 70 acres of coral reefs to make way for an aircraft carrier. Federal law requires “compensatory mitigation”—i.e., additional mitigation projects that, together with the proposed project, would result in no net loss of coral reefs. Thus it is important to quantify a correlation between, e.g., the number of trees and filter socks and the acres of coral reefs they might help to rehabilitate.

The Humåtak Project’s slogan is “Reviving Guam, one bay at a time,” and Shelton hopes the model will spread to other watersheds.

Mexico - Sonora - Seri’s Sustainable Fisheries

- Author: David Nuñez

- Posted: May 2009

The Seri or Comcaac are an indigenous people that up to a few decades ago still practiced a semi-nomadic hunter/gatherer lifestyle among the islands of the Gulf of California, in Northwest Mexico. Wars of extermination carried out first by Spaniards, and then by independent Mexico (hostilities did not end until the early 20th Century), took them to the brink of extinction and only about 600 remain today.

In the 1930s the federal government abandoned its extermination and relocation strategy and instead tried to settle the Seri in two villages within their territory, El Desemboque and Punta Chueca, by facilitating the creation of a fishing cooperative. The shark fishery was heavily promoted, particularly for the extraction and processing of livers to yield vitamins. But with the advent of synthetic vitamin production in the 1940s, the fishery collapsed and the Seri turned to hunting sea turtles, which in turn was banned by the 1980s. Meanwhile during the 1970s outsiders discovered a profitable scallop fishery just off-shore which fueled an influx of non-Seri fishermen into the region.

In an effort to correct past wrongs and help the Seri survive, the Mexican government granted the Seri collective ownership of a fraction of their historical range in 1975. This included Isla Tiburon (Shark Island) and the land across from it on the mainland, as well as exclusive fishing rights to the surrounding waters. Unfortunately, the exact limits of these waters were never properly established and a lack of vigilance from authorities has restricted the Seri Exclusive Fishing Zone to the channel between the Island and the Mainland, which is narrow enough to allow the community to control access.

Free from government interference in their affairs, the Seri community has developed a set of rules that has allowed catches within this small channel to remain stable over the past thirty years, while the productivity of much larger neighboring fisheries has collapsed by up to 90%. The successful management of their tiny fishery has now been recognized by their neighbors, and the lessons learned are being used to implement similar programs in neighboring communities.

Though several different species of fish, crustacean and mollusk are harvested in the channel, the scallop fishery offers us a good example of just how the Seri use cultural, social and biological knowledge to effectively manage their fisheries.

Though Seri do participate in the commercial scallop fishery, most are reluctant to dive and so most of the fishing is done by outside crews. To be granted access to the channel, outsiders must 1) pay an entrance fee, 2) hire a Seri as member of the crew at the same wages (not only does this increase employment, but it allows the Seri to monitor the outsiders), 3) avoid fishing in the sandbar areas which are restricted to subsistence fishing mentioned below, and 4) agree to a catch limits.

The subsistence scallop fishery is a traditional activity which takes place during the lowest tides of the year, in which shallow waters allow the scallops to be harvested by women and children, without diving. Historically it has been an important social & cultural event in Seri society, and also serves to monitor the overall health of the fishery. When these harvests are low, social repercussions can be harsh: women might humiliate the men in public for being careless with such a valued common resource, and the men in turn will blame the outsiders and cancel all access until tempers cool, stocks recover or economic necessity forces them to issue permits once again.

The fishermen's deep knowledge of the fishery itself also enhances its sustainability. By capturing only the largest scallops, they increase the likelihood that any animal caught has already reproduced. And by abstaining from diving in seasonal seagrass beds, where the work is harder and one is more likely to step on stingrays and crabs, they ensure that over 10% of the channel is off-limits for at least 8 months a year. Finally, the Seri are well tuned to both the abundance and size of their catch, and rotate fishing grounds regularly, with some sites being visited several times a year, and others only once every few years.

Their success has allowed them to begin sending their children to university, and in 1998 for the first time the younger generation won local elections and a college graduate was elected as their leader. With these changes the Seri have begun cooperating with NGOs and universities, who are trying to replicate their model in other communities. They have become certified by the Marine Stewardship Council, and branched out into other ventures, such as a Women Artisans Cooperative that sells arts and crafts to tourists; and a Sea Turtle Conservation program that has won international awards.

It is obvious that one of Mexico’s smallest minorities has a lot to teach the rest of us.

For further information see Comunidad y Biodiversidad.

USA - Community-Supported Fisheries

- Author: Regina Gregory

- Posted: February 2016

The Current Situation

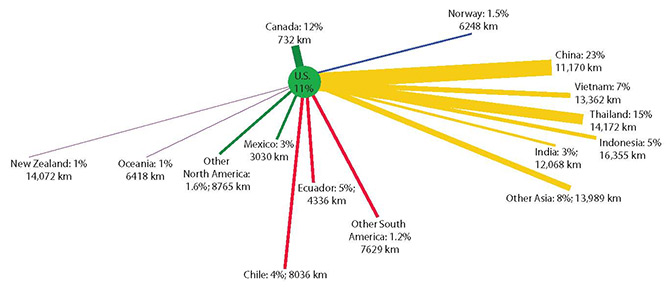

Like nearly everything else in the world, seafood has become part of the industrialized, globalized marketplace. An estimated 80% to 91% of all the seafood consumed in the U.S. is imported (Nextworld n.d., Greenberg 2014, Conniff 2014). Shrimp (mostly farm-raised in Asia) has surpassed tuna and salmon as America’s favorite seafood. One third of the U.S. catch is exported, but much of that makes an “Asian round trip”: it is frozen, shipped overseas, thawed, filleted by low-cost labor, refrozen, and sent back as imports. On the other hand, foreign fish processed in the U.S.—e.g. blocks of imported “white fish” (tilapia and catfish) that are cut into fish sticks and sent overseas—is considered an American export (Greenberg 2014). To make matters even murkier, up to one third of imported seafood is “IUU” fish—illegal, unreported, and unregulated (Conniff 2014).

Figure 1 shows the sources and distance traveled of U.S. seafood imports. The average distance between where a fish is caught and where it is eaten is 8,812 km (5,476 mi) (McClenachan et al. 2014).

Figure 1. U.S. seafood imports

Source: McClenachan et al. 2014

Besides producing stale fish with a very large carbon footprint, this has several negative repercussions:

- The deluge of imported fish (especially IUU fish) depresses the market price that U.S. fishermen are paid for their catch. This affects especially small boats with slim profit margins; many have been forced out of business.

- Imported seafood can be hazardous to your health. Only 1% of it is tested, and of that, about half is rejected because of contaminants such as bacteria and viruses, antibiotics and fungicides. One place in Vietnam was found to be raising fish in sewage (Nextworld n.d.).

- The beloved shrimp has an additional set of problems, including slavery-like conditions for the workforce; destruction of ecologically critical mangroves; and consumption of 1.3 pounds of processed fishmeal from wild sources for every 1 pound of farm-raised shrimp (Philpott 2016).

- The global market makes U.S. citizens less concerned about the ocean environment. “Globalization has radically disconnected us from our seafood supply,” says Greenberg (2014), and “when trade so completely severs us from our coastal ecosystems, what motivation have we to preserve them?” For instance, with so much farmed salmon coming into the country, he says, no one seems concerned that the proposed Pebble Mine in Alaska will ruin the spawning grounds of the largest wild sockeye salmon run on earth.

Alternative: Community-Supported Fisheries

According to the Northwest Atlantic Marine Alliance (NAMA),

It makes no sense to pay fishermen a price that doesn't cover their real cost of operation while the consumers are paying much more than they should for packaged, frozen or days-old seafood trucked hundreds or thousands of miles when it was caught steps away from our homes (namanet.org).

One of NAMA’s “market transformation” strategies has been to promote community-supported fisheries (CSFs). Modeled after community-supported agriculture, a CSF is a community of consumers collaborating with local fishermen to buy fish directly for a predetermined price and length of time. Usually customers pre-pay for a season and receive weekly or bi-weekly allotments of fish (namanet.org, localcatch.org).

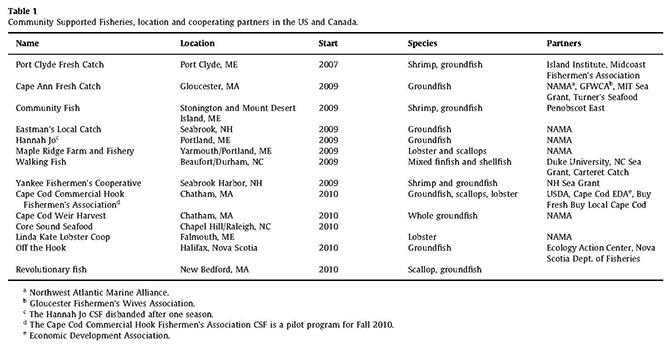

The first CSF appeared in Maine in 2007. Now there are over 30 in the U.S. and Canada, with over 250 distribution locations. There are about 50 CSFs around the world. In 2012 they formed a “community-of-practice” called Local Catch, which includes fisherman, organizers, researchers, and consumers.

While CSFs are all based on the same business model, they are very diverse. Some were created by existing fishermen’s cooperatives; some had the help of government agencies, academic institutions, and non-profit organizations (see Table 1). Some have only a single fisherman and a single boat; some have several dozen. The number of shareholders ranges from 100 to 2,000. Some have dockside pick-up; others have many distribution points around a city or region. Skipper Otto’s on the west coast of Canada even delivers to the inland provinces of Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Ontario. Some sell whole fish and others fillets. Some offer a “basket” of variable seafood depending on what the fishermen catch, while others specialize in specific species. Most are on the coast, but some are inland. One (Maple Ridge Farm and Fishery in Maine) combines community-supported agriculture with community-supported fishing (Brinson et al. 2011, Conniff 2014, McClenachan 2014, skipperotto.com, getrealmaine.com).

Source: Brinson et al. 2011

Steve Parkes of Cape Ann Fresh Catch distributes seafood to shareholders at the Morse School in Cambridge

Source: namanet.org

Like community-supported agriculture, community-supported fisheries shorten the distribution chain considerably, as shown in Figure 2. The average distance a fish travels is 65 km (40 mi) instead of 8,812 km (5,476 mi) (McClenachan et al. 2014).

Figure 2. Conventional vs. community-supported distribution chain for fish

Source: McClenachan et al. 2014

Besides producing fresh fish with a very small carbon footprint, CSFs have many other benefits:

- They improve the price for both fishermen and consumers. Fishermen are paid more than they could get wholesale, and consumers pay less than they would at the supermarket (some as low as $3 per pound). This allows fishermen to make a living while catching fewer fish, which in turn is good for fish stocks.

- Fishermen benefit by receiving necessary resources early in the season, bridging the gap between pre-season expenses and fishing-season income.

- Wasteful bycatch is reduced because CSFs create markets for lesser-known species, including some highly abundant stocks not targeted by industrialized fisheries (McClenachan et al. 2014).

- Most CSFs have a code of conduct for fishermen in which they agree to fish in a sustainable manner, e.g., by catching only what is in season, using lower-impact gear, and dumping no waste.

- CSF shareholders form a political base of support for small fishermen and the ocean environment.

- Local markets increase the economic vitality of coastal communities and maintain working waterfronts.

- The system is transparent. Each fish is traceable from “bait to plate.” This is not just traceability but “faceability” because it gives the person who caught the fish a face, says Jack Kittinger, director of Conservation International Hawai‘i, which recently helped create Hawai‘i’s first CSF, Local I‘a. “It’s seafood with a story and the story highlights the local fishermen who are out there bringing in this seafood” (Navares Myers 2015).

- Knowing your fisherman can lead to rewarding relationships and a greater sense of community.

- The CSF model ensures that independent, small-scale harvesters can continue to fish using the low impact practices their parents and grandparents used before them and still remain in an industry that is rapidly becoming dominated by big business and aquaculture (skipperotto.com).

- CSFs provide hope for the youth that fishing is a career option.

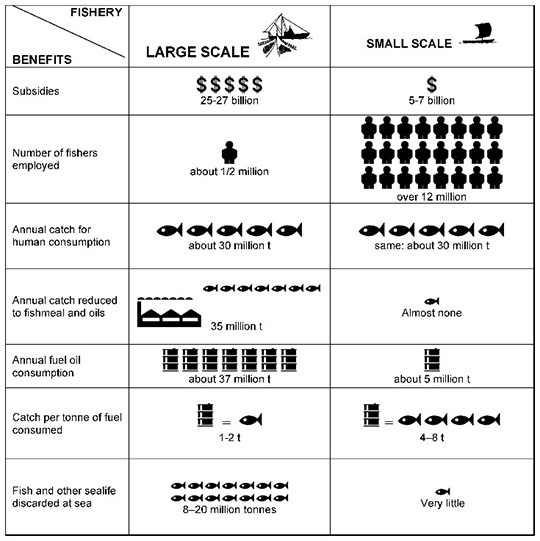

- Keeping small, owner-operated boats afloat at a time when they are increasing being forced out of the market has an additional set of benefits (see Figure 3). With about the same amount of catch for human consumption, small-scale fishing generates much more employment and has much smaller negative impacts than large-scale fishing.

Figure 3. Impacts of large-scale vs. small-scale fishing operations

Source: Chart created by Daniel Pauly posted on namanet.org

Get Involved

To find a CSF in your area, visit Local Catch’s locator at http://www.localcatch.org/locator/. It includes not only CSFs but also dock pick-ups, farmers markets, fishermen’s markets, boat-to-school programs, and others.

If no CSF is nearby, create one! Fishermen and community organizers can use NAMA’s Bait Box which explains in detail how to start a CSF. A number of other resource guides are available as well:

- Market Your Catch website

- Starting and Maintaining Community Supported Fishery (CSF) Programs: A Resource Guide for Fishermen and Fishing Communities

- Fishermen's Direct Marketing Manual

- Final Report of the National Summit on Community Supported Fisheries

Organizations such as NAMA, Sea Grant, and Local Catch can offer assistance as well.

References

Brinson, Ayeisha, Min-Yang Lee, and Barbara Rountree. 2011. Direct marketing strategies: The rise of community supported fishery programs. Marine Policy 35, p. 542-548.

Conniff, Richard. 2014. Hook, Line, and Sustainable: 5 Ways Community-Supported Fisheries Trump Supermarket Seafood. Takepart.com, May 6. http://www.takepart.com/article/2014/05/06/how-put-really-legal-seafood-dinner-plate

Greenberg, Paul. 2014. Why Are We Importing Our Own Fish? New York Times, June 20. http://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/22/opinion/sunday/why-are-we-importing-our-own-fish.html?_r=0

McClenachan, Loren, Benjamin P. Neal, Dalal Al-Abdulrazzak,Taylor Witkin, Kara Fisher, and John N. Kittinger. 2014. Do community supported fisheries (CSFs) improve sustainability? Fisheries Research 157, p. 62-69.

Navares Meyers, Alyssa. 2015. Local I‘a: The freshest catch from your local community-supported fishery. Green Magazine 7(2), p. 16-20. http://greenmagazinehawaii.com/local-ia/

Nextworld. n.d. What about fish? Video. http://www.nextworldtv.com/videos/health-and-wellness/what-about-fish.html

Philpott, Tom. 2016. As If Slavery Weren’t Enough, 6 Other Reasons to Avoid Shrimp. Motherjones.com, Jan. 6. http://www.motherjones.com/tom-philpott/2016/01/six-reasons-think-hard-about-shrimp-craving

USA - Maine - Alewife Restoration

- Author: Regina Gregory

- Posted: July 2013

The alewife (Alosa pseudoharengus) is a member of the river herring family, which also includes shad and blueback herring. These species are anadromous, i.e., they travel upriver to spawn. Alewives are born in freshwater rivers and lakes and make their way to the sea after a few months. At age 3-4 years for males and 4-5 years for females, the alewives return to the place of their birth to spawn a new generation. In Maine, the mass migration upriver occurs in May.

Long ago alewives were plentiful in all the rivers along the U.S. East Coast. They provided a welcome food supply when other food stocks were low. In colonial times, widows and the elderly were entitled to 2 bushels of alewives (about 200 fish) each. These were generally smoked for preservation. Others were layered with salt in barrels and shipped to slaves in the West Indies. During the Depression alewife harvest and processing provided much-needed jobs. Now that refrigeration makes for a much greater variety of preferred seafood, alewives are used more for lobster bait than for human consumption.

Regardless of their use to humans, alewives are crucial to the entire ecosystem—a “keystone species.” Everything eats alewives: economically important bottom fish such as cod, haddock, and halibut; migratory species such as striped bass, bluefish, and tuna; various freshwater species such as bass, trout, salmon, pickerel, pike, and perch; fish-eating birds such as osprey, eagles, herons, gulls, terns, cormorants, and loons; marine mammals such as seals, dolphins, whales, and otters. Minks, foxes, raccoons, skunks, weasels, and turtles are also fond of alewives. Moreover, alewives serve as a “buffer” to protect migrating salmon. By swimming upstream at the same time that juvenile salmon are swimming downstream, adult alewives distract the predators. Fortunately, only 2 in 1,000 alewives must survive to spawn in order for the run to be sustainable.

Over the years from colonial times to the mid-1950s, the progress of industrialization decimated alewife populations, primarily from water pollution and dam construction. In Maine, numerous dams were constructed on all the major rivers, preventing alewives from travelling upriver to their native habitat to spawn.

Awareness and conservation efforts began in the early 1960s. At the U.S. federal level, the National Marine Fisheries Service was created to manage fisheries, and in 1965 the Anadromous Fish Conservation Act was passed. States were encouraged to restore fish populations, and were given resources to do so. The Clean Water Act of 1972 helped with water quality improvements. However, alewife populations remained severely depleted. States from Massachusetts to North Carolina have imposed moratoriums on the harvest of alewives, and the federal government is considering listing alewives as a “threatened species” under the Endangered Species Act. The interstate Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission, under Amendment 2 of the Interstate Fishery Management Plan, decreed that river herring fisheries should be closed in any state that has not developed a sustainability plan.

Due to good management practices Maine escaped this fate. Its river herring runs were deemed sustainable under Amendment 2. The full plan is available online. As of 2012, Maine was the only Atlantic state with an active river herring harvest. Forty Maine municipalities have commercial alewife harvesting rights; 24 of these currently have active alewife fisheries. Each municipality with alewife harvesting rights must submit an annual harvesting plan to the state Department of Marine Resources that includes a 3-days-per-week no-fishing period. (The period was 1 day in the 1960s and was increased to 2 days in 1988 and to 3 days in 1995.)

Maine’s efforts to restore alewives’ access to their traditional habitat has included some extraordinary measures. Dams were removed from three major rivers--two on the Penobscot, one on the Kennebec, and one on the Sebasticook—as well as from many smaller waterways. Elsewhere, fish ladders, lifts, and other bypasses enable the fish to get around dams. On the Union River and Saco River, they are trapped and transported by truck to upstream spawning habitat.

Maine rivers and lakes

Source: geology.com

Alewife populations in the Kennebec and Penobscot Rivers are estimated at several million each. The restored Damariscotta Mills fish ladder on the Damariscotta River has become a major tourist attraction as people come from all over to witness the spectacle of more than 400,000 alewives migrating upstream (see photo).

Alewives at Damariscotta Mills fishway

Photo: Portland Press Herald

In sharp contrast to all these alewife restoration efforts, in 1995 the Maine Legislature enacted legislation to prevent alewives from entering the St. Croix River, which forms part of the U.S.-Canada border—reversing the restoration progress made there during the 1980s. Apparently a group of local fishing guides wrongly accused the alewife of damaging smallmouth bass populations and mounted a successful anti-alewife lobbying effort. The St. Croix alewife population fell from 2.6 million in 1987 to only 1,300 in 2007. In 2008, when new legislation required that access to 2% of the watershed be restored, the population was estimated at 12,000. Fifty organizations on both sides of the U.S.-Canada border requested that the International Joint Commission use its authority to reopen the waterway to alewives. The Conservation Law Foundation filed two lawsuits. Finally, in April 2013, the Maine Legislature reversed itself and passed legislation requiring that dams on the St. Croix be reconfigured or operated in a way that allows the unconstrained passage of river herring. On May 13, 2013 the St. Croix was reopened to river herring. "It's a historic moment," said Rep. Madonna Soctomah, representative of the Passamaquoddy Tribe in the Legislature, who sponsored the bill. "It's a really good day for Maine people and the environment."

It is expected that populations could reach up to 10 million in the St. Croix, and up to 50 million for the state of Maine as a whole.

USA - Maine - Maine Lobsters

- Author: Regina Gregory

- Posted: April 2013

According to the Gulf of Maine Research Institute’s “Lobstering History,”

Long ago, lobsters were so plentiful that Native Americans used them to fertilize their fields and to bait their hooks for fishing. In colonial times, lobsters were considered "poverty food." They were harvested from tidal pools and served to children, to prisoners, and to indentured servants…. some of the servants finally rebelled. They had it put into their contracts that they would not be forced to eat lobster more than three times a week.

Today, Maine lobster is a world-famous delicacy that fetched about $330 million in 2012. The lobster’s continued abundance—a stable supply since 1947—attests to the success of a management system that has evolved over the years.

Lobstering as a trap fishery started in Maine around 1850. The lobstermen eventually formed “harbor gangs,” as anthropologist James Acheson puts it, which established a certain territoriality. They had an informal, often unspoken agreement about who belonged to which community and where each member of the fishing community could lay his traps. In 1975 Acheson wrote, “Although their claims are unrecognized by the state, they are well established and backed by surreptitious violence,” meaning mainly cutting an offender’s trap lines.

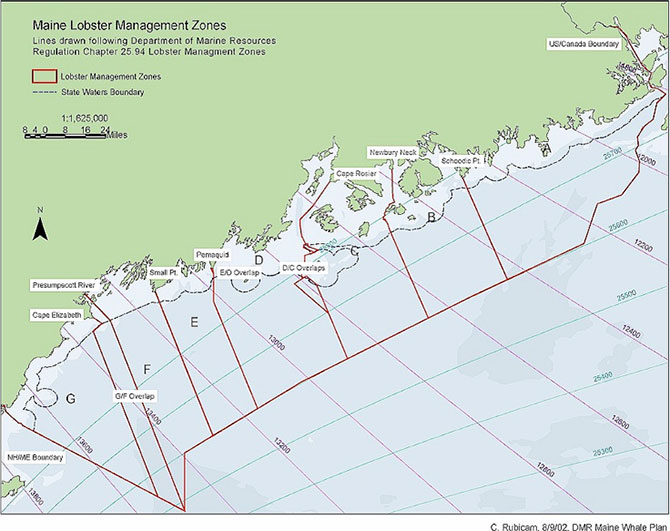

Twenty years later, in 1995, Acheson was able to report that the state had recognized the lobstermen’s claims, as well as their expertise in managing the resource. When Maine’s legislature passed the 1995 Co-Management Law, it divested itself of several contentious issues and allowed the lobstermen themselves to propose the rules of lobster management. Progress was swift: By 1997 seven zones had been established (see map), each with a zone council elected by the licensed lobster fishers in that zone. By 1998 all seven had established progressively decreasing trap limits of 600 to 800 per fisherman by the year 2000, as well as a policy on fishing hours (dates and times of day). The Co-Management Law also included a statewide trap tag identification system and an apprenticeship program.

Source: Maine Department of Marine Resources (http://www.maine.gov/dmr/council/lobsterzonecouncils)

In a system similar to the West Hawaii Fisheries Council (see the EcoTipping Points story), besides establishing zones, the zone councils can propose rules to the state of Maine Department of Marine Resources, which can then adopt them or not. Acheson notes that Maine had a sympathetic Commissioner of Marine Resources who accepted all the recommendations; having someone else in that position might have had a different outcome. For certain specific areas, however, the fishermen have the final say. For instance, the waters around the island of Criehaven “shall be closed or opened to lobster fishing whenever a majority of the lobster fishermen at Criehaven so petition the Commissioner“ (Maine Department of Marine Resources Regulations, Ch. 25.01).

Acheson notes that the trap limits were not popular with the “big fishermen” who would have to reduce their trap numbers, and as a management measure they were not sufficient if entry into the fishery itself is unlimited. So in 1999 the zone councils were given the additional power of suggesting limited entry rules, that is, establishing the ratio of new permits to the number of permits not renewed each year.

While these limits on fishing effort do help protect the sustainability of the lobster fishery, probably more important are state and federal laws governing which lobsters can be caught. According to the Gulf of Maine Research Institute,

- All states and the federal government share a minimum legal size, 3 1/4 inches carapace-length--from the eye socket to the beginning of the tail. A lobster caught at this size weighs about 1 1/4 lb.

- Any egg-bearing females must be released. Some female lobsters are "V-notched," that is, a triangular slice is cut from a tail flipper. This badge of motherhood is meant to keep them off the dinner table and in the breeding pool. Cutting the V-notch is a voluntary action on the part of conservation-minded lobstermen and the Department of Marine Resources. At the other end of the spectrum are lobster harvesters who scrub off the eggs from a female and remove any traces with bleach. Conscientious lobstermen and lobster police do not look kindly on these people.

- Maine imposes a maximum legal size of 5 inches carapace-length so all our biggest breeders, which may produce 100,000 eggs rather than the average 10,000 eggs, can stay in the population.

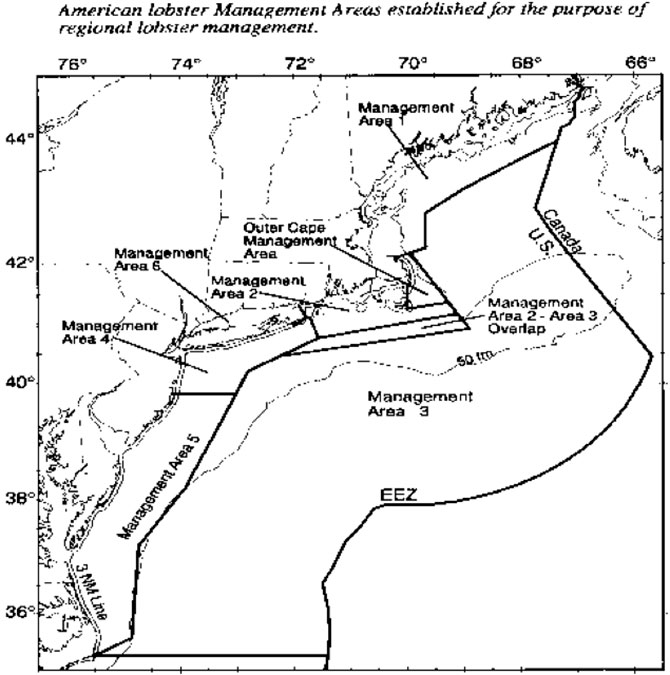

Between the state and federal levels of governance there is an interstate level—the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC) (established 1942). “A compact of 15 eastern seaboard states, the Commission has three representatives from each state. These people include the Director of the state's marine resources management agency, a state legislator, and a fisheries representative appointed by the Governor” (GMRI n.d.). Concerned mainly about improving the rate of recruitment (i.e., new baby lobsters) to avert a population collapse, the Commission pays considerable attention to human impacts on lobsters and their habitat, e.g., from various forms of water pollution. The Commission divided the eastern coastline from Maine to North Carolina into seven zones (see map), each with its own Lobster Conservation Management Team. For Area 1, the Inshore Gulf of Maine, for instance, the ASMFC management plan (ASMFC 1997) specifies trap limits, maximum trap size, maximum lobster size, and stipulates that an area be chosen for complete closure to lobster fishing. The ASMFC fisheries management plan for American lobster is incorporated into Maine’s regulations governing lobster and crab.

The ASMFC can suggest changes to federal regulations, which “may include, but are not limited to, continued reductions of fishing effort or numbers of traps, increases in minimum or decreases in maximum size, increases in the escape vent size, decreases in the lobster trap size, closed areas, closed seasons, landing limits, trip limits and other management area-specific measures” (CFR title 50, § 697.25).

Source: ASMFC 1997

At the federal level, the National Marine Fisheries Service adopts regulations for lobster harvesting in the U.S. exclusive economic zone (EEZ) i.e., 3 to 200 miles from shore. Where federal and state laws are both in force, the more restrictive law applies. The Atlantic Coastal Fisheries Cooperative Management Act (16 U.S.C. 5101 et seq),implemented by the regulations in the Code of Federal Regulations Title 50, Part 697, ATLANTIC COASTAL FISHERIES COOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT, establishes yet another set of zones, with trap limits and permit requirements, etc. for fishing in the EEZ.

Thus, like a system with precincts and districts, “a person declaring any Maine Lobster Management Zone (LMZ A - G) must also declare federal Lobster Management Area 1” (Maine Department of Marine Resources Regulations, Chapter 25.07).

A broader federal law governing fisheries is the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (reauthorized 2007) which established eight Regional Fishery Management Councils around the country. Maine is in the New England Fishery Management Council.

Many people have noticed that Maine’s co-management system fits perfectly Elinor Ostrom’s description of polycentric, nested institutions for governing common-pool resources, and her design principles:

1A. User Boundaries: Clear and locally understood boundaries between legitimate users and nonusers are present.

1B. Resource Boundaries: Clear boundaries that separate a specific common-pool resource from a larger social-ecological system are present.

2A. Congruence with Local Conditions: Appropriation and provision rules are congruent with local social and environmental conditions.

2B. Appropriation and Provision: Appropriation rules are congruent with provision rules; the distribution of costs is proportional to the distribution of benefits.

3. Collective Choice Arrangements: Most individuals affected by a resource regime are authorized to participate in making and modifying its rules.

4A. Monitoring Users: Individuals who are accountable to or are the users monitor the appropriation and provision levels of the users.

4B. Monitoring the Resource: Individuals who are accountable to or are the users monitor the condition of the resource.

5. Graduated Sanctions: Sanctions for rule violations start very low but become stronger if a user repeatedly violates a rule.

6. Conflict Resolution Mechanisms: Rapid, low cost, local arenas exist for resolving conflicts among users or with officials.

7. Minimal Recognition of Rights: The rights of local users to make their own rules are recognized by the government.

8. Nested Enterprises: When a common-pool resource is closely connected to a larger social-ecological system, governance activities are organized in multiple nested layers.

(Ostrom 2010, p. 653)

Besides these principles, Ostrom (2007) notes several “user attributes” of Maine lobster fishers that are important to the success of local management:

- deep roots in their communities, going back many generations

- local leadership

- norms of trustworthiness and reciprocity with those with whom they have close interactions

- effective knowledge about the resource system and resource units they are using

She also notes that the lobster management system takes advantage of the potential organization and governance of social-ecological systems at small to ever-larger spatial scales. But Acheson et al. (2000) complain that the laws “give the federal government a high degree of authority to manage fisheries from the top down. The passage of these laws means that the United States is going in the exact opposite direction it should be going if we wish to develop co-management governance structures” (p. 60).

References

Acheson, James M. 1975. The Lobster Fiefs: Economic and Ecological Effects of Territoriality in the Maine Lobster Industry. Human Ecology 3(3), p. 183-207.

Acheson, James M., Terry Stockwell, and James A. Wilson. 2000. Evolution of the Maine Lobster Co-management Law. Maine Policy Review, Fall, p. 52-62.

Acheson, James M. and Laura Taylor. 2001. The Anatomy of the Maine Lobster Comanagement Law. Society and Natural Resources 14, p. 425-441.

Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC). 1997. Fishery Management Report No. 29: Amendment 3 to the Interstate Fishery Management Plan For American Lobster.

Website http://www.maine.gov/sos/cec/rules/13/188/ch25a3.pdf

Coombs, Monique. 2011. Lobstering and Common Pool Resource Management in Maine. Grassroots Economic Organizing (GEO) Newsletter 2(9).

Website http://geo.coop/node/654

Gulf of Maine Research Institute (GMRI). n.d. Lobstering History.

Website http://www.gma.org/lobsters/allaboutlobsters/lobsterhistory.html

Ostrom, Elinor. 2007. A diagnostic approach for going beyond panaceas. PNAS 104(39), p. 15181-15187.

Ostrom, Elinor. 2010. Beyond Markets and States: Polycentric Governance of Complex Economic Systems. American Economic Review 100, p. 641–672.

USA - Washington State - Lummi Nation Marine Aquaculture

- Author: Amanda Suutari

- Posted: May 2005

The Lummi Nation occupies some 12,500 acres of land and 8,000 acres of Puget Sound tidelands in the Northwest corner of Washington State, about 200 km north of Seattle.

The Lummi people have lived in Northwest Washington for about 12,000 years and there are about 4,000 members of the nation today. Fishing, especially salmon, has been the basis of their culture and survival, with ceremonies and folklore centered around salmon and salmon fishing. According to Lummi legend, a deity known as the Great Salmon Woman tells them that if they only take the salmon they need and protect the spawning areas, the salmon will thrive; this teaching has shaped their relationship with the salmon and its habitat throughout the generations.

The last decade has seen dramatic drops in salmon stocks all over the Pacific Northwest, with two of the four salmon species considered endangered. This has been due to logging of headwater areas, small dams on salmon streams, ground and water pollution from industry and agricultural wetlands, and inappropriate development of wetlands. The Lummi Nation maintains the largest Native American fishing fleet in the Pacific Northwest, and the most extensive fisheries protection program in the region. Many of its highly qualified tribal fisheries technicians and specialists were trained at Lummi Community College or Lummi School of Aquaculture. The fisheries department has an annual budget of 3 million dollars and overseas one of the country's most successful productive salmon hatcheries in the US.

The goals of the program are to sustainably manage fisheries stocks, including protection of salmon spawning habitat, conducting salmon counts in many small river tributaries near Nooksak Basin, monitoring the return and harvest of salmon and increasing production of hatcheries, pursuing new and stricter laws to protect salmon habitat, and launching an aggressive public education campaign to better inform the public of the importance of salmon as a sustainable source of livelihood. It also manages an extensive shellfish hatchery in the Puget Sound tidelands.

The Lummi Nation is also represented on the International Salmon Commission, among whose goals are to regulate activities of offshore driftnet fisheries. It is a model for involvement of indigenous peoples in planning and management of natural resources, both local and internationally, and its traditional values, such as "generational time" (the impact of today's policies on distant future generations) and management practices have great potential to influence fisheries management policy at the state or national level.

The Lummi Nation also has launched a variety of social programs such as a mobilization against drugs, education and youth programs, and a wellness program aimed at improving physical and mental health.

For more informtaion visit the Lummi Indian Nation.